by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

December 14, 2023

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a type of non-small cell lung cancer. The tumour starts from specialized squamous cells that are normally found on the inside of the airways of the lungs. These cells form a barrier called the epithelium which helps protect the airways from damage.

SCC of the lungs can be keratinizing (KSCC), non-keratinizing (NKSCC), or basaloid. Keratinizing means that the tumour cells are making a protein called keratin. Non-keratinizing means the tumour cells are not making keratin. Basaloid means that the tumour cells resemble the basal cells normally found at the base of the epithelium. Despite these differences, all three subtypes show similar behaviour and prognosis.

What causes squamous cell carcinoma of the lung?

The most common cause of SCC in the lungs is long-term exposure to cigarette smoke.

What are the symptoms of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung?

Symptoms of SCC of the lung include persistent or worsening cough, coughing up blood, chest pain, and shortness of breath. Tumours that have spread to other parts of the body may cause additional symptoms depending on the location in the body. For example, tumours that spread to bones may cause bone pain and can cause the bone to break. Doctors describe this as a pathologic fracture.

How is the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma made?

SCC of the lung is usually diagnosed after a small sample of tissue is removed in a procedure called a biopsy or a fine needle aspiration (FNA). In some situations, the diagnosis is only made after the entire tumour has been removed.

What does squamous cell carcinoma of the lung look like under the microscope?

When examined under the microscope, SCC is usually made up of large pink cells that grow in groups called sheets or nests. However, the tumour cells in squamous cell carcinoma look different from the healthy squamous cells that normally line the inside of the airways. The tumour cells are usually larger than normal squamous cells and the nucleus of the cell which holds the genetic material is darker. Pathologists describe these cells as hyperchromatic. Tumour cells also tend to show a range of shapes and sizes which pathologists describe as pleomorphic. Numerous mitotic figures (tumour cells dividing to create new tumour cells) are also usually seen.

What other tests may be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

Your pathologist may perform a test called immunohistochemistry to confirm the diagnosis. This test helps differentiate SCC from other types of lung tumours such as adenocarcinoma that can look similar under the microscope. The results will be described as positive (reactive) or negative (non-reactive).

Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung usually shows the following results:

- p40 – Positive.

- CK5 – Positive.

- TTF-1 – Negative.

- Chromogranin – Negative.

- Synaptophysin – Negative.

What happens if more than one tumour is found?

In some situations, more than one tumour is found when the lung tissue is examined under the microscope. When this happens, each tumour will be described separately in your report.

There are two possible explanations for finding more than one tumour:

- The tumour cells from one tumour have spread to another part of the lung. This explanation is more likely when all of the tumours are of the same type. For example, all of the tumours are SCC. If the tumours are on the same side as the body, the smaller tumours are called nodules. If the tumours are on different sides of the body (right and left lung), the smaller tumour is called metastasis. Tumour nodules increase the tumour stage while metastatic disease increases the metastatic stage (see Pathologic stage below). Both are associated with a worse prognosis.

- The tumours have developed separately. This is the more likely explanation when the tumours are of different types. For example, one tumour is a SCC and the other is an adenocarcinoma. In this situation, the tumours are considered separate primaries and not metastatic disease.

What does pleural invasion mean and why is it important?

The lungs are surrounded by a thin tissue called the pleura. The pleura has both an inner and outer lining. The inner lining touches the lung and the outer lining faces an open cavity called the pleural space. Tumours that break through the inner lining of the pleura can spread into the pleural space and from there to other parts of the body.

Your pathologist will closely examine all the sections of the pleura under the microscope to see if any tumour cells have passed the inner lining of the pleural. The movement of tumour cells through the inner lining of the pleural is called pleural invasion. Pleural invasion is important because it increases the tumour stage (see Pathologic stage below) and is associated with a worse prognosis.

Has the tumour grown into organs outside of the lung?

