by Emily Goebel, MD FRCPC

October 9, 2025

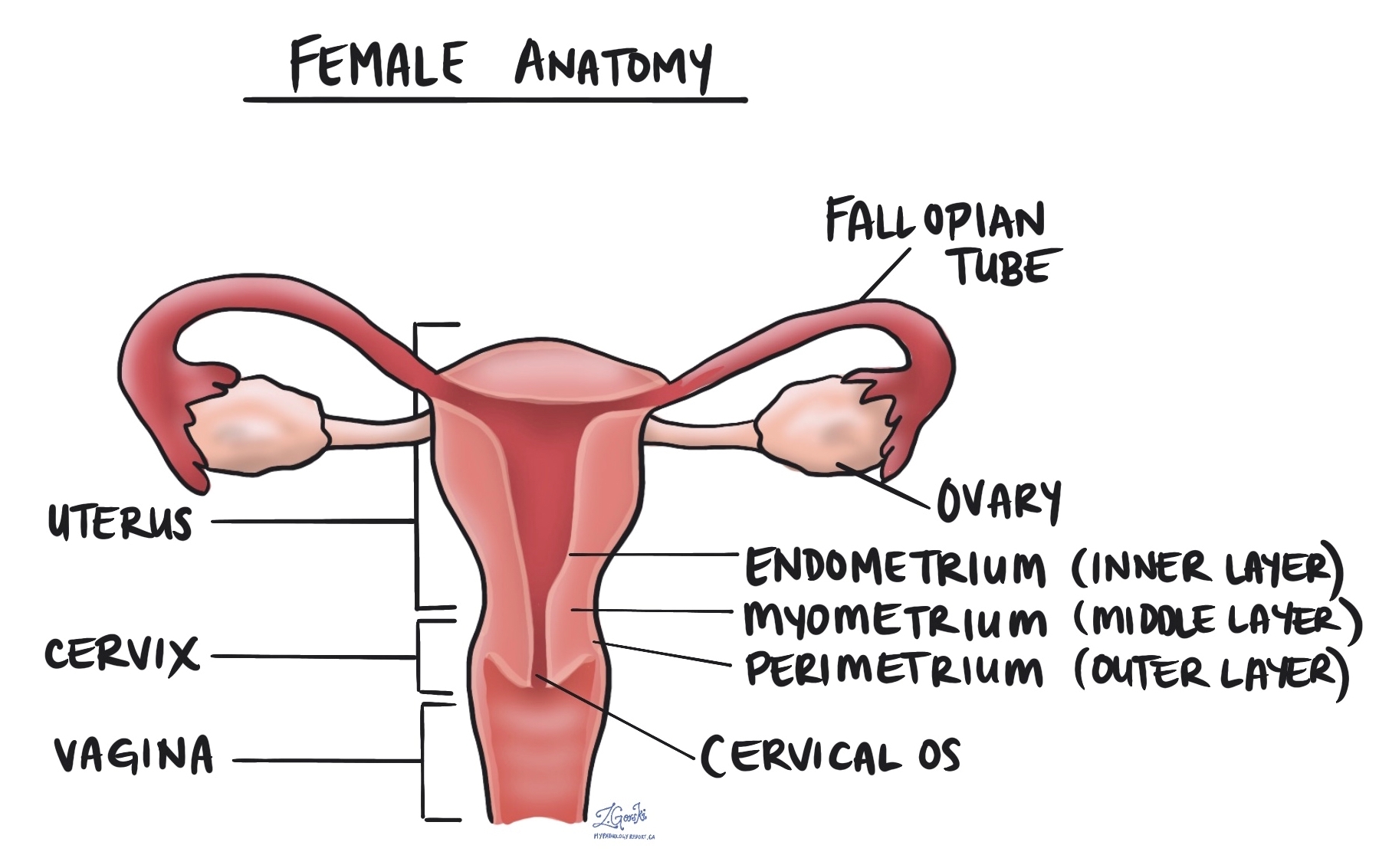

Endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) is a precancerous condition that affects the lining of the uterus, called the endometrium. In this condition, the glands that make up the endometrium become abnormal in both number and appearance, causing the tissue to become thicker than normal.

It is called a precancerous condition because over time, EIN can develop into a type of uterine cancer known as endometrioid carcinoma, the most common form of endometrial (uterine) cancer.

Another name for endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia is atypical endometrial hyperplasia, a term used in older reports.

Is endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia cancer?

No. EIN is not cancer, but it is closely related to cancer. It is called a precancerous condition because if left untreated, it can develop into endometrioid carcinoma over time. Detecting and treating EIN early significantly reduces the risk of cancer developing later.

What are the symptoms of endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia?

The most common symptom of EIN is abnormal uterine bleeding, which may include:

-

Heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding.

-

Bleeding between menstrual periods.

-

Bleeding after menopause.

Some people may also notice irregular cycles or spotting. A doctor should always evaluate any bleeding after menopause.

Who gets endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia?

Endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) most often affects people between 50 and 55 years old, particularly those who are perimenopausal or postmenopausal.

