by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

January 5, 2025

Invasive lobular carcinoma is a type of breast cancer that commonly starts from a non-cancerous growth of abnormal breast cells called lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). LCIS can be present for months or years before turning into invasive lobular carcinoma. Patients with a previous diagnosis of LCIS are at a higher risk of developing it.

What are the symptoms of invasive lobular carcinoma?

The symptoms of invasive lobular carcinoma vary depending on the stage of the disease. Early stages may not cause noticeable symptoms. As the tumour grows, a person may feel a lump in the breast or notice thickening of the breast tissue. Other possible symptoms include changes in the size or shape of the breast, dimpling of the skin, or nipple inversion. Rarely, there may be discharge from the nipple. Sometimes, invasive lobular carcinoma is discovered on imaging tests like a mammogram or ultrasound before symptoms develop.

What causes invasive lobular carcinoma?

Invasive lobular carcinoma develops due to a combination of lifestyle, hormonal, and genetic factors. Some individuals inherit genetic mutations that increase their risk of developing this type of cancer. For example, mutations in the CDH1 gene are linked to both hereditary diffuse gastric cancer and invasive lobular carcinoma. Individuals with this mutation may have up to a 42% lifetime risk of developing invasive lobular carcinoma.

What genetic changes are found in invasive lobular carcinoma?

Most invasive lobular carcinomas show specific genetic and molecular changes. Nearly all tumours express estrogen and progesterone receptors, which help the cancer grow in response to hormones. In contrast, these tumours usually do not show HER2 gene amplification, a feature seen in other breast cancer types.

A key feature of invasive lobular carcinoma is the loss of a protein called E-cadherin, which helps cells stick together. This loss is often caused by mutations in the CDH1 gene. Without E-cadherin, the tumour cells lose their cohesion, leading to the unique growth pattern of invasive lobular carcinoma. Other genetic changes frequently seen include mutations in genes like PIK3CA, PTEN, and RUNX1, as well as alterations in ERBB2 (HER2) and ERBB3. These genetic changes can influence the behaviour of the tumour and its response to treatments.

In rare cases, invasive lobular carcinoma may display mutations linked to a higher risk of recurrence or early relapse, such as mutations in AKT1 or HER2. These findings may guide treatment decisions, including the use of HER2-targeted therapies.

