by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

May 13, 2024

Widely invasive oncocytic carcinoma is a type of thyroid cancer. It is called “widely invasive” because groups of cancer cells are found throughout the normal thyroid gland. This type of cancer is made up of large oncocytic cells, also known as Hurthle cells.

How is this diagnosis made?

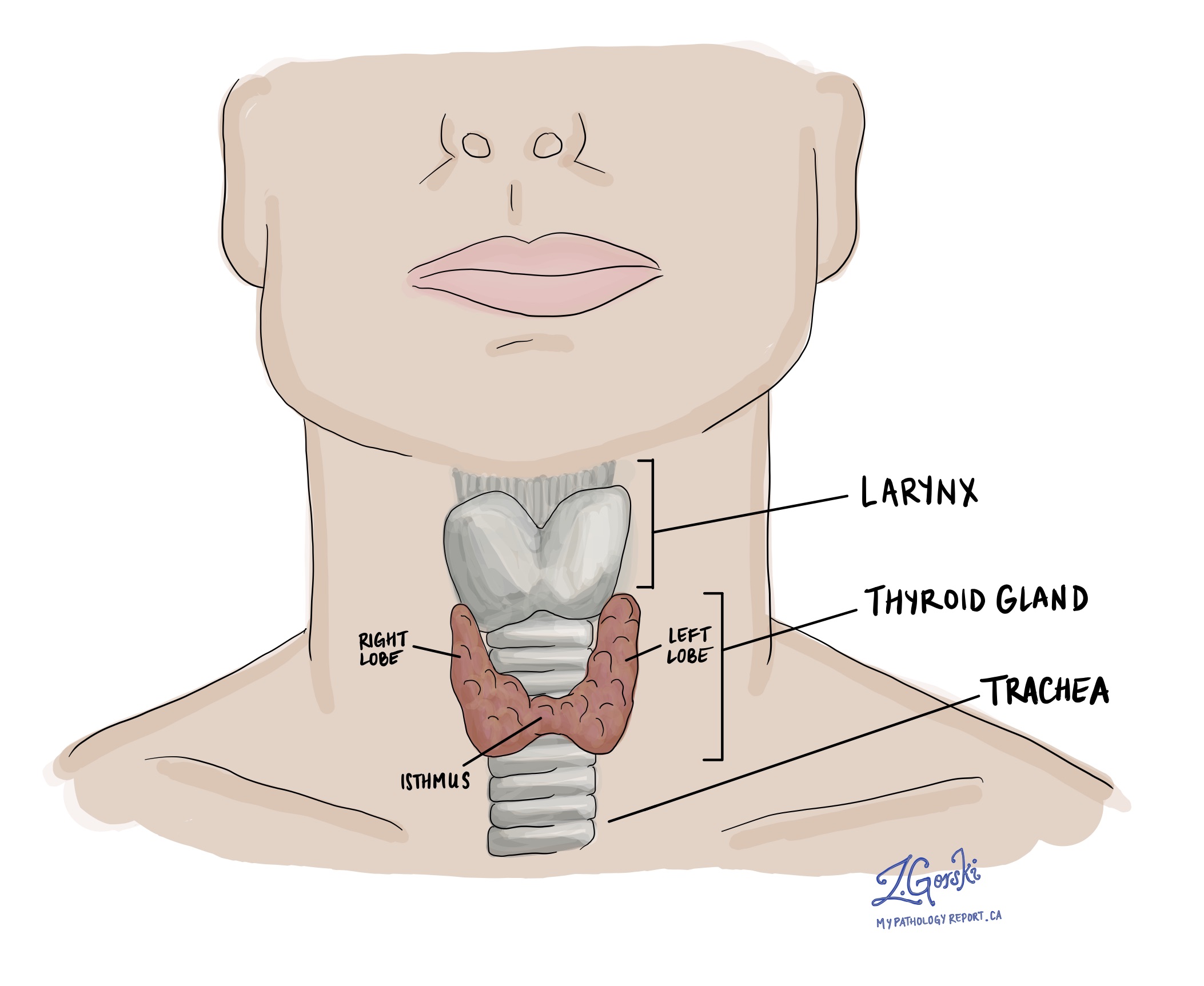

The diagnosis of widely invasive oncocytic carcinoma can only be made after the entire tumour is removed and sent to a pathologist for examination. This usually involves surgically removing one lobe of the thyroid gland, although sometimes the entire thyroid gland is removed. The diagnosis cannot be made after a less invasive procedure called a fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB).

What makes an oncocytic cell carcinoma widely invasive?

Oncocytic cell carcinoma is called “widely invasive” when the cancer cells have spread throughout the normal thyroid gland. In contrast, the cancer cells in a related type of cancer called minimally invasive oncocytic carcinoma are mostly separated from the normal thyroid gland by a thin layer of tissue called a tumour capsule.

