by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD

February 5, 2024

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a type of esophageal cancer. The tumour starts from specialized squamous cells that cover the inside of the esophagus. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma is one of the most common types of esophageal cancer worldwide.

This article will help you understand your diagnosis and pathology report for invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus.

What causes invasive squamous cell carcinoma in the esophagus?

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma in the esophagus is associated with both long-term alcohol use and smoking although a variety of injuries and chemicals can also cause this kind of cancer.

What are the symptoms of invasive squamous cell carcinoma in the esophagus?

Symptoms of invasive squamous cell carcinoma in the esophagus include difficulty or pain when swallowing food. This is sometimes described as the sensation of food getting “stuck” after swallowing. The symptoms are worse initially with solids but progress to both solids and liquids.

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma starts from squamous cells normally found in the epithelium, a thin layer of tissue that covers the inside surface of the larynx. It commonly develops from a precancerous condition dysplasia. In dysplasia, the abnormal squamous cells are located entirely within the epithelium. Over time, the abnormal cells break out of the epithelium, spreading into the underlying stroma. This process is called invasion and it signals the transition from dysplasia to invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Your pathology report for invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus

The information found in your pathology report for invasive squamous cell carcinoma in the esophagus will depend on the procedure performed. For small procedures such as a biopsy, your report may only include the diagnosis, the grade (for example well differentiated), and the depth of invasion (how far the tumour has spread from its starting point on the inside surface of the esophagus). The results of additional biomarker or molecular tests may also be described. After the tumour is removed fully, additional information such as the size of the tumour and the assessment of margins may also be described. This information will be described in more detail in the sections below.

