by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

February 5, 2025

Endometrial clear cell carcinoma is a rare but aggressive type of cancer that starts in the lining of the uterus, called the endometrium. The cancer cells in this type of tumour often look clear under the microscope, which is why it is called “clear cell carcinoma.”

Endometrial clear cell carcinoma is considered a high grade tumour, meaning it has a higher chance of spreading beyond the uterus compared to other types of endometrial cancer. Because of this, early diagnosis and treatment are important.

What are the symptoms of endometrial clear cell carcinoma?

The symptoms of endometrial clear cell carcinoma are similar to those of other types of endometrial cancer.

Common symptoms include:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, especially after menopause.

- Heavy or irregular periods in premenopausal individuals.

- Vaginal discharge that may be watery, pink, or brown.

- Pelvic pain or pressure.

- Pain during sexual intercourse.

- Unexplained weight loss or fatigue in advanced cases.

Since abnormal vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom, it is important to see a doctor if you experience any unexpected bleeding, particularly after menopause.

What causes endometrial clear cell carcinoma?

Although the exact cause of endometrial clear cell carcinoma is not fully understood, it is believed to develop due to genetic changes in the cells lining the uterus. Unlike the more common types of endometrial cancer, which are often linked to excess estrogen, clear cell carcinoma is less influenced by hormones.

Risk factors for developing this cancer include:

- Older age, especially postmenopausal women.

- A history of endometrial hyperplasia (abnormal thickening of the endometrial lining).

- Previous pelvic radiation therapy.

- Lynch syndrome or other inherited genetic conditions that increase cancer risk.

- A history of ovarian or breast cancer.

- African American race, as studies suggest a slightly higher risk in this population.

Although these risk factors may increase the likelihood of developing endometrial clear cell carcinoma, some people develop the cancer without any known risk factors.

How is this diagnosis made?

Endometrial clear cell carcinoma is usually diagnosed through a combination of tests, including:

- Pelvic ultrasound: A doctor may perform an ultrasound to look for abnormalities in the uterus.

- Endometrial biopsy: A small tissue sample called a biopsy is taken from the endometrium and examined under a microscope.

- Dilation and curettage (D&C): If the biopsy does not provide enough information, a D&C may be performed to collect a larger tissue sample.

- Hysteroscopy: A thin camera is inserted into the uterus to examine the lining and take tissue samples if needed.

- Pathology examination: A pathologist studies the tissue sample to confirm the diagnosis and look for specific microscopic features that distinguish clear cell carcinoma from other types of endometrial cancer.

If cancer is found, additional tests such as CT scans or MRI may be done to check if the cancer has spread beyond the uterus.

What are the microscopic features of this tumour?

Under the microscope, endometrial clear cell carcinoma has three main growth patterns that may be seen in the same tumour:

- Papillary pattern: The cancer cells grow in small, finger-like projections. These projections often have a thickened, scar-like core.

- Tubulocystic pattern: The tumour forms gland-like spaces and small cysts.

- Solid pattern: The cancer cells grow in sheets without forming glands or cysts.

The individual cancer cells can appear in different shapes, including cuboidal (square), polygonal (many-sided), hobnail (cells with a “bulging” appearance), or flat. Their cytoplasm (the fluid inside the cells) may be clear or pink.

Unlike some other types of endometrial cancer, this type does not show squamous differentiation (when cells take on characteristics of squamous cells). The nuclei (the central part of the cell that contains genetic material) often appear irregular, large, and dark, though their appearance can vary within the same tumour.

The number of mitotic figures (dividing cancer cells) can also vary. However, most tumours have fewer than five mitotic figures per 2 square millimetres of tissue, meaning that the tumour cells divide slower than some other aggressive cancers.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry is a special laboratory test that helps pathologists identify cancer cells by detecting proteins inside them. This test uses special dyes that attach to certain proteins, allowing pathologists to determine whether a tumour has specific molecular features.

For endometrial clear cell carcinoma, the following immunohistochemical markers are often used:

- HNF1β (Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1-beta): Found in 67–100% of clear cell carcinomas.

- Napsin A: Found in 56–93% of cases and helps distinguish clear cell carcinoma from other types of endometrial cancer.

- AMACR (P504S): Found in 75–88% of cases.

- ER (estrogen receptor) and PR (progesterone receptor): Usually negative or only weakly positive, meaning this tumour is not driven by hormones like some other endometrial cancers.

- p53 (tumour suppressor protein): This protein shows abnormal staining patterns in 22–72% of cases, suggesting genetic mutations in this tumour.

These tests help confirm the diagnosis and distinguish clear cell carcinoma from other types of endometrial cancer, such as serous carcinoma or endometrioid carcinoma.

