by Emily Goebel, MD FRCPC

April 28, 2023

What is squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina?

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of cancer in the vagina. The tumour starts from specialized squamous cells that cover the inside surface of the vagina.

What causes squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina?

The most common cause of squamous cell carcinoma in the vagina is an infection of the squamous cells by human papillomavirus (HPV). There are many types of HPV virus and most cases of squamous cell carcinoma are caused by the high-risk types HPV-16 and HPV-18.

How is the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina made?

The diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina is usually made after a small tissue sample is removed in a procedure called a biopsy. The entire tumour is usually then removed in a procedure called an excision or resection.

What does it mean if squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina is described as well, moderately, or poorly differentiated?

Pathologists divide squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina into three grades based on how much the tumour cells look like normal squamous cells when examined under the microscope. The grade is important because higher-grade tumours (moderately and poorly differentiated tumours) behave in a more aggressive manner and are more likely to spread to other parts of the body.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina is graded as follows:

- Well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina – A well differentiated tumour (grade 1) is made up of tumour cells that look almost the same as normal squamous cells.

- Moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina – A moderately differentiated tumour (grade 2) is made up of tumour cells that clearly look different from normal squamous cells, however, they can still be recognized as squamous cells.

- Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina – A poorly differentiated tumour (grade 3) is made up of tumour cells that look very little like normal squamous cells. These cells can look so abnormal that your pathologist may need to order an additional test such as immunohistochemistry to confirm the diagnosis.

What is p16 and why do pathologists test for it?

Cells infected with high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV) produce large amounts of a protein called p16. Your pathologist may perform a test called immunohistochemistry to look for p16 inside the tumour cells. This will confirm the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma and rule out other conditions that can look like squamous cell carcinoma under the microscope. Almost all cases of squamous cell carcinoma in the vagina are positive for p16.

Why is the tumour size important?

After the entire tumour has been removed, your pathologist will measure it in three dimensions and the largest dimension will be described in your pathology report. The size of the tumour is important because it is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

What is tumour extension?

Pathologists use the term tumour extension to describe how far the tumour cells have spread from the original location where the tumour started in the vagina into surrounding organs and tissues such as the bladder and rectum. Tumour extension can only be determined after the entire tumour has been removed. For this reason, tumour extension is usually not described in the pathology report after a small tissue sample such as a biopsy. Tumour extension is important because it is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

What does lymphovascular invasion mean and why is it important?

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells were seen inside a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. The lymphatic vessels connect with small immune organs called lymph nodes that are found throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because cancer cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other parts of the body such as lymph nodes or the lungs.