The lung is surrounded by several organs including bones, muscles, diaphragm, heart, esophagus, and trachea. Large tumours can grow beyond the lung and into any of these surrounding organs. Invasion into another organ is important because it increases the pathologic tumour stage (pT) and is associated with a worse prognosis.

What does treatment effect mean?

Treatment effect is described in your report only if you received either chemotherapy or radiation therapy before surgery to remove the tumour. To determine the treatment effect, your pathologist will measure the amount of viable (living) tumour and express that number as a percentage of the original tumour. For example, if your pathologist finds 1 cm of viable tumour and the original tumour was 10 cm, the percentage of viable tumour is 10%.

What does lymphovascular invasion mean and why is it important?

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells were seen inside a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. The lymphatic vessels connect with small immune organs called lymph nodes that are found throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because cancer cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other parts of the body such as lymph nodes or the liver.

What is a margin and why are margins important?

In pathology, a margin is the edge of a tissue that is cut when removing a tumour from the body. The margins described in a pathology report are very important because they tell you if the entire tumour was removed or if some of the tumour was left behind. The margin status will determine what (if any) additional treatment you may require.

Most pathology reports only describe margins after a surgical procedure called an excision or resection has been performed to remove the entire tumour. For this reason, margins are not usually described after a procedure called a biopsy is performed to remove only part of the tumour. The number of margins described in a pathology report depends on the types of tissues removed and the location of the tumour. The size of the margin (the amount of normal tissue between the tumour and the cut edge) depends on the type of tumour being removed and the location of the tumour.

Pathologists carefully examine the margins to look for tumour cells at the cut edge of the tissue. If tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, the margin will be described as positive. If no tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, a margin will be described as negative. Even if all of the margins are negative, some pathology reports will also provide a measurement of the closest tumour cells to the cut edge of the tissue.

A positive (or very close) margin is important because it means that tumour cells may have been left behind in your body when the tumour was surgically removed. For this reason, patients who have a positive margin may be offered another surgery to remove the rest of the tumour or radiation therapy to the area of the body with the positive margin.

What are lymph nodes and why are they important?

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour to lymph nodes through small vessels called lymphatics. For this reason, lymph nodes are commonly removed and examined under a microscope to look for cancer cells. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to another part of the body such as a lymph node is called metastasis.

Lymph nodes from the neck, chest, and lungs may be removed at the same time as the tumour. These lymph nodes are divided into areas called stations. There are 14 different stations in the neck, chest, and lungs (see picture below).

If any lymph nodes were removed from your body, they will be examined under the microscope by a pathologist and the results of this examination will be described in your report. Most reports will include the total number of lymph nodes examined, where in the body the lymph nodes were found, and the number (if any) that contain cancer cells. If cancer cells were seen in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) will also be included.

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy is required.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

The pathologic stage for SCC of the lung is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

