by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD

November 10, 2025

Keratinizing squamous dysplasia of the larynx is a precancerous condition affecting the tissue on the inner surface of the larynx. This condition is considered a precancerous disease because it can, over time, turn into a type of laryngeal cancer called squamous cell carcinoma. Pathologists divide keratinizing squamous dysplasia into three grades – mild, moderate, and severe – and the risk of developing cancer is highest with severe squamous dysplasia.

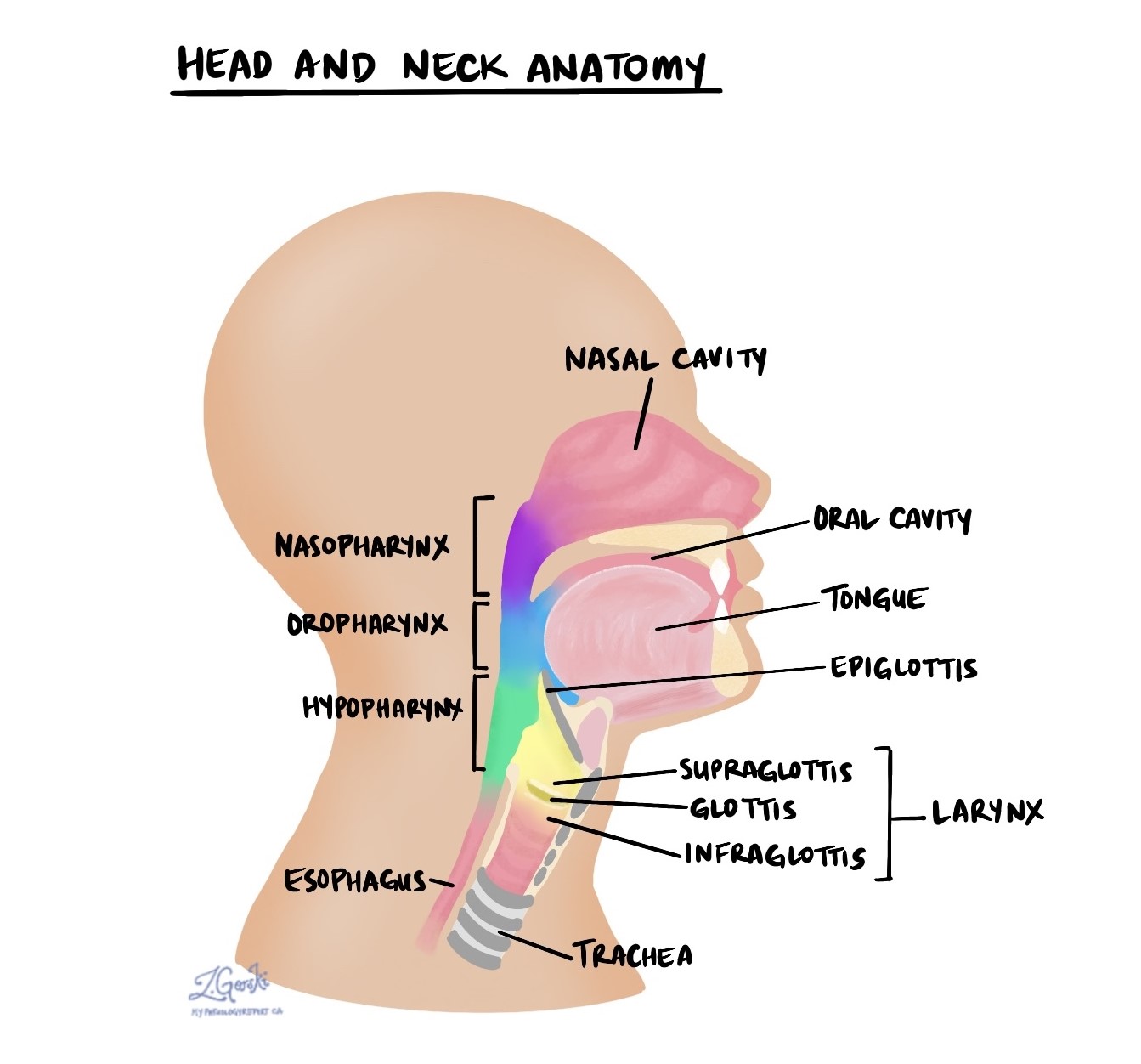

The larynx is a structure located in the upper neck just above the trachea. Its functions include protecting the airway and sound production. It is divided into three parts: the supraglottis, glottis, and subglottis. The glottis, which consists of the vocal cords, is the most common location for keratinizing squamous dysplasia. However, as the tumour grows, it can spread to other parts of the larynx. This is called transglottic extension.

What causes keratinizing squamous dysplasia in the larynx?

The most common cause of keratinizing squamous dysplasia in the larynx is smoking. Other causes include excessive alcohol consumption, immune suppression, and prior radiation to the neck.

