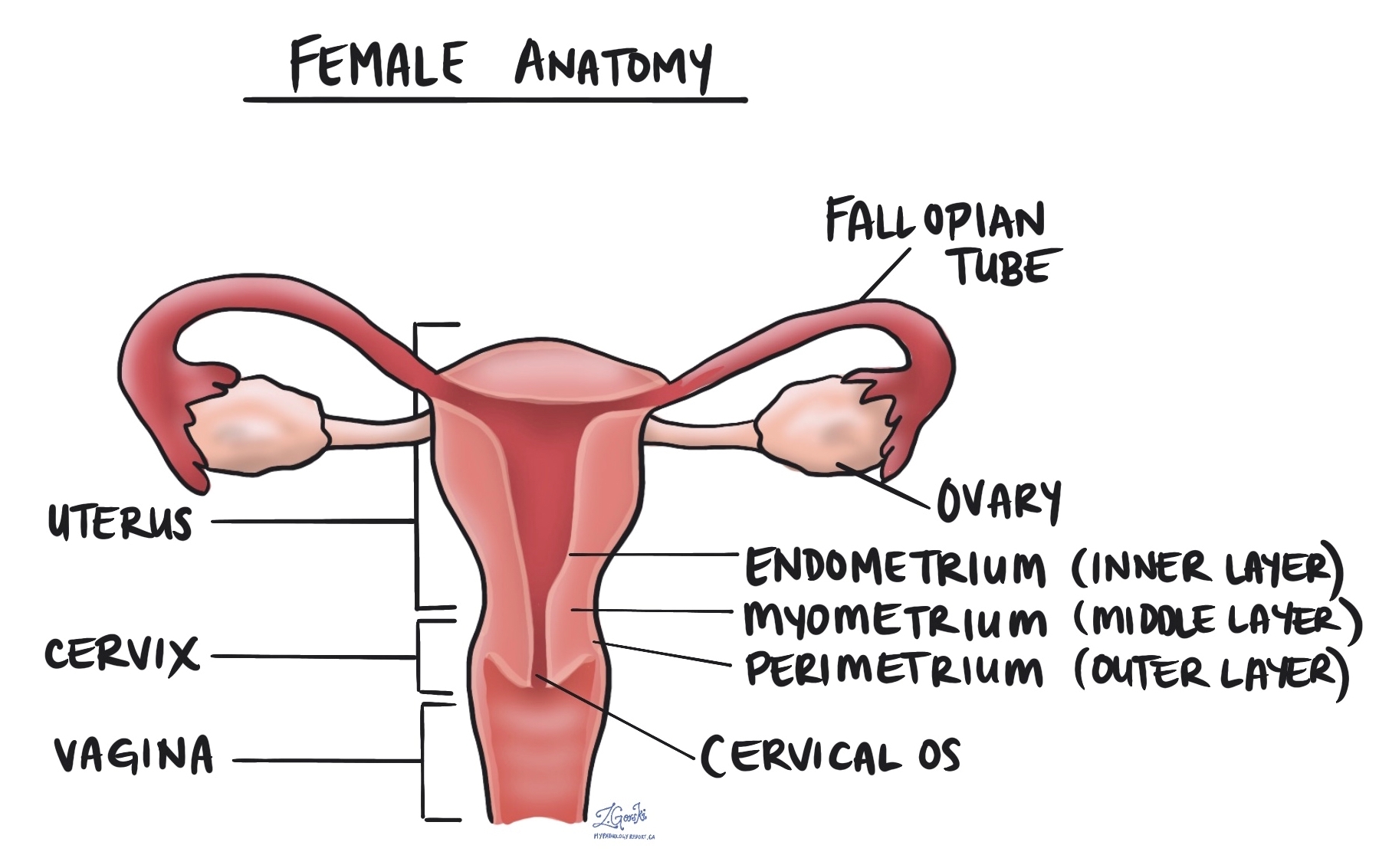

Endometrial glands are tiny tube-shaped structures that make up part of the endometrium, which is the inner lining of the uterus. These glands are made of epithelial cells that produce mucus and other fluids to help prepare the uterus for pregnancy. The spaces between the glands are filled with a supporting tissue called the stroma, which contains blood vessels and immune cells.

What is the function of endometrial glands?

The main job of endometrial glands is to produce secretions that nourish and protect an early embryo and to help create the right environment for a fertilized egg to implant in the uterus.

The activity of the glands changes throughout the menstrual cycle:

-

During the proliferative phase (the first half of the cycle), the glands grow and lengthen under the influence of estrogen.

-

After ovulation, during the secretory phase, the glands become wider and start to produce and release nutrients under the influence of progesterone.

-

If pregnancy does not occur, hormone levels drop, the glands stop secreting, and the upper layer of the endometrium is shed during menstruation.

What do endometrial glands look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, endometrial glands appear as rounded or elongated spaces lined by a single layer of epithelial cells. The appearance of the glands changes depending on the stage of the menstrual cycle:

-

Proliferative phase: The glands are narrow, straight, and closely packed, with cells that have small, uniform nuclei.

-

Secretory phase: The glands become wider and more coiled. The cells contain clear material (glycogen and mucus) that they release into the gland to nourish a possible embryo.

-

Menstrual phase: The glands break down and are shed along with the surrounding tissue and blood.

What conditions affect endometrial glands?

Many uterine conditions involve changes in the number, size, or appearance of endometrial glands.

Common examples include:

-

Endometrial hyperplasia: The glands become crowded and more numerous, making the endometrium thicker than usual.

-

Endometrial polyp: A small, localized overgrowth of glands and stroma forms a polyp that may cause bleeding.

-

Endometrial carcinoma: The gland cells become cancerous, showing abnormal (atypical) features and uncontrolled growth.

-

Atrophic endometrium: After menopause, the glands become small and inactive because of low hormone levels.

Pathologists evaluate the glands’ shape, size, and cellular appearance to determine whether the changes are normal, hormone-related, or caused by disease.

Why are endometrial glands important in a pathology report?

Pathologists often mention endometrial glands when describing biopsy results because the appearance of the glands provides important clues about hormone balance, menstrual cycle phase, and abnormal growth patterns.

For example, finding crowded glands without atypia supports a diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, while crowded glands with atypia suggests a precancerous condition such as atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia.

Understanding how the glands look and behave helps doctors identify the cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and choose the best treatment.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What did the report say about my endometrial glands?

-

Are the glands normal for my age and menstrual cycle?

-

Did the report mention hyperplasia or atypia?

-

What do these findings mean for my hormone levels or risk of cancer?

-

Will I need additional testing or follow-up?