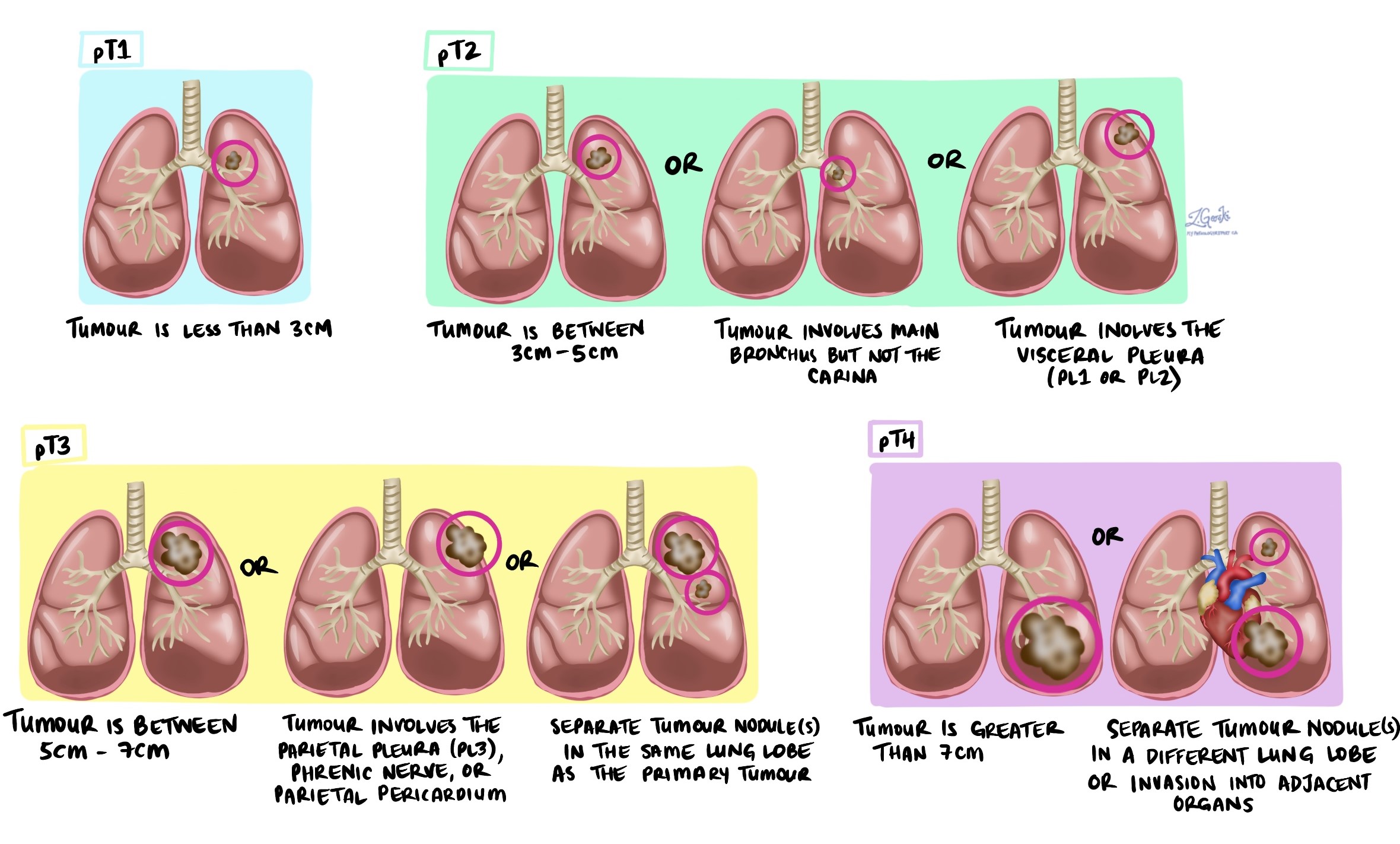

Tumour stage (pT) for squamous cell carcinoma of the lung

SCC is given a tumour stage between 1 and 4 based on the size of the tumour, the number of tumours found in the tissue examined, and whether the tumour has broken through the pleural or has spread to organs around the lungs.

Nodal stage (pN) for squamous cell carcinoma of the lung

SCC is given a nodal stage between 0 and 3 based on the presence or absence of cancer cells in a lymph node and the location of the lymph nodes that contain tumour cells.

- NX – No lymph nodes were sent for pathologic examination.

- N0 – No tumour cells were found in any of the lymph nodes examine

- N1 – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node from inside the lung or around the large airways leading into the lung. This stage includes stations 10 through 14.

- N2 – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node from the tissue in the middle of the chest and around the large airways. This stage includes stations 7 through 9.

- N3 – Tumour cells were found in the neck or in any lymph nodes on the side of the body opposite (contralateral) to the tumour. This stage includes stations 1 through 6.

About this article

This article was written by doctors to help you read and understand your pathology report. Contact us if you have any questions about this article or your pathology report. Read this article for a more general introduction to the parts of a typical pathology report.