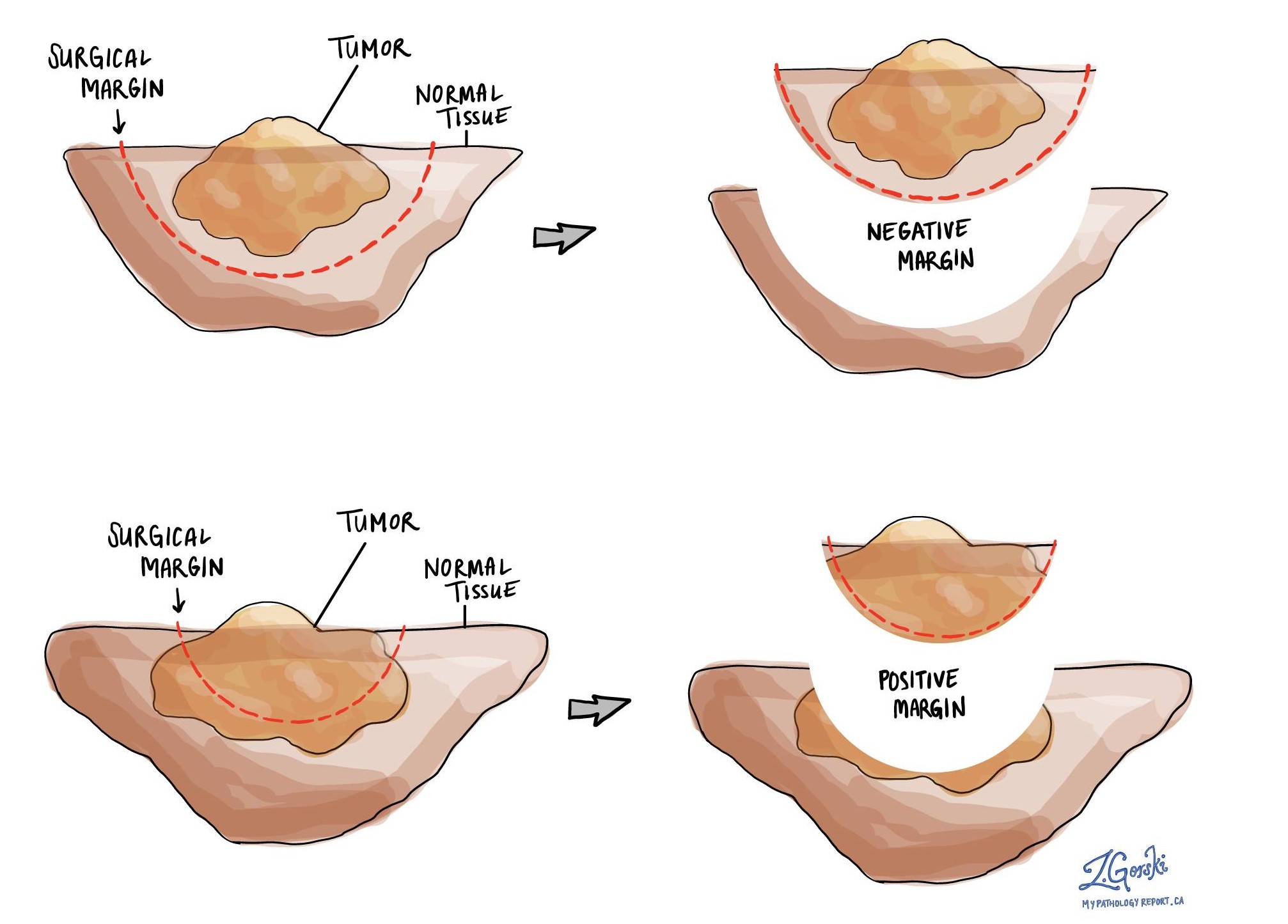

What is a margin and why are margins important?

A margin is any tissue that was cut by the surgeon in order to remove the tumour from your body. Whenever possible, surgeons will try to cut tissue outside of the tumour to reduce the risk that any tumour cells will be left behind after the tumour is removed.

Your pathologist will carefully examine all the margins in your tissue sample to see how close the tumour cells are to the edge of the cut tissue. Margins will only be described in your report after most or all of the tumour has been removed.

A negative margin means there were no tumour cells at the very edge of the cut tissue. If all the margins are negative, most pathology reports will say how far the closest tumour cells were to a margin. The distance is usually described in millimetres. A margin is considered positive when there are tumour cells at the very edge of the cut tissue. If HSIL is seen at the margin it will also be described in your report. A positive margin increases the risk that the tumour will grow back in that location.

What are lymph nodes?

Lymph nodes are small immune organs located throughout the body. Tumour cells can spread from the tumour to a lymph node through lymphatic channels located in and around the tumour (see Lymphovascular invasion above). The movement of tumour cells from the tumour to a lymph node is called lymph node metastasis.

Lymph nodes are not typically removed for squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. However, if lymph nodes are removed your pathologist will carefully examine each one of them for tumour cells. Lymph nodes that contain tumour cells are often called positive while those that do not contain any tumour cells are called negative. Most reports include the total number of lymph nodes examined and the number, if any, that contain tumour cells. The examination of lymph nodes is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN).

Pathologic stage (pTNM) for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina

The pathologic stage for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system originally created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT) for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina

Squamous cell carcinoma is given a tumour stage between 1 and 4.

Your pathologist will look for two features to determine the tumour stage:

- The size of the tumour.

- How far the tumour has spread into nearby tissues including surrounding soft tissue, bladder or rectum.

Nodal stage (pN) for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina

Squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina is given a nodal stage of 0 or 1 based on the presence or absence of cancer cells in a lymph node. If no cancer cells are seen in any of the lymph nodes examined, the nodal stage is N0. Lymph nodes with isolated tumour cells are also given a nodal stage of N0. If no lymph nodes are submitted for pathological examination, the nodal stage cannot be determined and the nodal stage is listed as NX.

Metastatic stage (pM) for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina

Squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina is given a metastatic stage of 0 or 1 based on the presence of cancer cells at a distant site in the body (for example the lungs). The metastatic stage can only be assigned if tissue from a distant site is submitted for pathological examination. Because this tissue is rarely present, the metastatic stage cannot be determined and is listed as MX.