by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

June 21, 2025

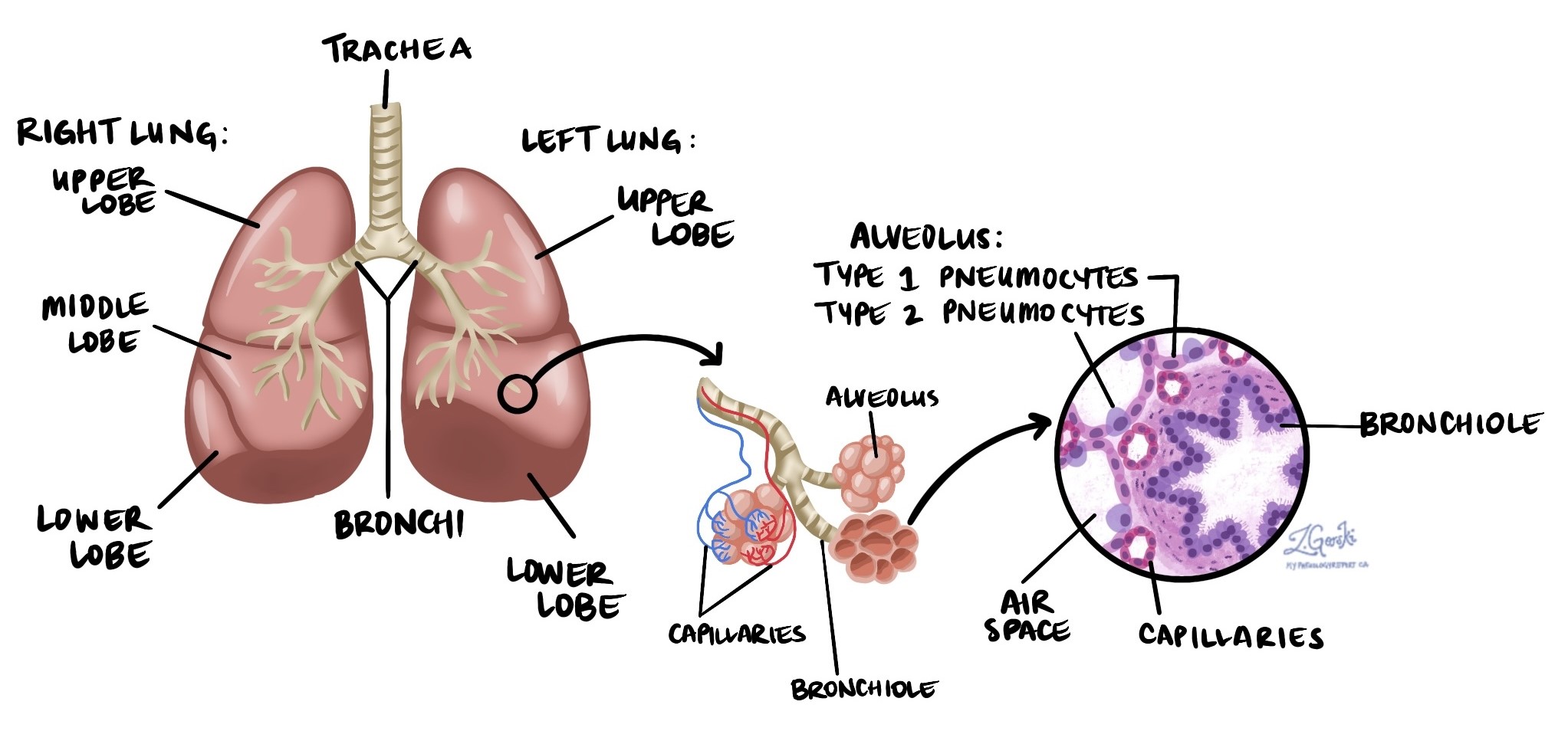

Non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma is a type of lung cancer. It belongs to a group called non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC). The term “non-keratinizing” means that this tumour does not produce large amounts of a protein called keratin. This makes it different from keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, which has large amounts of keratin. Non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma typically starts in the central parts of the lungs and is strongly linked to smoking.

What causes non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the lung?

The most common cause of non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the lung is smoking cigarettes for many years. Other factors include exposure to second-hand smoke, radon gas, asbestos, and other harmful chemicals in the environment or workplace.