What are the symptoms of keratinizing squamous dysplasia?

Symptoms of keratinizing squamous dysplasia of the larynx include breathing difficulties, hoarseness or voice changes, and difficulty swallowing.

Keratinizing squamous dysplasia of the larynx

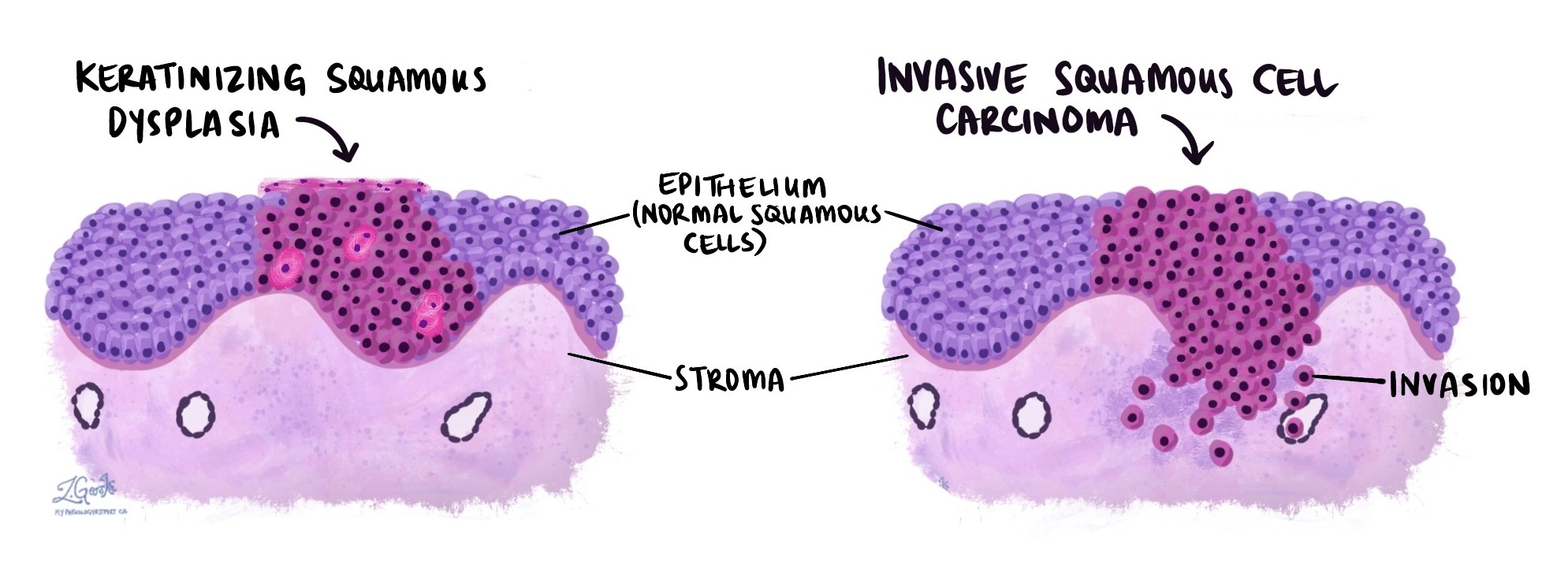

In keratinizing squamous dysplasia, abnormal squamous cells start to replace the normal, healthy squamous cells in the epithelium, a thin layer of tissue that covers the inside surface of the larynx. When examined under the microscope, the abnormal squamous cells are typically larger and hyperchromatic (darker) than the normal healthy squamous cells. Instead of showing an orderly pattern of growth and maturation, the involved epithelium tends to appear disorganized, and the abnormal squamous cells undergo a process called keratinization, which causes them to appear bright pink. Keratinization is a normal process in the skin, but it is abnormal in the larynx.

Keratinizing squamous dysplasia in the larynx is considered a precancerous and non-invasive disease because the abnormal cells are confined to the epithelium. In contrast, squamous cell carcinoma is regarded as an invasive disease and a type of cancer because the abnormal squamous cells have spread into the underlying stroma.

Grade

Keratinizing squamous dysplasia in the larynx is divided into three grades: mild, moderate, and severe. The grade is very important because it is related to the risk of developing invasive squamous cell carcinoma in the future. Mild keratinizing squamous dysplasia has a low risk of turning into cancer and is often left untreated. Moderate and severe keratinizing squamous dysplasia are associated with a much higher risk of progressing to cancer, and patients with this condition are usually offered treatment to remove the diseased tissue.

Pathologists determine the grade by comparing the abnormal squamous cells to normal, healthy squamous cells in the larynx. The grade can only be determined after the tissue is examined under the microscope by a pathologist.