Molecular markers

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) may be performed to look for genetic changes in endometrial clear cell carcinoma. This test examines multiple genes at once to identify mutations that may affect prognosis or guide treatment decisions. However, next-generation sequencing is not performed in all cases, and the genes assessed may vary depending on the institution.

CTNNB1

Mutations in CTNNB1 are found in some endometrial cancers but are rare in clear cell carcinoma. When present, they may indicate an unusual subtype. The result is typically reported as mutated or wild-type (normal).

KRAS

KRAS mutations occur in a subset of endometrial clear cell carcinomas and may be linked to more aggressive tumour behaviour. A KRAS mutation suggests that the cancer cells are growing and dividing more rapidly.

PIK3CA

PIK3CA is involved in cell growth and survival. Mutations in PIK3CA are found in some endometrial clear cell carcinomas and may influence how the tumour responds to specific targeted therapies.

POLE

Mutations in POLE are uncommon in endometrial clear cell carcinoma. When present, they are associated with a better prognosis and a lower risk of recurrence.

PTEN

PTEN is a tumour suppressor gene that helps regulate cell growth. Mutations in PTEN are more common in endometrial endometrioid carcinoma but can also be found in some cases of clear cell carcinoma.

p53

Mutations in p53 are found in a significant proportion of endometrial clear cell carcinomas. An abnormal p53 result suggests a more aggressive tumour, and these tumours are often treated similarly to serous carcinoma.