Tumour grade

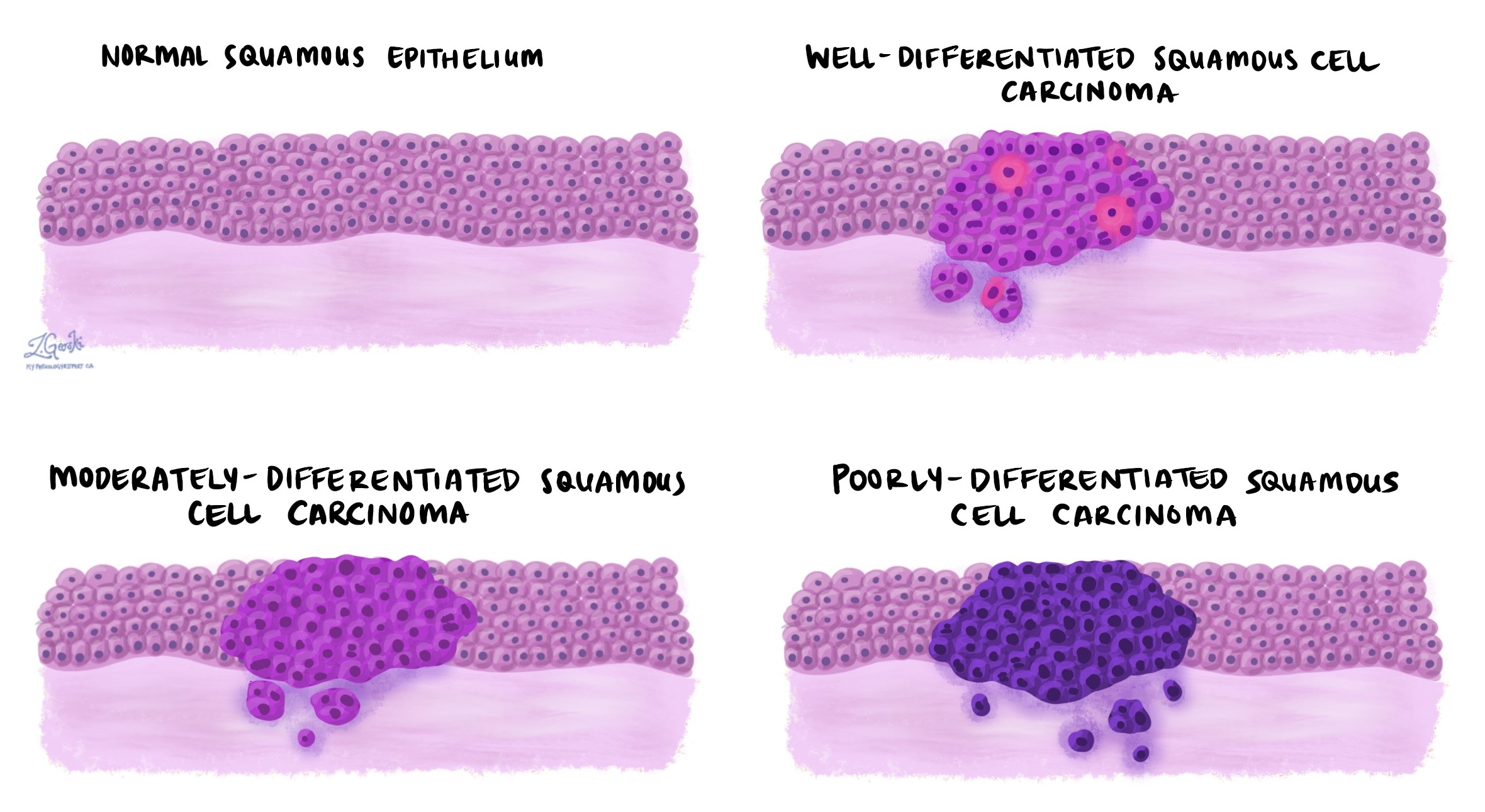

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is divided into three grades – well differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated. The grade is based on how much the tumour cells look like the squamous cells normally found in the epithelium on the inside surface of the esophagus and it can only be determined after the tumour is examined under the microscope.

The grade is important because higher-grade tumours (specifically, poorly differentiated tumours) behave more aggressively and are more likely to regrow after treatment and metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes or other parts of the body.

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is graded as follows:

- Well differentiated – Well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is made up of tumour cells that look almost the same as normal squamous cells.

- Moderately differentiated – Moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is made up of tumour cells that look different from normal squamous cells, however, they can still be recognized as squamous cells.

- Poorly differentiated – Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is made up of tumour cells that look very little like normal squamous cells. These cells can look so abnormal that your pathologist may need to order an additional test such as immunohistochemistry to confirm the diagnosis.

Depth of invasion and pathologic tumour stage (pt)

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma starts in a thin layer of tissue called the epithelium on the inside surface of the esophagus. As the tumour grows, the cancer cells will spread or invade into deeper layers of tissue such as the muscularis mucosae, submucosa, muscularis propria, or adventitia. A very large tumour can spread beyond the esophagus into surrounding organs such as the trachea. Pathologists use the term depth of invasion to describe how far the tumour has spread from the epithelium into the deeper layers of tissue and the depth of invasion is important because it is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT) for invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus.

Invasion of the muscularis mucosa

The muscularis mucosa is a thin layer of muscle just under the epithelium on the inside surface of the esophagus. Invasion of the muscularis mucosa indicates a pathologic tumour stage of at least pT1a.

Invasion of the submucosa

The submucosa is a thin layer of connective tissue just under the muscularis mucosa. Tumours of the esophagus that invade the submucosa come in contact with more blood vessels and lymphatic channels. As a result, these tumours are more likely to metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes and other parts of the body. Invasion of the submucosa indicates a pathologic tumour stage of at least pT1b.

Invasion of the muscularis propria

The muscularis propria is a thick layer of muscle in the middle of the wall of the esophagus. Tumours of the esophagus that invade the muscularis propria are usually quite large and tend to behave more aggressively compared to tumours that only involve the muscularis mucosa or submucosa. Invasion of the muscularis propria indicates a pathologic tumour stage of at least pT2.