Mild keratinizing squamous dysplasia of the larynx

In mild keratinizing squamous dysplasia, the abnormal squamous cells are similar in shape and colour to the normal, healthy squamous cells in the uninvolved epithelium. Mitotic figures (dividing cells) are typically still only visible at the bottom of the epithelium, and the overall maturation of the epithelium is preserved.

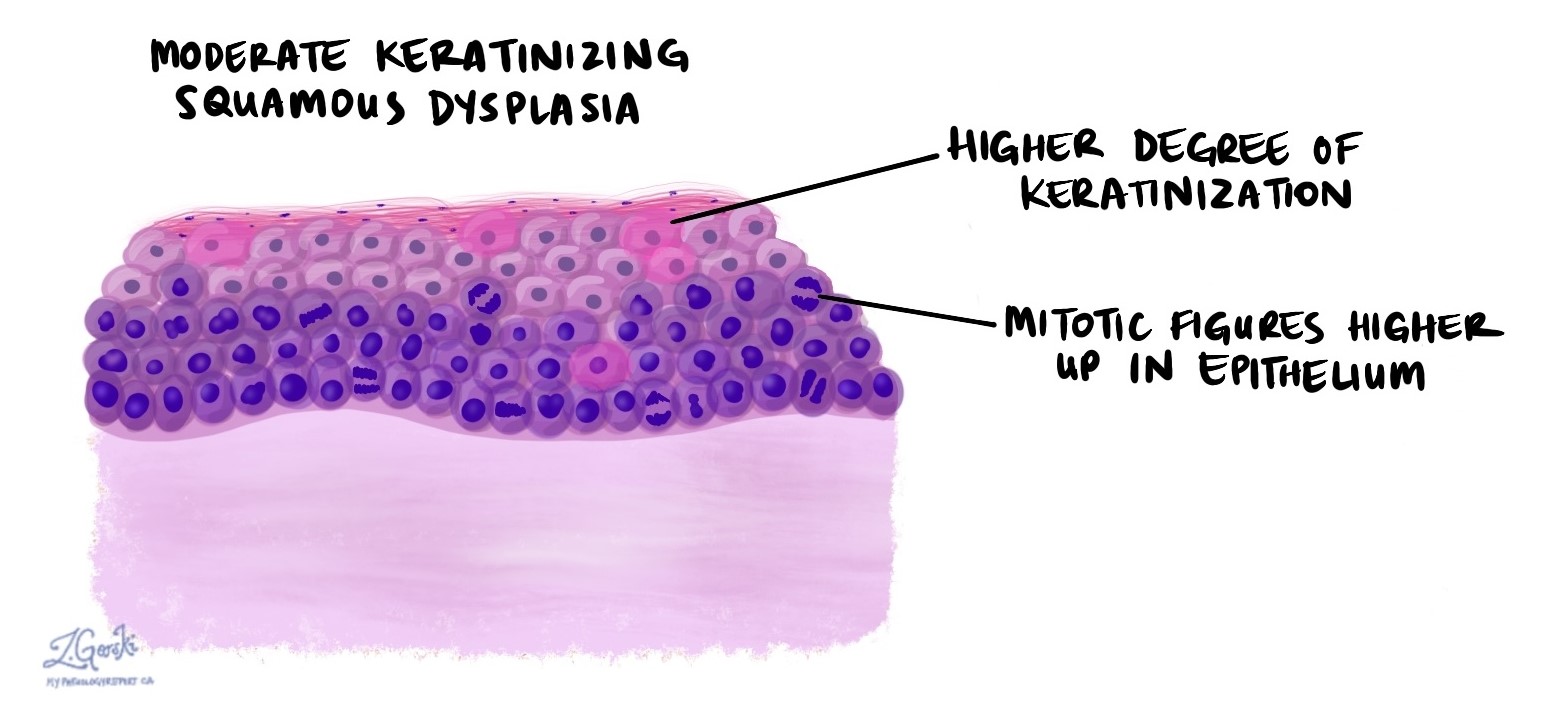

Moderate keratinizing squamous dysplasia of the larynx

In moderate keratinizing squamous dysplasia, the abnormal squamous cells are larger and hyperchromatic (darker) than the normal, healthy squamous cells. Maturation of the epithelium is disordered, and there is a greater degree of keratinization. Mitotic figures (dividing cells) may be seen higher up in the epithelium.

Severe keratinizing squamous dysplasia of the larynx

In severe keratinizing squamous dysplasia, the abnormal squamous cells are larger and hyperchromatic (darker) than the normal, healthy squamous cells. The epithelium exhibits minimal maturation, and the cells appear highly disorganized. The abnormal squamous cells often appear bright pink due to keratinization, and a thick layer of keratin may be visible on the tissue surface. Mitotic figures (cells in the process of division) are often observed at all levels of the epithelium.

Margins

In pathology, a margin refers to the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure, such as an excision or resection, aimed at removing the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are present at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was entirely removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.