by Catherine Forse MD FRCPC and Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

April 17, 2025

Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is a type of cancer that develops from glandular cells within the esophagus, the tube that carries food from your mouth to your stomach. This type of cancer typically develops in the lower part of the esophagus, near the stomach, in an area known as the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is often associated with Barrett’s esophagus, a condition caused by prolonged acid reflux, also known as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Understanding the esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular tube connecting your throat (pharynx) to your stomach. Its main job is to move food and liquids from your mouth to your stomach, where digestion begins. When you swallow, muscles in your esophagus contract in coordinated waves (peristalsis), pushing food downward. The esophagus has muscular valves called sphincters at each end. These sphincters open to allow food to pass and close to prevent stomach contents from moving back up into the throat.

What are the symptoms of adenocarcinoma in the esophagus?

Common symptoms of adenocarcinoma in the esophagus include:

-

Difficulty swallowing, especially solid foods.

-

Chest pain or discomfort.

-

Worsening acid reflux symptoms.

-

Unexplained weight loss.

What causes adenocarcinoma of the esophagus?

Adenocarcinoma typically develops from Barrett’s esophagus, a condition caused by long-term exposure of the esophagus to stomach acid (acid reflux or GERD). Repeated acid exposure alters the normal cells lining the esophagus, known as squamous cells, into glandular cells resembling those found in the small intestine. This process is known as intestinal metaplasia. Over time, Barrett’s esophagus may develop into dysplasia, a precancerous condition. Dysplasia involves abnormal cells that can eventually develop into adenocarcinoma.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of adenocarcinoma is usually made after an upper endoscopy, during which a doctor performs a biopsy to remove a small tissue sample from a suspicious area in the esophagus. A pathologist examines the biopsy under a microscope to confirm the presence of cancer. If cancer is found, additional tests such as imaging scans or blood tests may be performed to determine the extent of the disease.

Your pathology report for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus

A pathology report is a medical document prepared by a pathologist, a doctor who specializes in examining tissues under the microscope. This report provides essential details about your diagnosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma. The type of information included in your pathology report depends on the procedure performed—whether you had a biopsy (a small tissue sample), an endoscopic resection, or surgery to remove the entire tumor. The sections below explain key terms and features commonly found in pathology reports for esophageal adenocarcinoma, helping you understand your results and their significance for your treatment and prognosis.

Histologic grade

Pathologists assign a histologic grade to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus based on how closely the cancer cells resemble normal glandular cells when viewed under the microscope. The grade provides important information about how quickly the tumor is likely to grow and spread.

Grade 1 – Well differentiated adenocarcinoma

In this grade, more than 95% of the tumor cells form well-organized glands, closely resembling normal esophageal glandular tissue. Well differentiated tumors typically grow slowly and are less likely to spread to other parts of the body, which usually means a better prognosis.

Grade 2 – Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma

In moderately differentiated tumors, between 50% and 95% of tumor cells form glands. These tumors exhibit greater variability in the appearance of the cancer cells compared to grade 1 tumors. Moderately differentiated tumors tend to behave more aggressively than well differentiated tumors and have a somewhat higher likelihood of metastasizing.

Grade 3 – Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated adenocarcinoma

Grade 3 tumors form glands in less than 50% of the tumor, or sometimes not at all. Poorly differentiated tumors look very abnormal under the microscope and differ significantly from normal cells. Tumors described as undifferentiated show no gland formation and represent the most aggressive end of this grade. Poorly differentiated and undifferentiated tumors grow rapidly, are more aggressive, and have a higher likelihood of spreading to lymph nodes or distant organs.