Invasion of the adventitia

The adventitia is a thin layer of tissue on the outside surface of the esophagus. Tumours of the esophagus that invade the adventitia are much more likely to metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes and other parts of the body. Tumours that involve the adventitia are also more likely to spread directly to nearby organs such as the trachea which can make them very difficult to remove surgically. Invasion of the adventitia indicates a pathologic tumour stage of at least pT3.

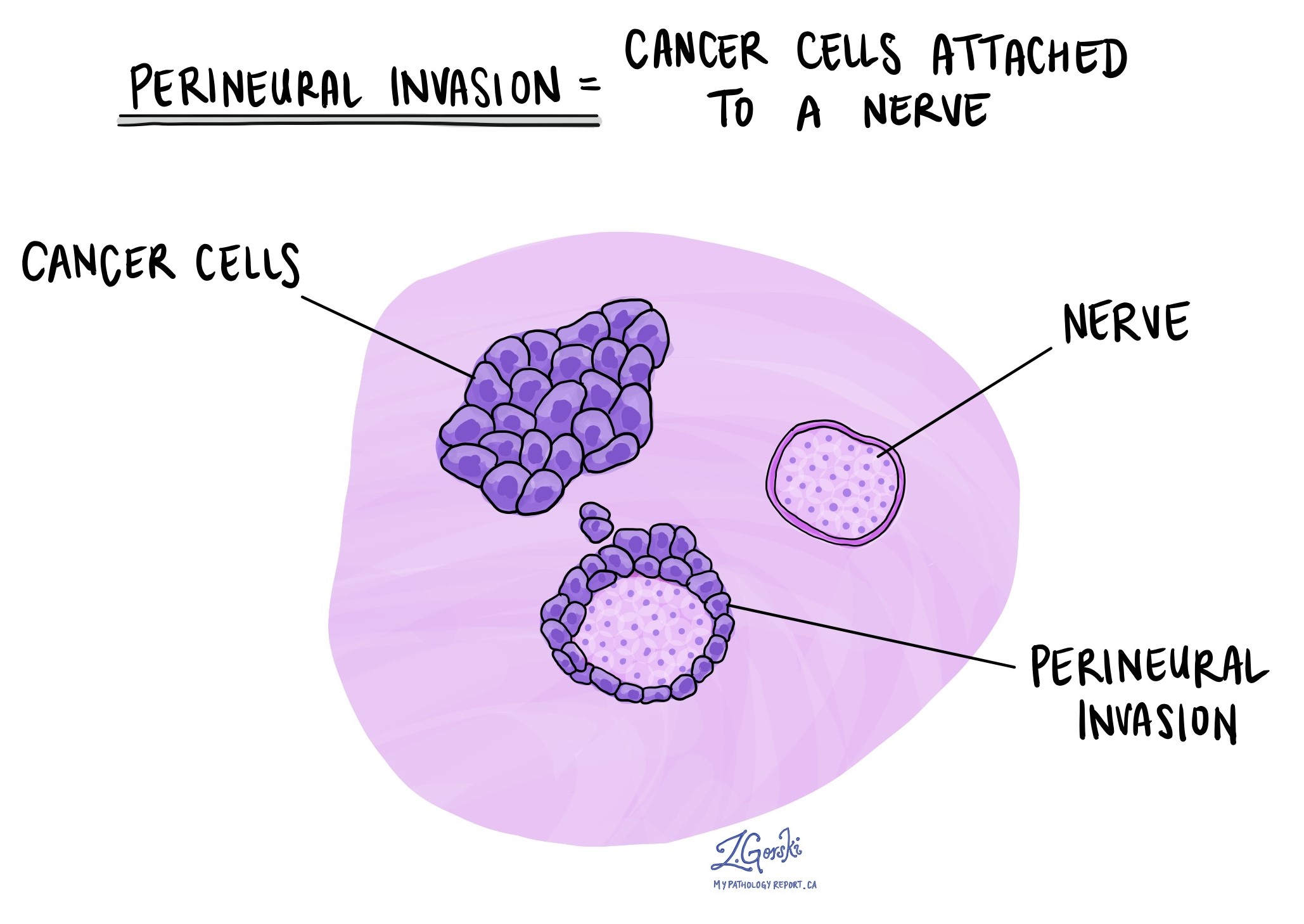

Perineural invasion

Pathologists use the term “perineural invasion” to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that specifically refers to cancer cells found inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. The presence of perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic channel. Blood vessels, thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, contrast with lymphatic channels, which carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic channels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes, scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it enables cancer cells to spread to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the lungs, via the blood or lymphatic vessels.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour to lymph nodes through small lymphatic vessels. For this reason, lymph nodes are commonly removed and examined under a microscope to look for cancer cells. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to another part of the body such as a lymph node is called a metastasis.

Cancer cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour although lymph nodes far away from the tumour can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are only typically removed if they are enlarged and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancer cells in the lymph node.

A neck dissection is a surgical procedure performed to remove lymph nodes from the neck. The lymph nodes removed usually come from different areas of the neck and each area is called a level. The levels in the neck include 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Your pathology report will often describe how many lymph nodes were seen in each level sent for examination. Lymph nodes on the same side as the tumour are called ipsilateral while those on the opposite side of the tumour are called contralateral.

If any lymph nodes were removed from your body, they will be examined under the microscope by a pathologist and the results of this examination will be described in your report. “Positive” means that cancer cells were found in the lymph node. “Negative” means that no cancer cells were found. If cancer cells are found in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) may also be included in your report. Extranodal extension means that the tumour cells have broken through the capsule on the outside of the lymph node and have spread into the surrounding tissue.