What are the symptoms of non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the lung?

Common symptoms of non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma include:

-

A cough that does not go away or worsens over time.

-

Coughing up blood.

-

Chest pain or discomfort.

-

Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing.

If the tumour spreads (metastasizes) to other areas of the body, it can cause additional symptoms. For example, cancer cells in bones can cause bone pain or weaken the bone, leading to breaks known as pathologic fractures.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis is usually first suspected when your doctor performs imaging tests such as X-rays or CT scans of your chest. To confirm the diagnosis, a small sample of tissue is taken from the tumour in procedures called a biopsy or fine needle aspiration (FNA). The sample is examined under a microscope by a pathologist.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, your doctor may recommend surgery to remove the entire tumour. The type of surgery depends on the tumour’s size and location:

-

Wedge resection: Removing a small tumour located near the surface of the lung.

-

Lobectomy: Removing one entire lobe of the lung.

-

Pneumonectomy: Removing the entire lung (performed when the tumour is large or centrally located).

What does non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, this tumour is made up of large, dark blue cells. These cells appear blue because they contain very little keratin. Tumour cells also vary in shape and size. Pathologists refer to this variation as “pleomorphic.” Another common finding is the presence of numerous mitotic figures, indicating that the cells are rapidly dividing and creating new tumour cells.

What other tests may be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

Your pathologist may perform special tests called immunohistochemistry to confirm the type of tumour. These tests help distinguish non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma from other lung tumours that might look similar under the microscope.

The test results typically show:

-

p40: Positive (present in tumour cells).

-

CK5: Positive.

-

TTF-1: Negative (not present in tumour cells).

-

Chromogranin: Negative.

-

Synaptophysin: Negative.

Multiple tumours

Sometimes, more than one tumour can be found in the same lung. When this happens, each tumour is described separately.

There are two reasons why multiple tumours may be present:

-

Spread (metastasis): Cancer cells from the original tumour have spread to another part of the lung. This is likely if all tumours look the same under the microscope and are on the same side of your body. Smaller tumours are often referred to as “nodules.”

-

Separate tumours: The tumours developed independently. This is more likely if the tumours look different under the microscope. For example, one tumour might be non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, and another might be an adenocarcinoma. These are considered separate cancers, not metastatic spread.

Pleural invasion

The pleura is a thin layer of tissue that covers the lungs and lines the inner surface of the chest cavity.

It has two layers:

-

Visceral pleura: The layer attached directly to your lungs.

-

Parietal pleura: The layer lining the chest wall and diaphragm.

When tumour cells grow beyond the lung and invade the pleura, it is called pleural invasion. Pleural invasion is important because it affects both staging and prognosis:

-

Tumour stage: Tumours invading the pleura are considered more advanced. Pleural invasion increases the tumour’s T-stage in the TNM staging system.

-

Prognosis: Patients with pleural invasion generally have a worse prognosis because the cancer is more aggressive and likely to spread.

Lymphovascular invasion

Cancer cells can spread into tiny blood vessels or lymphatic channels, a process called lymphovascular invasion. Blood vessels carry blood throughout the body, while lymphatic channels carry lymph fluid, which plays a crucial role in immune function. When tumour cells enter these channels, they can spread to other parts of the body, such as lymph nodes, the liver, or bones. Finding lymphovascular invasion means a higher risk of cancer spreading.