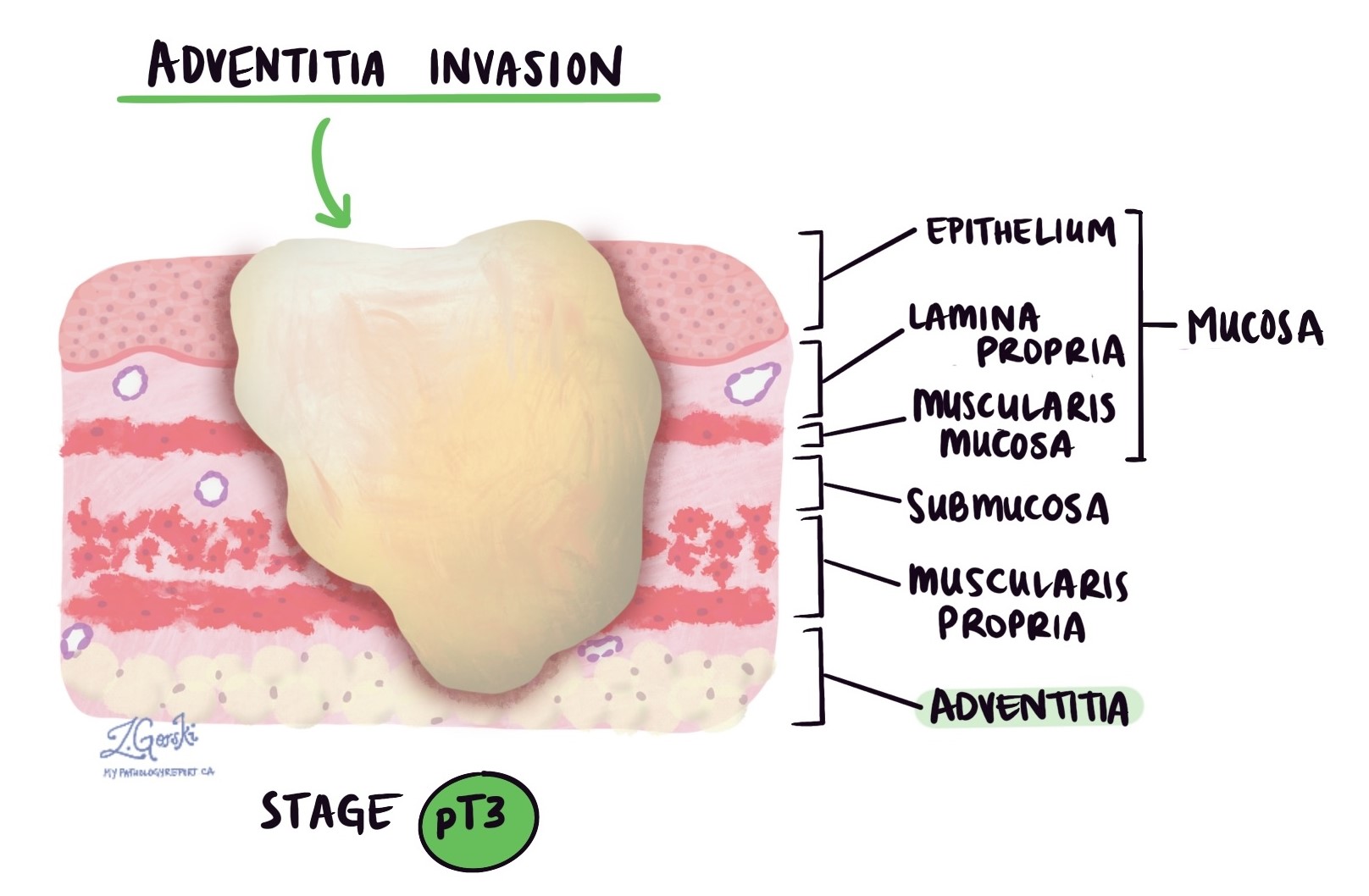

Depth of invasion and pathologic tumor stage (pT)

Adenocarcinoma originates in a thin layer of tissue within the esophagus, known as the mucosa. When the tumor is located entirely within the mucosa, it is referred to as intramucosal adenocarcinoma. Patients with intramucosal adenocarcinoma typically have a better overall prognosis because the cancer cells are less likely to spread to other parts of the body, such as lymph nodes.