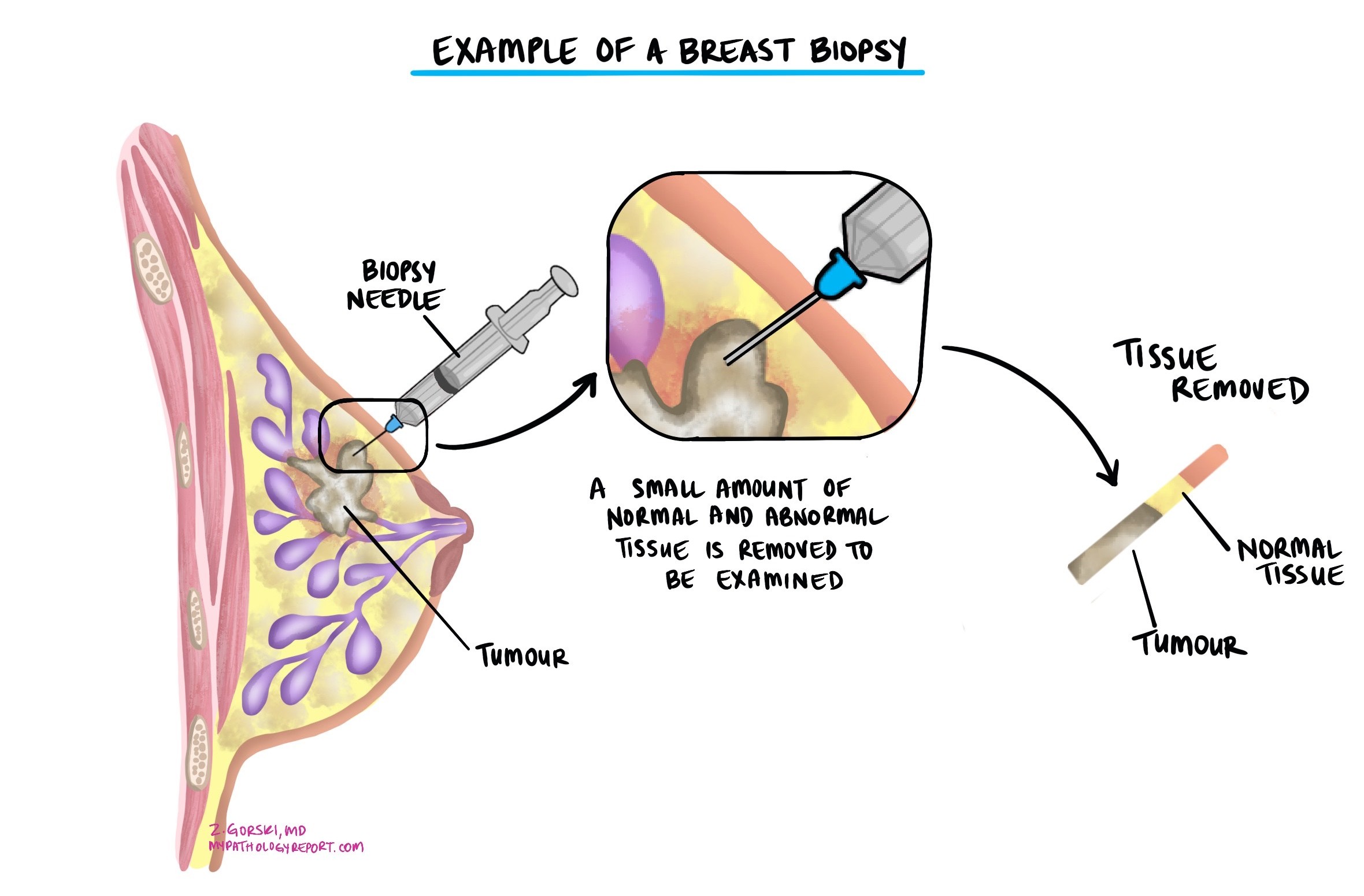

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of invasive lobular carcinoma is usually made after a small tumour sample is removed in a procedure called a biopsy. The tissue is then sent to a pathologist for examination under a microscope. You may then be offered additional surgery to remove the tumour completely.

Classic versus pleomorphic type lobular carcinoma

Pathologists categorise invasive lobular carcinoma into classic and pleomorphic types based on the appearance of the cancer cells when examined under a microscope. The tumour type is important because the pleomorphic type of invasive lobular carcinoma is more likely to metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes and other parts of the body.

- Classic type – This is the most common type of invasive lobular carcinoma. The cancer cells are small and travel through the tissue as single cells (they are not attached to other cancer cells).

- Pleomorphic type – The cancer cells in the pleomorphic type are larger and more abnormal-looking than those in the classic type. The cell’s nucleus (the part of the cell that holds most of the genetic material) is also hyperchromatic (darker) and larger than the nucleus in the classic type.

Nottingham histologic grade

The Nottingham histologic grade is a system used to assess the aggressiveness of invasive lobular carcinoma by examining the cancer cells under a microscope. The grade is determined by looking at three specific features:

- Tubule formation: This refers to the proportion of the tumor that is composed of round, gland-like structures called tubules. Tumors with more tubule formation tend to be less aggressive.

- Nuclear pleomorphism: This describes how abnormal the cancer cell’s nucleus (the part of the cell that contains the DNA) looks compared to normal cells and how much variability there is between cells. The more abnormal it appears, the higher the grade.

- Mitotic rate: This measures the number of cells in the tumor that are dividing to form new cells. A higher number of mitotic figures suggests a more aggressive tumour.

Each of these features is given a score from 1 to 3, and the scores are added together to determine the final grade:

- Grade 1 (low grade): These tumours grow more slowly and are less likely to metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes.

- Grade 2 (intermediate grade): These tumours grow moderately and are more aggressive, with a higher risk of metastasizing to lymph nodes.

- Grade 3 (high grade): These tumours tend to grow quickly and are associated with a high risk of metastatic disease.