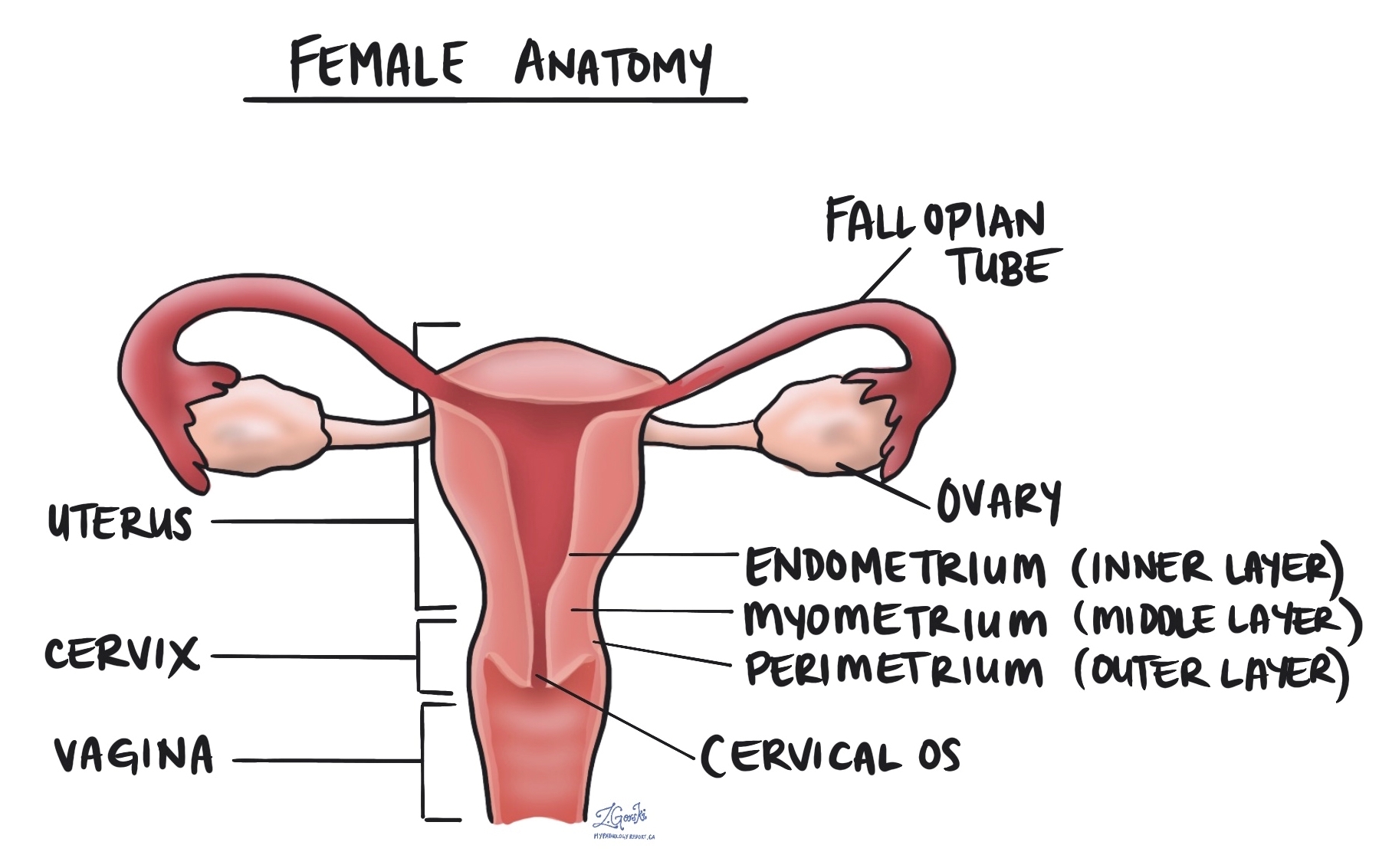

Myometrial invasion

The myometrium is the thick muscular layer of the uterus. Myometrial invasion occurs when the cancer spreads from the inner lining of the uterus (the endometrium) into the myometrium. The depth of myometrial invasion is important because the more deeply the tumour invades, the higher the risk of spreading to other body parts.

Most pathology reports for endometrial clear cell carcinoma will describe the amount of myometrial invasion in millimetres and as a percentage of the total myometrial thickness. This information is used to stage the tumour and to plan treatment.

Cervical stromal invasion

Cervical stromal invasion means that the cancer has spread from the body of the uterus into the cervix, which is the lower part of the uterus that connects to the vagina. This type of invasion indicates a more advanced stage of cancer and may influence treatment decisions, such as the need for more extensive surgery or radiation therapy.

Invasion of surrounding organs or tissues

The uterus is closely connected to several other organs and tissues, such as the ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina, bladder, and rectum. The term “adnexa” refers to the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and ligaments directly linked to the uterus. A tumour can spread into any of these organs or tissues as it grows. In such cases, some parts of these organs or tissues may have to be removed along with the uterus. A pathologist will thoroughly examine these organs or tissues for tumour cells, and the findings will be detailed in your pathology report. The presence of tumour cells in other organs or tissues is significant, as it raises the pathologic tumour stage and is linked with a poorer prognosis.

Lymphatic and vascular invasion

Lymphatic invasion occurs when cancer cells enter the lymphatic system, a network of vessels that helps fight infection. Vascular invasion refers to cancer cells entering the blood vessels. Both lymphatic and vascular invasion are important because they indicate that the cancer is more likely to spread (metastasize) to other body parts, including lymph nodes and distant organs. These findings are often included in a pathology report to help guide treatment decisions.

Margins

A margin refers to the edge of the tissue removed during surgery, such as a hysterectomy. After the surgery, pathologists examine the margins of the tissue under a microscope to check for any remaining cancer cells. In the case of endometrial clear cell carcinoma, several specific margins are carefully evaluated:

- Cervical margin: This is the edge where the uterus meets the cervix. Pathologists examine this margin to see if the cancer has spread into or beyond the cervix.

- Vaginal cuff margin: If the top portion of the vagina is removed along with the uterus, the pathologist will check the vaginal cuff margin to ensure no cancer cells are present at the surgical edge.

- Parametrial margin: This margin includes the tissue around the uterus, including ligaments and connective tissue. It is examined to see if cancer has spread into these areas.

- Peritoneal margin: If the peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity) is removed, it will be examined to check for cancer cells in this area.

If any of these margins contain cancer cells, it is referred to as a positive margin, which may mean some tumour cells were left behind after surgery. A negative margin means no cancer cells were found at the edges, suggesting the tumour was removed entirely. Clear margins are important for reducing the risk of the cancer returning, and positive margins may lead to recommendations for additional treatments, such as radiation therapy.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped structures that are part of the lymphatic system, which helps fight infection and remove waste from the body. Lymph nodes contain immune cells that filter lymph fluid, which travels through lymphatic vessels and helps trap harmful substances like bacteria or cancer cells. Lymph nodes are located throughout the body, including the pelvis and abdomen, close to the uterus.

In the context of endometrial clear cell carcinoma, lymph nodes are examined because this type of cancer has a higher risk of spreading beyond the uterus, particularly to nearby lymph nodes. For this reason, your surgeon may remove lymph nodes from the pelvis or abdomen, which are then sent to the pathologist for examination under a microscope. This is done to check for the presence of metastatic cancer (cancer that has spread from the primary tumour to other areas of the body).

Examining lymph nodes is important for several reasons:

- Determining the cancer stage: If cancer cells are found in the lymph nodes, it indicates that the cancer has spread beyond the uterus, which may place the cancer in a more advanced stage.

- Guiding treatment decisions: The presence of cancer in the lymph nodes can affect treatment options. Patients with lymph node involvement may require more aggressive treatments, such as radiation therapy or chemotherapy, to reduce the risk of recurrence.