In pathology, the term “invasion” describes the spread of cancer cells from their original site into surrounding organs or tissues. As adenocarcinoma in the esophagus grows, cancer cells can spread from the mucosa into the deeper layers of tissue beneath. Once this occurs, the disease is referred to as invasive adenocarcinoma.

When examining your tumor under the microscope, your pathologist will determine how deeply the cancer cells have spread from the mucosa into the underlying layers of tissue. This measurement is referred to as the depth or level of invasion, and it is crucial for understanding your prognosis and planning treatment. Tumors that invade deeper into the esophageal wall are more likely to spread to other parts of the body, such as lymph nodes, the liver, or the lungs. Your pathologist will use the depth of invasion to assign the pathologic tumor stage (pT), which guides your treatment options and helps predict outcomes.

The following list explains the possible pathologic tumor stages (pT):

- pT1: Tumor cells have invaded the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa (superficial layers beneath the mucosa).

- pT1a: Tumor invades only into the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae (thin layers within the mucosa).

- pT1b: Tumor invades into the submucosa (the layer of tissue just below the mucosa).

- pT2: Tumor invades into the muscularis propria (the thick muscle layer deeper in the esophageal wall).

- pT3: Tumor invades through the muscle layer into the adventitia (the outermost tissue layer covering the esophagus).

- pT4: Tumor has grown beyond the esophagus and invades nearby structures.

- pT4a: Tumor invades nearby structures such as the pleura (lung lining), pericardium (heart lining), azygos vein, diaphragm, or peritoneum (abdominal lining).

- pT4b: Tumor invades other critical adjacent structures like the aorta (major blood vessel), vertebral body (spinal bones), or airways.

HER2

HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) is a protein found on esophageal cancer cells that facilitates their growth and division. Tumours with extra HER2 proteins due to a change (amplification) in the HER2 gene are called HER2-positive.

HER2-positive cancers tend to be more aggressive and were once associated with a poorer prognosis. However, effective targeted therapies now significantly improve outcomes for patients with HER2-positive cancers. Knowing the HER2 status helps your doctors choose treatments specifically designed for your type of cancer, often including targeted drugs along with chemotherapy.

Two tests are commonly performed to measure HER2 in breast cancer cells: immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for HER2

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a test pathologists use to measure the amount of HER2 protein on the surface of the cancer cells. To perform this test, pathologists use a small tissue sample from the tumour. They apply special antibodies to the tissue, which bind to HER2 proteins if they are present. These antibodies are then made visible under a microscope by adding a colored dye. By examining the intensity (strength) and amount of colour present, the pathologist determines how much HER2 protein is on the cancer cells.

Your pathology report will describe the results of HER2 IHC testing as a score ranging from 0 to 3+:

-

0 (negative): No visible staining, meaning no significant HER2 protein is detected. This indicates a HER2-negative tumour, and targeted HER2 treatments will not typically be helpful.

-

1+ (negative): Weak and incomplete staining. These tumors are still considered HER2-negative and usually do not benefit from HER2-targeted treatments.

-

2+ (borderline or equivocal): Moderate staining, meaning the result is unclear. Additional testing, typically a FISH test, is required to determine whether the cancer is HER2-positive or HER2-negative.

-

3+ (positive): Strong and complete staining on the surface of the cancer cells. This indicates a HER2-positive cancer. HER2-positive cancers often grow more rapidly but respond very well to HER2-targeted therapies, such as trastuzumab.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for HER2

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a diagnostic test used to examine cancer cells for extra copies of specific genes, such as the HER2 gene. In esophageal cancer testing, FISH is usually performed after the initial HER2 IHC test gives unclear or borderline results.