Tumour size

The size of a breast tumour is important because it is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT) and because larger tumours are more likely to metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes and other parts of the body. The tumour size can only be determined after the entire tumour has been removed. For this reason, it will not be included in your pathology report after a biopsy.

Hormone receptors – ER and PR

ER (estrogen receptor) and PR (progesterone receptor) are proteins in some breast cancer cells. These receptors bind to the hormones estrogen and progesterone, respectively. When these hormones attach to their receptors, they can stimulate cancer cells to grow. The presence or absence of these receptors can classify invasive ductal carcinoma, which is important for determining treatment options and prognosis.

Why is the assessment of ER and PR important?

The presence of ER and PR in breast cancer cells means the cancer is hormone receptor-positive. This type of cancer is often treated with hormone (endocrine) therapy, which blocks the cancer cells’ ability to use hormones. Common hormone therapies include tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors (such as anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane), and drugs that lower hormone levels or block the receptors. Hormone receptor-positive cancers often respond well to these therapies.

Hormone receptor-positive breast cancers generally have a better prognosis than hormone receptor-negative cancers. They tend to grow more slowly and are less aggressive. Additionally, hormone receptor-positive cancers are more likely to respond to hormone therapies, which can reduce the risk of recurrence and improve long-term outcomes.

How are ER and PR assessed and reported?

ER and PR status is assessed through immunohistochemistry (IHC), performed on a tumour tissue sample obtained from a biopsy or surgery. The test measures the presence of these hormone receptors inside the cancer cells.

Here’s how the results are typically reported:

- Percentage of positive cells: Your report may include the percentage of cancer cells with ER and PR receptors. For example, a report might state that 80% of the tumour cells are ER-positive and 70% are PR-positive.

- Intensity of staining: The staining intensity (weak, moderate, or strong) reflects the number of receptors present in the nucleus of the cancer cells. This can help determine the likelihood of a response to hormone therapy.

- Allred score or H-score: Some reports may use a scoring system like the Allred score or H-score, which combines the percentage of positive cells and the intensity of staining to give an overall score. Higher scores indicate a higher likelihood that hormone therapy will be effective.

HER2

HER2, or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, is a protein that is found on the surface of some breast cancer cells. It plays a role in cell growth and division. In some breast cancers, the HER2 gene is amplified, leading to an overproduction of the HER2 protein. This condition is referred to as HER2-positive breast cancer.

Why is the assessment of HER2 important?

HER2-positive breast cancers generally have a different prognosis compared to HER2-negative ones. Before the advent of targeted therapies, HER2-positive cancers were associated with a worse prognosis. However, with effective HER2-targeted treatments, the prognosis for these patients has improved significantly. Knowing the HER2 status also helps in planning the overall management of the disease. For instance, in addition to targeted therapy, HER2-positive patients might receive a combination of chemotherapy and other treatments tailored to their specific cancer profile.

How is HER2 assessed in invasive lobular carcinoma?

HER2 status is assessed through tests performed on a tumour tissue sample, which may be obtained through a biopsy or during surgery. The two main tests used are:

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): This test measures the amount of HER2 protein on the surface of cancer cells. The results are reported as a score from 0 to 3+. A score of 0 or 1+ is considered HER2-negative, 2+ is borderline, and 3+ is HER2-positive.

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH): This test looks for the number of copies of the HER2 gene within the cancer cells. It is often used to confirm borderline IHC results. If the FISH test shows more copies of the HER2 gene than normal, the cancer is considered HER2-positive.

Tumour extension

Invasive lobular carcinoma starts inside the breast, but the tumour may spread into the overlying skin or the muscles of the chest wall. Tumour extension is used when tumour cells are found in the skin or muscles below the breast. Tumour extension is important because it is associated with a higher risk that the tumour will grow back after treatment (local recurrence) or that cancer cells will travel to a distant body site, such as the lung. It is also used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) in the context of invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast refers to cancer cells within the lymphatic vessels or blood vessels near the tumour. This indicates that the cancer can spread beyond its original site through the body’s circulatory systems. LVI can only be identified after a pathologist examines tissue under a microscope. Pathologists look for cancer cells within the lumen of lymphatic or blood vessels, which may appear as clusters or single cells surrounded by a clear space, indicating vessel walls.