It is more common in individuals who have long-term exposure to estrogen without enough progesterone to balance it.

Risk factors for developing EIN include:

-

Irregular or absent ovulation (as in polycystic ovary syndrome).

-

Obesity.

-

Estrogen-only hormone therapy.

-

Diabetes or high blood pressure.

EIN can also develop in people with hereditary cancer syndromes, such as Lynch syndrome and Cowden syndrome, which increase the risk of developing endometrial and other types of cancer. If your doctor suspects one of these conditions, they may recommend genetic counseling or genetic testing.

How does endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia develop?

EIN develops when the endometrium grows for too long under the influence of estrogen without enough progesterone to balance it.

During a normal menstrual cycle, the endometrium grows and changes in response to these hormones:

-

In the proliferative phase, estrogen causes the endometrium to grow and thicken.

-

After ovulation, progesterone helps the lining mature and prepare for a possible pregnancy (the secretory phase).

-

If pregnancy does not occur, both hormones drop, and the lining is shed during menstruation.

When ovulation does not occur regularly or progesterone levels are too low, the endometrium remains under the influence of estrogen for too long. This prolonged exposure causes the glands to grow excessively and develop abnormal cellular changes. Over time, these changes can become endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia.

What causes increased estrogen levels?

Several conditions and medications can lead to higher or prolonged levels of estrogen, including:

-

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A hormonal condition that prevents regular ovulation.

-

Obesity: Fat tissue converts other hormones into estrogen, raising overall estrogen levels.

-

Estrogen-only hormone therapy: Taking estrogen without progesterone, often after menopause.

-

Tamoxifen: A medication used for breast cancer that can act like estrogen in the uterus.

-

Perimenopause: The years before menopause, when ovulation becomes irregular and progesterone levels drop.

How is the diagnosis of endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia made?

A pathologist makes the diagnosis of EIN after examining a small sample of the uterine lining under the microscope. This sample is usually taken by an endometrial biopsy or a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure, which removes a small amount of endometrial tissue for testing.

What does endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, the endometrium in EIN shows:

-

Crowded glands that are close together and irregular in shape.

-

Atypical glandular cells, which have larger, darker, or more irregular nuclei than normal.

-

Less supporting stroma, the tissue that normally separates the glands.

Pathologists use the word atypia to describe cells that look abnormal compared to normal endometrial gland cells. This atypia distinguishes endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia from endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, which features crowded glands but normal-looking cells.

Pathologists may also perform immunohistochemistry, a special laboratory test, to check for loss of specific proteins such as PTEN, PAX2, or mismatch repair proteins. These findings support the diagnosis and can sometimes suggest an inherited condition like Lynch syndrome.

What does endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia look like on imaging or during surgery?

EIN may not form a visible mass, but sometimes the endometrium appears thicker than normal on ultrasound or hysteroscopy. Occasionally, a small polyp-like area can be seen or removed for biopsy. These areas are usually localized rather than widespread.

What is the relationship between EIN and endometrial cancer?

Endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia is closely related to endometrioid carcinoma, the most common type of endometrial cancer. In fact, about one in three women diagnosed with EIN on biopsy already have small areas of cancer in the uterus that were not detected in the initial sample.

For this reason, doctors often recommend surgical removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) to make sure there is no hidden cancer and to prevent new cancer from developing.

Can endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia turn into cancer?

Yes. EIN is a precancerous condition, and without treatment, it can develop into endometrioid carcinoma. The estimated risk of progression to cancer is about 25% to 40% over several years.

Treatment significantly reduces this risk, and most people diagnosed with EIN do not develop cancer after appropriate management.

What are the treatment options for endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia?

Treatment depends on several factors, including your age, whether you are premenopausal or postmenopausal, and whether you wish to have children in the future.

Common treatment options include:

-

Hysterectomy: Surgical removal of the uterus is the most effective treatment, especially for people who have completed childbearing or are postmenopausal. The fallopian tubes and ovaries are often removed at the same time.

-

Progestin therapy: For those who wish to preserve fertility or avoid surgery, progestin (a synthetic form of progesterone) can be given orally, by injection, or through a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (IUD). Progestin helps counteract the effects of estrogen and can cause the abnormal cells to return to normal.

-

Follow-up biopsy: Regular biopsies or ultrasounds are used to confirm that the abnormal cells have resolved and to monitor for recurrence.

Treatment is usually very effective, especially when started early.

What is the prognosis for endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia?

The prognosis for EIN is excellent when treated appropriately. Most patients are cured after a hysterectomy or successful hormonal therapy. Regular follow-up is essential, especially for those treated without surgery, to ensure that the abnormal tissue does not return or progress to cancer.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What features were seen in my biopsy that confirm EIN?

-

What are my treatment options?

-

Do I need a hysterectomy, or can I try hormone therapy first?

-

How often will I need follow-up biopsies or imaging?

-

What is my risk of developing endometrial cancer in the future?

-

Are there steps I can take to lower my estrogen levels or prevent recurrence?

-

Should I consider genetic testing for conditions like Lynch syndrome?