To perform a FISH test, pathologists use a small tissue sample from the tumour. They add special fluorescent probes to the tissue, which attach specifically to the HER2 genes inside the cancer cells. Under a microscope, these probes glow brightly, enabling pathologists to count the number of copies of the HER2 gene present in each cell.

Your pathology report will typically describe the results of the FISH test as either:

-

Positive (Amplified): Cancer cells contain too many copies of the HER2 gene. This is known as HER2-positive cancer. These cancers often grow more aggressively but typically respond well to targeted HER2 treatments, such as trastuzumab (Herceptin).

-

Negative (Non-amplified): Cancer cells have a normal number of HER2 gene copies. This is referred to as HER2-negative cancer, indicating that targeted HER2 therapies are typically not effective.

Sometimes the report may describe the exact number of gene copies per cell (for example, an average HER2 copy number or a HER2-to-chromosome ratio). These detailed numbers help pathologists and oncologists accurately confirm the HER2 status, guiding the choice of the most effective treatment for your specific cancer type.

Mismatch repair (MMR) protein

Mismatch repair proteins (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, MSH6) fix mistakes in DNA. If one or more of these proteins are missing or lost, the cells accumulate genetic errors, which increases the risk of cancer and influences treatment strategies, such as immunotherapy. Pathologists perform immunohistochemistry (IHC) to assess the expression of these four proteins in the cancer cells.

MMR results are reported as:

-

Normal (intact): All proteins present (retained expression). This means your cells can repair DNA damage normally.

-

Abnormal (loss of expression): One or more proteins are missing. If MMR proteins are lost, your tumor may respond better to immunotherapy. Additionally, it could indicate Lynch syndrome, a genetic condition increasing the risk of multiple cancers.

PD-L1 testing

PD-L1 is a protein some cancer cells produce to avoid being detected and attacked by your immune system. Testing for PD-L1 helps doctors decide if treatments using immune checkpoint inhibitors (a type of immunotherapy) may be beneficial.

Results of PD-L1 testing in the esophagus are reported as a combined positive score (CPS):

-

Positive (CPS ≥ 1): Immunotherapy may be an effective treatment option.

-

Negative (CPS <1): Immunotherapy is less likely to be effective.

