By Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

October 1, 2025

Adenocarcinoma is a type of gallbladder cancer that starts in glandular cells. These cells normally produce bile and line the inner surface of the gallbladder. In adenocarcinoma, the cells grow in an abnormal and uncontrolled way, invading deeper layers of the gallbladder wall and sometimes spreading to nearby lymph nodes or organs.

Symptoms

Gallbladder adenocarcinoma often causes no symptoms in its early stages. When symptoms do appear, they are usually the same as those caused by gallstones. These may include:

-

Pain in the right upper part of the abdomen.

-

Nausea or vomiting.

-

Bloating or indigestion.

-

Yellowing of the skin or eyes (jaundice) occurs if the bile duct becomes blocked.

Many cancers are only discovered by accident when the gallbladder is removed for presumed gallstones.

Causes and risk factors

Most cases of adenocarcinoma develop after years of irritation or injury to the gallbladder lining.

-

Gallstones – Gallstones are the strongest known risk factor for adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Long-standing, large, or multiple stones increase risk.

-

Chronic inflammation – Long-term irritation, such as from primary sclerosing cholangitis. is associated with an increased risk for developing gallbladder cancer.

-

Infections – Long-term Salmonella typhi infection has been linked to gallbladder cancer in some parts of the world.

-

Pancreatobiliary maljunction – A structural abnormality where pancreatic juice flows into the gallbladder, damaging its lining.

-

Genetic factors – Rarely, inherited syndromes such as Lynch syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis.

Histologic subtypes of adenocarcinoma

Histologic subtypes are based on how the tumor cells look under the microscope. This helps pathologists describe the tumor and sometimes provides clues about its behavior.

Biliary type adenocarcinoma

This is the most common subtype. The cancer cells form small, irregular glands (tube-shaped structures). These glands are surrounded by dense scar-like tissue, called desmoplasia, which develops as the body reacts to the tumor. The cells may produce mucin (a jelly-like substance normally found in mucus) or have a foamy appearance. Biliary-type adenocarcinomas resemble pancreatic cancers and often behave in a similar way.

Intestinal type adenocarcinoma

This rare subtype looks like colon cancer under the microscope. The cells are tall and column-shaped, with elongated nuclei (the control centers of the cells). Some of the tumor cells may produce mucin and resemble goblet cells, which are normally found in the intestine. Because it looks so much like colon cancer, pathologists use special tests to make sure the tumor really started in the gallbladder and is not a spread from the colon.

Mucinous adenocarcinoma

In this subtype, more than half of the tumor is made of pools of mucin. The cancer cells “float” in this mucin. These tumors are often large by the time they are discovered and tend to behave more aggressively than biliary-type cancers.

Noncancerous tumors that can give rise to adenocarcinoma

Some gallbladder adenocarcinomas arise from benign (noncancerous) tumors. When this happens, the tumor usually shows both a noncancerous component and an invasive adenocarcinoma.

Adenocarcinoma arising from a mucinous cystic neoplasm

A mucinous cystic neoplasm is a benign tumor made of cysts (fluid-filled spaces) lined by mucin-producing cells. In some cases, areas of adenocarcinoma develop inside or next to the cysts. This means the tumor has transformed from a noncancerous growth into an invasive cancer.

Adenocarcinoma arising from an intracholecystic papillary neoplasm

An intracholecystic papillary neoplasm is a noncancerous growth that projects into the gallbladder as finger-like fronds. Over time, these growths can accumulate additional changes that allow adenocarcinoma to develop within or beneath them.

How is this diagnosis made?

Most gallbladder adenocarcinomas are diagnosed after surgery to remove the gallbladder, often for presumed gallstones. Pathologists make the diagnosis by examining the tissue under a microscope.

Microscopic features

Under the microscope, adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder is made up of abnormal glands or individual cells that have invaded the wall of the gallbladder. Invasion means the cancer cells have broken through the inner lining and are growing into deeper layers such as the lamina propria, muscle, or fibrous tissue around the muscle. The surrounding tissue often reacts by forming dense scar-like tissue, called desmoplasia. The cancer cells usually have enlarged, irregular nuclei, and pathologists may see mitoses, which are cells caught in the act of dividing. Areas of necrosis, or dead tumor cells caused by rapid growth, may also be present. In many cases, the background gallbladder tissue shows long-term changes such as chronic cholecystitis, metaplasia (replacement of one mature cell type with another), or dysplasia (abnormal but noninvasive cells).

Depth of invasion

The depth of invasion describes how far the cancer cells have grown into the wall of the gallbladder. The gallbladder wall is made up of several layers:

-

Epithelium – The thin inner lining where adenocarcinoma begins.

-

Lamina propria – A thin layer of connective tissue just under the lining.

-

Muscle layer (muscularis) – Helps the gallbladder contract.

-

Perimuscular connective tissue – A fibrous layer outside the muscle.

-

Serosa – The outer covering of the gallbladder, which may be next to the liver or the abdominal cavity.