The presence of LVI is an important prognostic factor in breast cancer. It is associated with a higher risk of recurrence and metastasis, as the cancer cells can travel to distant parts of the body via the lymphatic system or bloodstream. This finding often prompts a more aggressive treatment approach, which may include additional chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or targeted therapy, depending on other factors such as the overall stage of the cancer, hormone receptor status, and HER2 status.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of a tissue cut when removing a tumour from the body. The margins described in a pathology report are very important because they tell you if the entire tumour was removed or if some of the tumour was left behind. The margin status will determine what (if any) additional treatment you may require.

Most pathology reports only describe margins after a surgical procedure called an excision or resection has been performed to remove the entire tumour. For this reason, margins are not usually described after a biopsy is performed to remove only part of the tumour. The number of margins described in a pathology report depends on the types of tissues removed and the tumour’s location. The size of the margin (the amount of normal tissue between the tumour and the cut edge) depends on the type of tumour being removed and the location of the tumour.

Pathologists carefully examine the margins to look for tumour cells at the cut edge of the tissue. If tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, the margin will be described as positive. If no tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, a margin will be described as negative. Even if all of the margins are negative, some pathology reports will also measure the closest tumour cells to the cut edge of the tissue.

A positive (or very close) margin is important because it means that tumour cells may have been left behind in your body when the tumour was surgically removed. For this reason, patients with a positive margin may be offered another surgery to remove the rest of the tumour or radiation therapy to the area of the body with the positive margin.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped structures that are part of the immune system. They act as filters, trapping bacteria, viruses, and cancer cells. Lymph nodes contain immune cells that can attack and destroy harmful substances carried in the lymph fluid, which circulates throughout the body.

Why is the examination of lymph nodes important?

Examining lymph nodes is important for understanding the spread of invasive lobular carcinoma. When breast cancer spreads, it often moves first to the nearby lymph nodes before reaching other parts of the body. By examining these lymph nodes, your pathologist can determine whether the cancer has spread beyond the breast. This information is used for cancer staging, planning treatment, and assessing prognosis. If cancer is found in the lymph nodes, it may indicate a higher risk of recurrence and the need for more aggressive treatment.

What lymph nodes are typically examined for patients with invasive lobular carcinoma?

For patients with invasive lobular carcinoma, the lymph nodes that are typically examined include:

- Axillary lymph nodes: These are located under the arm and are the most common lymph nodes examined in breast cancer. They are divided into levels based on their position relative to the pectoral muscles.

- Sentinel lymph nodes: These are the first few lymph nodes to which cancer cells are likely to spread from the primary tumour. A sentinel lymph node biopsy is a procedure in which one or a few nodes are removed and tested for cancer cells.

- Internal mammary lymph nodes: These are located near the breastbone and are sometimes examined, especially if cancer is found in the sentinel lymph nodes or if imaging tests suggest their involvement.

How will the results of the lymph node examination be reported?

The results of the lymph node examination will be detailed in your pathology report.

The report will include information on:

- Number of lymph nodes examined: The total number of lymph nodes removed and examined.

- Number of positive lymph nodes: The number of lymph nodes that contain cancer cells.

- Size of the deposit: Your report will typically include the size of the largest tumour deposit found in a lymph node.

- Other features: Sometimes, additional features, such as extranodal extension (cancer spreading outside the lymph node), will be noted.

What are isolated tumour cells (ITCs)?

Pathologists use the term ‘isolated tumour cells’ to describe a group of tumour cells measuring 0.2 mm or less and found in a lymph node. Lymph nodes with only isolated tumour cells (ITCs) are not counted as being ‘positive’ for the pathologic nodal stage (pN).

What is a micrometastasis?

A ‘micrometastasis’ is a group of tumour cells measuring 0.2 mm to 2 mm in a lymph node. If only micrometastases are found in all the lymph nodes examined, the pathologic nodal stage is pN1mi.

What is a macrometastasis?