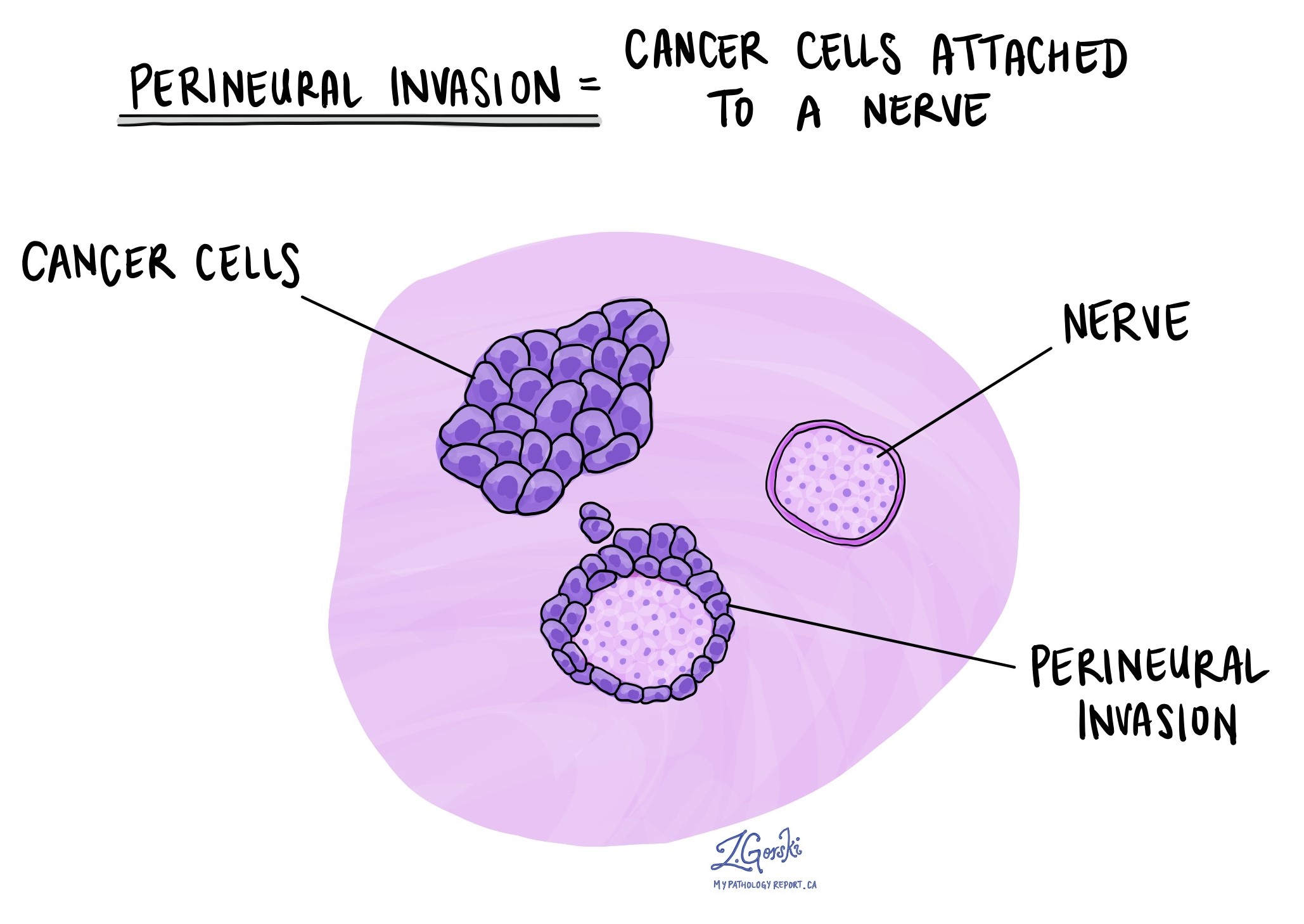

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion (PNI) indicates that cancer cells have infiltrated or attached to nerves, suggesting a higher likelihood of cancer recurrence or metastasis.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means that cancer cells have entered small blood vessels or lymphatic channels located near the tumour in the esophagus. Blood vessels are small tubes that carry blood to and from tissues, delivering oxygen and nutrients. Lymphatic vessels are similar but carry lymph fluid, which contains immune cells and helps remove waste from tissues. Both types of vessels can provide pathways for cancer cells to spread beyond the original tumour site.

Pathologists carefully examine tissue samples under the microscope to look for LVI. Cancer cells may appear as single cells or clusters inside these vessels, often surrounded by a clear space that marks the vessel wall. Your pathology report will typically describe LVI as “positive” (or “present”) if cancer cells are found inside these vessels, or “negative” (or “absent”) if no cancer cells are seen.

The presence of LVI is important because it suggests a higher chance that cancer will spread to nearby lymph nodes or may spread to distant parts of the body. Because of this, your medical team may recommend more aggressive treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or targeted therapy, to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence and spread.

Margins

In pathology, a margin refers to the edge or border of tissue removed along with a tumor during surgery. Margins are closely examined under a microscope by a pathologist to see if any cancer cells are present at the cut edge. The status of these margins is important because it helps determine if the entire tumour was removed or if cancer cells may have been left behind in the body.

Margins are typically assessed only after a surgical procedure, such as a resection or excision, which removes the entire tumour. They are usually not described following a biopsy, as biopsies remove only a small sample of tissue, not the whole tumour. The number and type of margins described in your pathology report depend on the size and location of the tumour, as well as the type of tissue removed.

Margin status is reported as:

-

Negative margin: No cancer cells found at the tissue edges; tumor completely removed.