Pathologists carefully examine which of these layers are invaded by the tumor.

-

T1a – Invasion into the lamina propria only.

-

T1b – Invasion into the muscle layer.

-

T2 – Invasion into the perimuscular connective tissue but not through the outer surface.

-

T3 – Tumor extends through the outer surface or into the liver or one nearby organ.

-

T4 – Tumor invades major blood vessels of the liver or multiple nearby organs.

The deeper the invasion, the more serious the cancer and the greater the risk that it has spread. Depth of invasion is one of the most important features in staging and prognosis.

Additional tests that may be used

Pathologists sometimes order extra tests to confirm the diagnosis, rule out spread from another organ, or identify treatment options.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) uses antibodies to detect proteins inside the tumor cells. Gallbladder adenocarcinomas are usually positive for cytokeratin 7, while tumors that spread from the colon are often positive for cytokeratin 20, CDX2, or SATB2.

HER2 (ERBB2) testing

Some adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder show amplification of the HER2 gene or overproduction of the HER2 protein. This can make the tumor eligible for targeted therapy with anti-HER2 drugs.

Mismatch repair protein testing

Mismatch repair proteins fix errors in DNA. If these proteins are missing, the tumor shows microsatellite instability (MSI). MSI can make the cancer more likely to respond to immunotherapy.

Molecular testing

Molecular tests can look for changes in genes such as TP53, CDKN2A, ARID1A, PIK3CA, CTNNB1, and KRAS. These changes are common in gallbladder cancer and may be important for future clinical trials.

Grade

Grade describes how much the cancer cells look like normal cells.

-

Well differentiated (low grade) – The tumor makes many glands that resemble normal tissue.

-

Moderately differentiated (intermediate grade) – The tumor makes fewer glands, and the cells look more abnormal.

-

Poorly differentiated (high grade) – The tumor makes very few glands, and the cells grow in solid sheets or as scattered single cells.

High-grade tumors are more aggressive and more likely to spread. Grade is important because it helps doctors predict how the cancer may behave and which treatments may be needed.