Margins

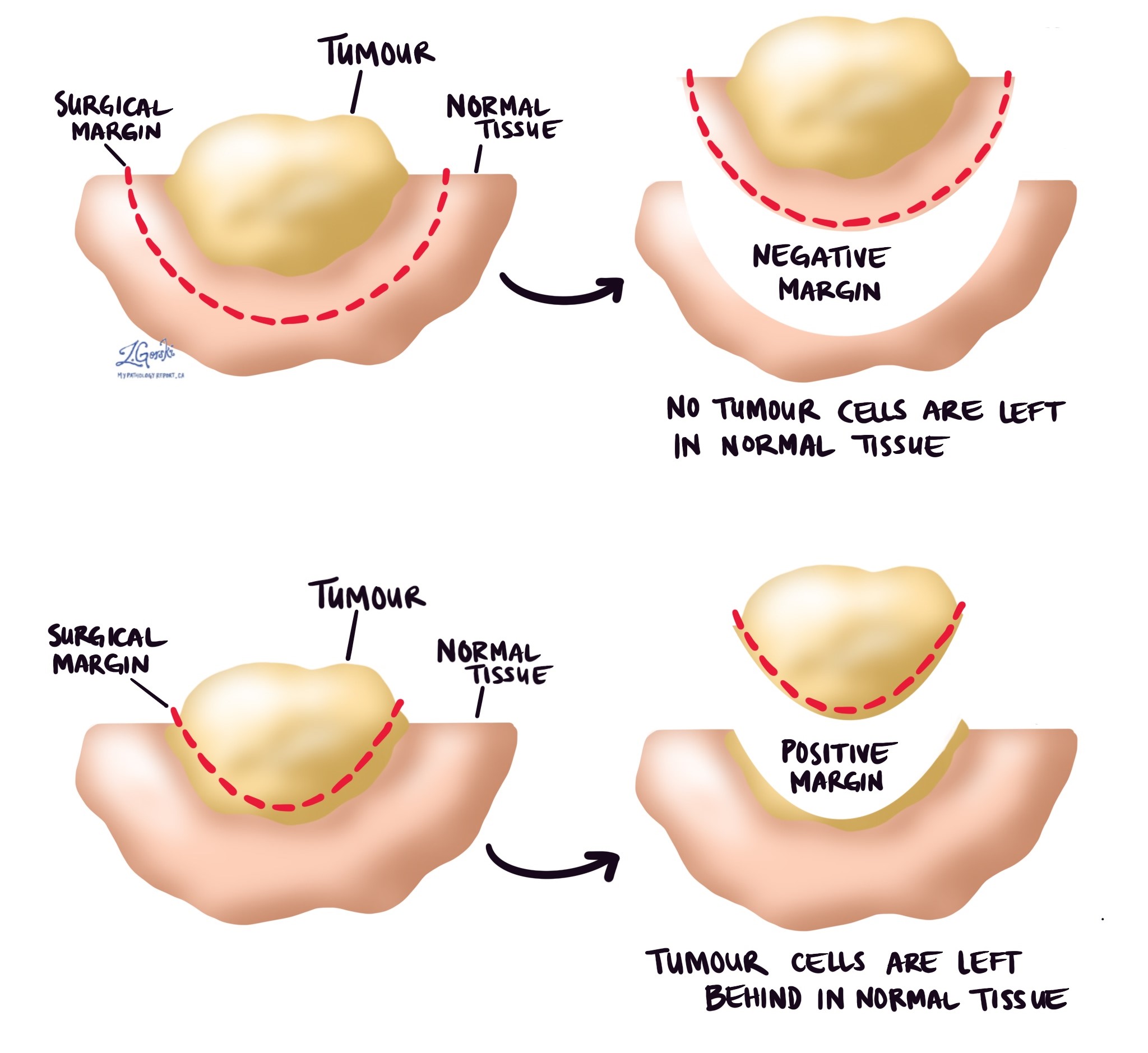

In pathology, a margin refers to the edge of tissue removed during surgery to remove a tumour. After lung surgery, pathologists carefully examine all of these tissue edges under a microscope to determine if the tumour has been completely removed.

Margins assessed in lung cancer surgeries typically include:

-

Bronchial margin – This is where the surgeon cuts through the airway.

-

Vascular margin – These are the areas where large blood vessels near the tumour are cut.

-

Parenchymal margin – This margin includes the edge of lung tissue around the tumour.

-

Pleural margin – The pleura is a thin lining surrounding the lung, and this margin is examined to determine if the tumour grows close to or through this lining.

Margins can be described in two ways:

-

Negative margin – No cancer cells are seen at any cut edge. This indicates that the tumour has likely been entirely removed, which is the goal of surgery.

-

Positive margin – Cancer cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue. A positive margin means there could still be tumour cells remaining in your body. Patients with a positive margin may require additional treatments, such as a second surgery or radiation therapy, to remove any remaining tumour cells and reduce the risk of recurrence.

The status of the margins helps your doctor determine the need for additional treatment and plays an important role in predicting the likelihood of the tumour growing back.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped organs that play an essential role in the immune system. They are connected throughout the body by small channels called lymphatic vessels. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour through these lymphatic vessels and into nearby lymph nodes—a process called lymph node metastasis.