-

Positive margin: Cancer cells present at the tissue edges, indicating the tumor may remain.

Types of margins evaluated:

-

Mucosal (lateral) margin: The edge of tissue lining the inside surface of the esophagus surrounding the tumor.

-

Deep margin: The tissue beneath the tumor inside the esophageal wall.

-

Proximal margin: The upper tissue edge of the esophagus closer to the mouth. Checked especially during the removal of a segment or the entire esophagus.

-

Distal margin: The lower tissue edge closest to the stomach. This margin may include esophageal or stomach tissue, depending on the location of the tumor.

-

Radial margin: The tissue surrounding the outer surface of the esophagus, important when assessing whether the tumor has spread through the esophageal wall into nearby structures.

Lymph nodes and pathologic nodal stage (pN)

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. They act as filters, trapping abnormal cells such as bacteria, viruses, and cancer cells. Cancer cells from a tumor can travel to lymph nodes through tiny channels called lymphatic vessels. When cancer cells spread from the original tumor site to lymph nodes, the process is called metastasis.

Cancer cells usually migrate first to lymph nodes closest to the original tumor, although sometimes distant lymph nodes may also be involved. During surgery for esophageal adenocarcinoma, surgeons typically remove lymph nodes near the tumor to see if they contain cancer cells. They may also remove lymph nodes farther from the tumor if these nodes look enlarged or if there is suspicion of cancer spread.

After removal, the lymph nodes are carefully examined under a microscope by a pathologist. Your pathology report will describe the lymph nodes as either:

-

Positive: Cancer cells are present in the lymph node.

-

Negative: No cancer cells are found in the lymph node.

Evaluating lymph nodes is very important for two main reasons:

-

Determining the nodal stage (pN): The presence and number of lymph nodes involved with cancer determine your pathologic nodal stage, which helps doctors understand how far the cancer has spread.

-

Planning additional treatment: Finding cancer cells in lymph nodes indicates a higher likelihood that cancer cells may be present in other parts of the body, either now or in the future. This helps your doctor decide if you need additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy, to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence or spread.

Pathologic nodal staging for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is reported as follows:

-

pN0: No cancer cells found in any lymph nodes examined.

-

pN1: Cancer cells found in 1 or 2 lymph nodes.

-

pN2: Cancer cells found in 3 to 6 lymph nodes.

-

pN3: Cancer cells found in more than 6 lymph nodes.

-

pNX: No lymph nodes were available or examined by the pathologist.

Your pathology report should clearly state your nodal stage, which will help guide your doctor’s recommendations for treatment and follow-up.

Treatment effect after chemotherapy or radiation therapy

If you received chemotherapy or radiation therapy before surgery, your pathologist examines how many cancer cells remain alive after treatment. The treatment effect is scored as:

-

0: Complete response. No viable cancer cells remain.

-

1: Near-complete response. Only a few isolated cancer cells or small clusters remain.

-

2: Partial response. Some cancer cells remain, but there has been significant destruction.

-

3: Minimal or no response. Most or all cancer cells remain alive.

A lower score (0-1) generally predicts a better prognosis compared to higher scores (2-3).

Prognosis

For patients diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, prognosis depends on multiple factors described in the pathology report.

Good prognosis factors include:

-

Lower tumor grade (well differentiated).

-

Superficial tumor invasion (limited to mucosa).

-

No lymph node involvement.

-

Negative surgical margins.

-

Absence of lymphovascular or perineural invasion.

-

Absence of aggressive genetic features (HER2-negative, intact mismatch repair).

Poor prognosis factors include:

-

Higher tumor grade (poorly differentiated).

-

Deep tumor invasion (beyond mucosa).

-

Positive lymph nodes (pathologic nodal stages N1–N3).

-

Positive surgical margins.

-

Presence of lymphovascular or perineural invasion.

-

Aggressive genetic features (HER2-positive, loss of mismatch repair proteins).