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy is required.

Margins

In pathology, a margin refers to the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure like an excision or resection, aimed at removing the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are present at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was fully removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

For esophagectomy specimens where an entire segment of the esophagus has been removed, the margins will include:

- Proximal margin – This margin is located near the upper portion of the esophagus closer to the mouth.

- Distal margin – This margin is located near the lower portion of the esophagus. The distal margin can be in the esophagus or the stomach.

- Radial margin – This is the tissue around the outside of the esophagus.

For endoscopic resections where only a small piece of the inside of the esophagus has been removed, the margins will include:

- Mucosal margin – This is the tissue that lines the inner surface of the esophagus.

- Deep margin – This tissue is inside the wall of the esophagus. It is located below the tumour.

Pathologic stage

The pathologic stage for invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT)

The pathologic tumour stage (pT) for invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is based on the tumour depth of invasion or how far the tumour has spread from the epithelium on the inside surface of the esophagus into the layers of tissue below. The tumour stage can usually only be determined after the entire tumour has been surgically removed.

- T1a – The tumour cells have not spread past the muscularis mucosa on the inside surface of the esophagus.

- T1b – The tumour cells have entered the submucosa.

- T2 – The tumour cells have entered the muscularis propria in the middle of the wall.

- T3 – The tumour cells are in the adventitia on the outer surface of the esophagus.

- T4 – The tumour cells have spread beyond the esophagus into surrounding organs or tissues such as the lungs or aorta.

Nodal stage (pN)

The pathologic nodal stage (pN) for invasive squamous cell of the esophagus is based on the number of lymph nodes that contain tumour cells. If no lymph nodes are submitted for pathological examination, the nodal stage cannot be determined and the nodal stage is listed as NX.

- N0 – No tumour cells are seen in any lymph nodes examined.

- N1 – Tumour cells are seen in one or two lymph nodes.

- N2 – Tumour cells are seen in three to six lymph nodes.

- N3 – Tumour cells are seen in more than six lymph nodes.

About this article

This article was written by doctors to help you read and understand your pathology report. Contact us if you have any questions about this article or your pathology report. Read this article for a more general introduction to the parts of a typical pathology report.