Lymph nodes in the lungs and chest are grouped into specific areas, known as lymph node stations. There are 14 different lymph node stations, each with a specific location:

-

Station 1: Lower cervical, supraclavicular, and sternal notch lymph nodes.

-

Station 2: Upper paratracheal lymph nodes.

-

Station 3: Prevascular and retrotracheal lymph nodes.

-

Station 4: Lower paratracheal lymph nodes.

-

Station 5: Subaortic (aortopulmonary window) lymph nodes.

-

Station 6: Para-aortic lymph nodes (near the ascending aorta or phrenic nerve).

-

Station 7: Subcarinal lymph nodes (below the carina, where the trachea splits into bronchi).

-

Station 8: Paraesophageal lymph nodes (alongside the esophagus below the carina).

-

Station 9: Pulmonary ligament lymph nodes.

-

Station 10: Hilar lymph nodes (at the lung hilum, where airways enter the lung).

-

Station 11: Interlobar lymph nodes (between lung lobes).

-

Station 12: Lobar lymph nodes (within lung lobes).

-

Station 13: Segmental lymph nodes (within lung segments).

-

Station 14: Subsegmental lymph nodes (within smaller lung subsegments).

If lymph nodes are removed during surgery, a pathologist carefully examines them under a microscope to see if they contain cancer cells. The pathology report typically includes:

-

The total number of lymph nodes examined.

-

The locations (stations) of the lymph nodes examined.

-

The number of lymph nodes containing cancer cells.

-

The size of the largest group of cancer cells (often called a “focus” or “deposit”).

Lymph node examination provides important information that helps your doctor determine the cancer’s pathologic nodal stage (pN). It also helps predict the likelihood that cancer cells may have spread to other parts of the body, guiding decisions about additional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

Pathologists use the TNM staging system to determine how advanced the cancer is and to help guide treatment decisions.

-

Tumour (T) stage: Based on the size of the tumour and any invasion of surrounding tissues.

-

Node (N) stage: Based on the number of lymph nodes examined and the number that contain cancer cells.

-

Metastasis (M) stage: Based on the spread of cancer cells to distant parts of the body such as bones or the brain.

Each of these categories is given a number; higher numbers mean more advanced disease.