- Assessing prognosis: Lymph node involvement is associated with a higher risk of the cancer returning or spreading to other parts of the body. Knowing whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes helps doctors provide more accurate information about the patient’s prognosis.

Isolated tumour cells (ITCs)

Pathologists use the term ‘isolated tumour cells’ to describe a group of tumour cells that measure 0.2 mm or less and are found in a lymph node. If isolated tumour cells are found in all the lymph nodes examined, the pathologic nodal stage is pN1mi.

Micrometastasis

A ‘micrometastasis’ is a group of tumour cells measuring 0.2 mm to 2 mm in a lymph node. If only micrometastases are found in all the lymph nodes examined, the pathologic nodal stage is pN1mi.

Macrometastasis

A ‘macrometastasis’ is a group of tumour cells measuring more than 2 mm and found in a lymph node. Macrometastases are associated with a worse prognosis and may require additional treatment.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

The pathologic stage for endometrial clear cell carcinoma is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT) for endometrial clear cell carcinoma

Endometrial clear cell carcinoma is given a tumour stage between T1 and T4 based on the depth of myometrial invasion and growth of the tumour outside of the uterus.

- T1 – The tumour only involves the uterus.

- T2 – The tumour has grown to involve the cervical stroma.

- T3 – The tumour has grown through the wall of the uterus and is now on the outer surface of the uterus, OR it has grown to involve the fallopian tubes or ovaries.

- T4 – The tumour has grown directly into the bladder or the colon.

Nodal stage (pN) for endometrial clear cell carcinoma

Based on the examination of lymph nodes from the pelvis and abdomen, endometrial clear cell carcinoma is given a nodal stage from N0 to N2.

- N0 – No tumour cells were found in any lymph nodes examined.

- N1mi – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node from the pelvis, but the area with cancer cells was not larger than 2 millimetres (only isolated cancer cells or micrometastasis).

- N1a – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node from the pelvis, and the area with cancer cells was greater than 2 millimetres (macrometastasis).

- N2mi – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node outside the pelvis, but the area with cancer cells was not larger than 2 millimetres (only isolated cancer cells or micrometastasis).

- N2a – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node outside the pelvis, and the area with cancer cells was greater than 2 millimetres (macrometastasis).

- NX – No lymph nodes were sent for examination.

FIGO stage

The FIGO staging system, developed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, is a standardized way of classifying endometrial cancers based on their extent of spread. This system is important because it helps doctors determine the extent of the cancer, plan appropriate treatment, and estimate the prognosis (the likely disease outcome).

- Stage I: The cancer is confined to the uterus.

- IA: The cancer is limited to the endometrium or has invaded less than halfway into the myometrium. Stage IA cancers have an excellent prognosis, with a high likelihood of being successfully treated through surgery alone.

- IB: The cancer has invaded more than halfway into the myometrium. Although Stage IB is more advanced than Stage IA, it generally has a good prognosis, especially if treated promptly.

- Stage II: The cancer has spread from the uterus to the cervix but has not gone beyond the uterus. Stage II cancers are more likely to require additional treatments, such as radiation or chemotherapy, but many patients still have a favourable outcome with appropriate treatment.

- Stage III: The cancer has spread beyond the uterus but is still within the pelvis. Stage III cancers are more advanced and often require a combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. The prognosis is more guarded, but treatment can still be effective in many cases.

- IIIA: The cancer has spread to the outer surface of the uterus or to nearby tissues.

- IIIB: The cancer has spread to the vagina or the pelvic wall.

- IIIC: The cancer has spread to lymph nodes.

- Stage IV: The cancer has spread to distant organs, such as the bladder, bowel, or lungs. Stage IV cancers are the most advanced and carry a more serious prognosis. Treatment at this stage is usually focused on managing symptoms and slowing the progression of the disease.

- IVA: The cancer has spread to nearby organs such as the bladder or rectum.

- IVB: The cancer has spread to distant organs, such as the lungs or liver.

What is the prognosis for a person diagnosed with endometrial clear cell carcinoma?

The prognosis for endometrial clear cell carcinoma depends on several factors, including the stage of the cancer at the time of diagnosis, the size of the tumour, and whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes or distant organs.

The overall five-year survival rate for people with endometrial clear cell carcinoma is between 55% and 78%. However, survival is much higher for early-stage cancers that are limited to the uterus and much lower for advanced cancers that have spread beyond the pelvis.

Because clear cell carcinoma is considered an aggressive cancer, treatment often includes surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Some patients may also receive targeted therapies based on the tumour’s molecular profile.