A ‘macrometastasis’ is a group of tumour cells measuring more than 2 mm and found in a lymph node. Macrometastases are associated with a worse prognosis and may require additional treatment.

Lobular carcinoma in situ

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) is a non-invasive tumour that arises before the development of invasive lobular carcinoma. Because LCIS leads to invasive lobular carcinoma, it is common for pathologists to find LCIS and invasive lobular carcinoma in the same tissue.

Treatment effect

If you received treatment (either chemotherapy or radiation therapy) before the tumour was removed, your pathologist will examine all of the tissue submitted to see how much of the tumour is still alive (viable). Lymph nodes with cancer cells will also be examined for treatment effects. A greater treatment effect (no or very few remaining viable tumour cells) is associated with better disease-free and overall survival.

Pathologic stage for invasive lobular carcinoma

The pathologic staging system for invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast helps doctors understand how far the cancer has spread and plan the best treatment. The system mainly uses the TNM staging, which stands for Tumor, Nodes, and Metastasis. Early-stage cancers (like T1 or N0) might only require surgery and possibly radiation, while more advanced stages (like T3 or N3) may need a combination of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies. Proper staging ensures that patients receive the most effective treatments based on the extent of their disease, which can improve survival rates and quality of life.

Tumour stage (pT)

This feature examines the size and extent of the breast tumour. The tumour is measured in centimetres, and its growth beyond the breast tissue is assessed.

T0: No evidence of primary tumour. This means no tumour can be found in the breast.

T1: The tumour is 2 centimetres or smaller in greatest dimension. This stage is further subdivided into:

- T1mi: Tumour is 1 millimetre or smaller.

- T1a: Tumor is larger than 1 millimetre but not larger than 5 millimetres.

- T1b: Tumour is larger than 5 millimetres but not larger than 10 millimetres.

- T1c: Tumor is larger than 10 millimetres but not over 20 millimetres.

T2: The tumour is larger than 2 centimetres but not larger than 5 centimetres.

T3: The tumour is larger than 5 centimetres.

T4: The tumour has spread to the chest wall or skin, regardless of its size. This stage is further subdivided into:

- T4a: Tumour has invaded the chest wall.

- T4b: Tumour has spread to the skin, causing ulcers or swelling.

- T4c: Both T4a and T4b are present.

- T4d: Inflammatory breast cancer, characterized by redness and swelling of the breast skin.

Nodal stage (pN)

This feature examines if the cancer has spread to the nearby lymph nodes, which are small, bean-shaped structures found throughout the body.

N0: No cancer is found in the nearby lymph nodes.

N1: Cancer has spread to 1 to 3 axillary lymph nodes (under the arm).

N2: Cancer has spread to:

- N2a: 4 to 9 axillary lymph nodes.

- N2b: Internal mammary lymph nodes without involvement of axillary lymph nodes.

N3: Cancer has spread to:

- N3a: 10 or more axillary lymph nodes or two infraclavicular lymph nodes (below the collarbone).

- N3b: Internal mammary lymph nodes and axillary lymph nodes.

- N3c: Supraclavicular lymph nodes (above the collarbone).

What is the prognosis for a person diagnosed with invasive lobular carcinoma?

The prognosis for invasive lobular carcinoma depends on various factors, including the tumour size, stage, and grade. In general, most invasive lobular carcinomas are low grade, express estrogen receptors, and grow slowly. These features are associated with a favourable outcome. However, some studies suggest that the long-term prognosis for invasive lobular carcinoma may be less favourable compared to other types of breast cancer, with a higher risk of distant metastases or recurrence many years after the initial diagnosis.

Invasive lobular carcinoma has a distinct pattern of metastasis, often spreading to the bone, gastrointestinal tract, or ovaries rather than the lungs, which are a common site of metastasis for other breast cancers. This unique pattern may require additional monitoring and tailored treatment strategies.

Some histological subtypes of invasive lobular carcinoma, such as the pleomorphic and solid types, are associated with a worse prognosis. By contrast, the classic type is often low grade and has a better outcome.

About this article

Doctors wrote this article to help you read and understand your pathology report. Contact us with any questions about this article or your pathology report. Read this article for a more general introduction to the parts of a typical pathology report.