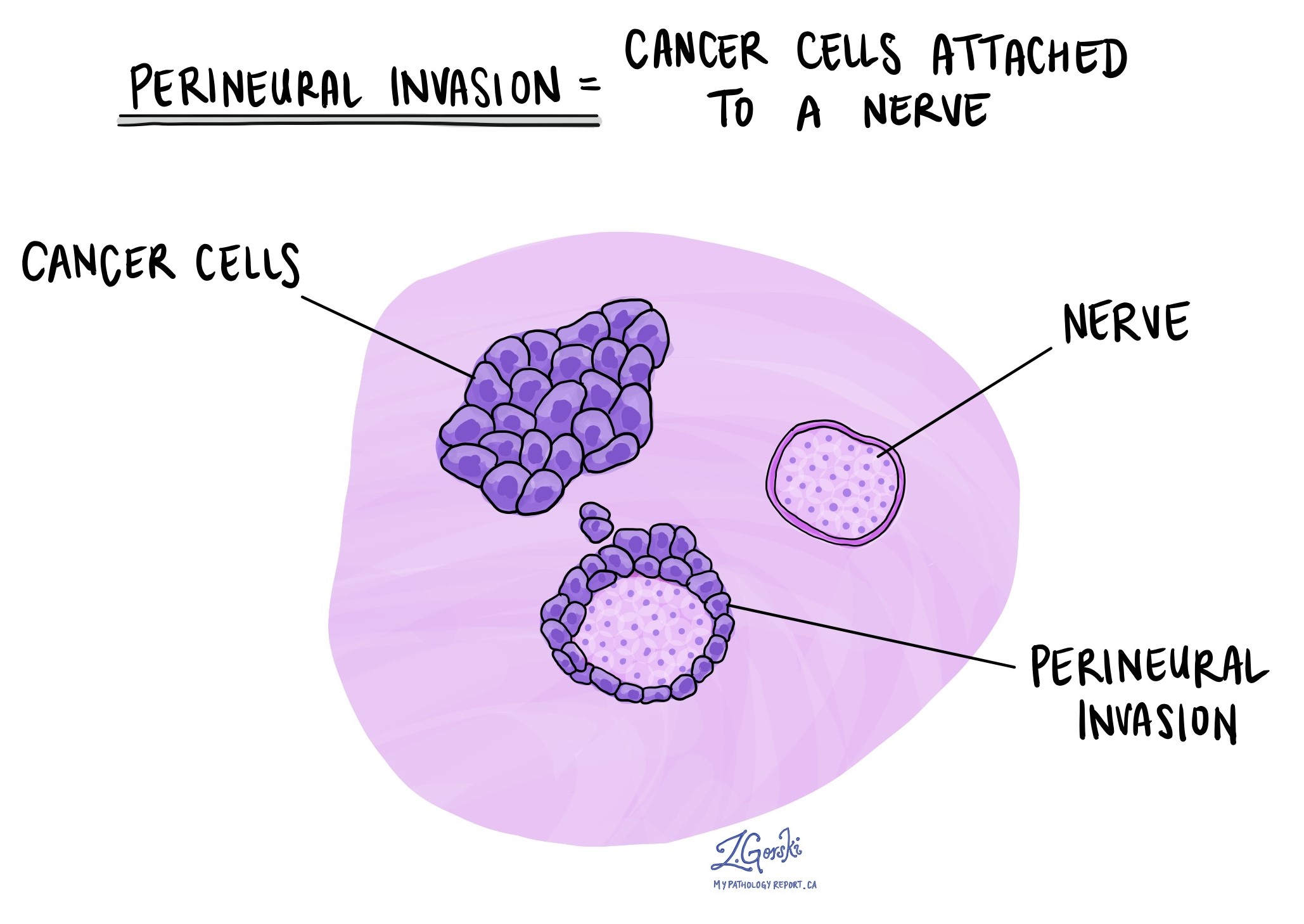

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion (PNI) means cancer cells are seen growing along or around nerves. Because nerves connect different parts of the body, this finding increases the risk of the cancer spreading locally and recurring after treatment.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means cancer cells are seen inside small blood vessels or lymphatic channels. This provides a pathway for the cancer to spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body. Finding lymphovascular invasion is linked to a higher chance of recurrence.

Margins

A margin is the cut edge of tissue removed during surgery. Pathologists carefully examine all margins to see if cancer cells are present.

-

Cystic duct margin – The cut edge where the gallbladder joins the bile duct.

-

Liver bed (hepatic) margin – The cut edge where the gallbladder attaches to the liver.

-

Other soft tissue margins – Depending on the surgery, these may include surrounding connective tissue or vascular structures.

A negative margin means no cancer is at the edge. A positive margin means cancer cells reach the edge, which increases the risk of the tumor returning at that site.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs that filter lymph fluid and can trap cancer cells. They are often removed and examined during gallbladder surgery because cancer can spread to them early.

Pathologists report:

-

The total number of lymph nodes examined

-

The number of lymph nodes that contain cancer

-

The location of any positive nodes

This information is used to assign the N stage:

-

N0 – No cancer found in lymph nodes.

-

N1 – Cancer found in lymph nodes close to the gallbladder (for example, nodes near the cystic duct, common bile duct, or hepatic artery).

-

N2 – Cancer found in more distant regional lymph nodes (for example, nodes along the aorta or in the retroperitoneum).

Cancer in lymph nodes increases the stage of disease and is linked to a higher chance of recurrence.

Staging

Staging describes how far the cancer has spread. It combines information from the T (tumor), N (nodes), and M (metastasis) categories.

-

Tis – Cancer cells remain only in the inner lining (carcinoma in situ).

-

T1a – Cancer invades the lamina propria.

-

T1b – Cancer invades the muscle layer.

-

T2 – Cancer invades the perimuscular connective tissue but not through the outer surface. May be described as T2a (toward the abdominal cavity side) or T2b (toward the liver side).

-

T3 – Cancer grows through the outer surface or into the liver or one nearby organ.

-

T4 – Cancer invades major blood vessels of the liver or multiple nearby organs.

-

N0 – No lymph node involvement.

-

N1 – Cancer in nearby lymph nodes.

-

N2 – Cancer in more distant regional nodes.

The pathologic stage (pTNM) is determined by combining these categories. For example, a tumor that invades the perimuscular connective tissue (T2), with no lymph node involvement (N0) and no metastasis (M0), is stage II.

Prognosis

Prognosis after the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder depends on how advanced the cancer is when it is found and whether it was completely removed.

-

Early cancers (Tis, T1, or very limited T2) that are completely removed are often curable.

-

Deeper invasion into the liver or nearby organs is linked to worse outcomes.

-

Positive margins, lymph node involvement, perineural invasion, or lymphovascular invasion increase the risk of recurrence.

-

For T2 cancers, tumors that grow toward the peritoneal surface (T2a) often have a better outcome than those growing toward the liver (T2b).

Long-term survival is possible if the tumor is discovered early, but most gallbladder adenocarcinomas are found at an advanced stage. In these cases, treatment focuses on controlling the disease and extending survival.

Targeted therapy (HER2-positive tumors) or immunotherapy (tumors with microsatellite instability) may offer additional options in selected cases.

Questions to ask your doctor

- How deep did the cancer invade into the gallbladder wall?

-

Were cancer cells found in my lymph nodes, and what was the N stage?

-

Did the tumor show perineural invasion or lymphovascular invasion?

-

Were the surgical margins negative or positive for cancer cells?

-

What is the grade of my tumor, and how does that affect my prognosis?

-

Do my test results (HER2, mismatch repair, molecular studies) open up any treatment options?

-

What is the overall stage of my cancer?

-

Based on these results, what treatments or follow-up care do you recommend?