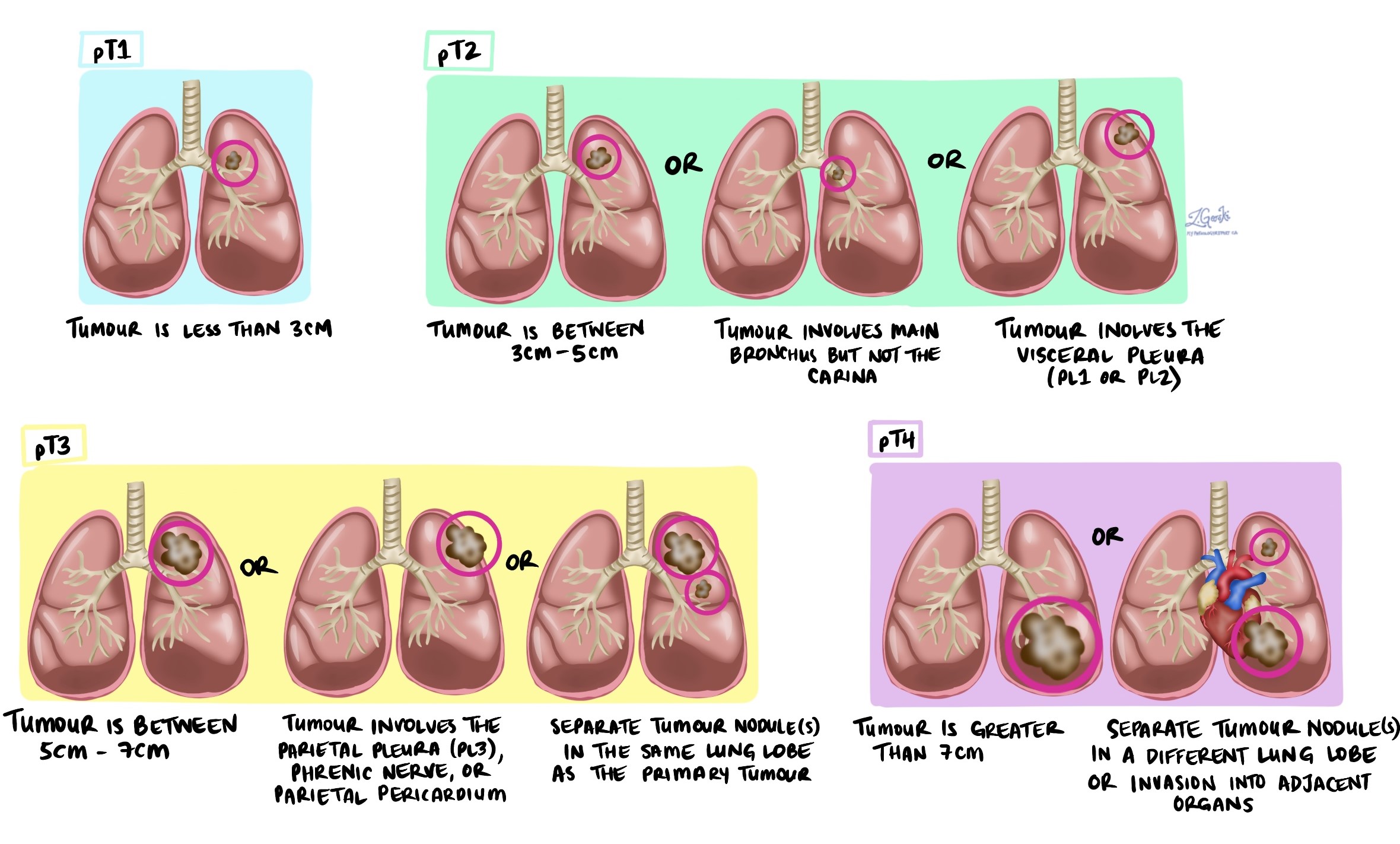

Tumour stage (pT)

-

T1: Tumour is 3 cm or smaller.

-

T2: Tumour is larger than 3 cm but not larger than 5 cm, or it has invaded the visceral pleura or main airways.

-

T3: Tumour is larger than 5 cm but not larger than 7 cm or has grown into nearby tissues.

-

T4: Tumour is larger than 7 cm or has invaded nearby organs such as the heart or esophagus.

Nodal stage (pN)

-

NX: Lymph nodes were not examined.

-

N0: No cancer cells in lymph nodes.

-

N1: Cancer cells in lymph nodes inside the lung or near airways (stations 10–14).

-

N2: Cancer cells in lymph nodes in the central chest near the airways (stations 7–9).

-

N3: Cancer cells in lymph nodes on the opposite side of the chest or in the lower neck (stations 1–6).

Metastatic stage (pM)

-

M0: No distant spread.

-

M1: Cancer has spread to distant parts of the body.

-

MX: Unable to determine if distant spread has occurred.

What is the prognosis for a person with non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the lung?

The prognosis for non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the lung depends on several important factors.

These include:

-

Stage of the tumour – Smaller tumours that have not spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body have a better prognosis than larger tumours or those that have spread.

-

Lymph node involvement – Tumours that have spread to nearby lymph nodes usually have a less favourable prognosis.

-

Metastatic spread – If cancer cells have spread to distant parts of the body, such as the bones or brain, the prognosis is usually poorer.

-

Margins – Completely removing the tumour with negative margins (no cancer cells at the cut edge) improves the prognosis. Positive margins may require additional treatment and can increase the risk of recurrence.

-

Pleural and lymphovascular invasion – Tumours that have invaded the pleura or show lymphovascular invasion typically have a higher risk of recurrence and a less favourable outcome.

Your doctor will carefully consider all of these factors when discussing your prognosis and planning your treatment.

In general, detecting non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma early, when the tumour is still small and localized, is associated with the best outcomes. More advanced cancers often require more aggressive treatments and have a less favourable prognosis. Regular follow-up and adherence to your treatment plan are crucial to achieving the best possible outcome.

Questions for your doctor

-

Is the tumour completely removed?

-

Are the lymph nodes affected?

-

Do I need additional treatments like chemotherapy or radiation therapy?

-

How often will I need follow-up tests?

-

Should my family and I have genetic testing?

-

What lifestyle changes can help my recovery?

-

Am I eligible for any clinical trials or new therapies?