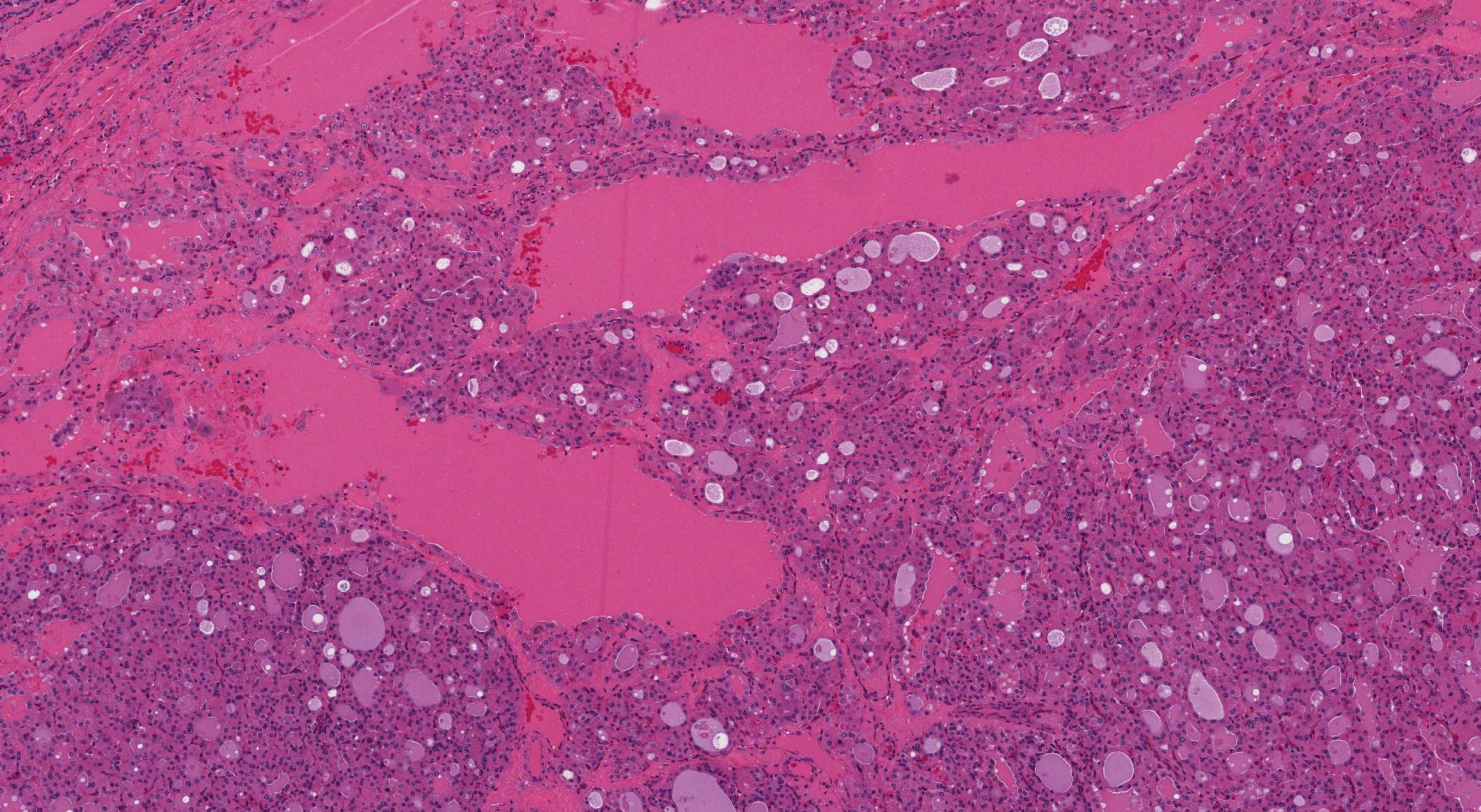

Microscopic features

When examined under the microscope, the tumour comprises large pink oncocytic cells. The cells appear pink because the cytoplasm (body of the cell) is full of a cellular part called mitochondria. Oncocytic cells also have a large round nucleus (the part of the cell that holds the genetic material) and a prominent central nucleolus (a clump of genetic material in the middle of the nucleus). The oncocytic cells can connect together to form small round structures called follicles, or they may be in large groups that pathologists describe as a ‘solid pattern’.

Tumour size

After the entire tumour is removed, it will be measured, and its size will be included in your pathology report. Tumour size is important because it determines the pathologic tumour stage (pT) and because larger tumours are more likely to spread to other parts of the body.

Vascular invasion (angioinvasion)

Vascular invasion (also known as angioinvasion) in the context of widely invasive oncocytic carcinoma of the thyroid gland refers to the spread of cancer cells into blood vessels outside the tumour. Vascular invasion is a marker of more aggressive behaviour and has important implications for the prognosis and management of the cancer.

Importance of vascular invasion:

- Metastatic potential: Vascular invasion increases the risk of cancer cells spreading to distant sites in the body through the bloodstream. This can lead to the formation of metastases, especially in organs like the lungs and bones, which are common sites for thyroid cancer metastasis.

- Prognosis: The presence of vascular invasion is generally associated with a poorer prognosis. It indicates that the cancer is more aggressive and capable of spreading to distant parts of the body.

- Treatment decisions: Identifying vascular invasion can influence treatment decisions. For instance, it may lead to the use of higher doses of radioactive iodine or the inclusion of systemic therapies to address potential metastatic disease.

- Follow-up and monitoring: Given their higher risk profile, patients with evidence of vascular invasion may require closer follow-up and more intensive monitoring for recurrence or spread of the disease.

Lymphatic invasion

Lymphatic invasion in the context of widely invasive oncocytic carcinoma of the thyroid gland refers to the infiltration and spread of cancer cells into the lymphatic system. Cancer cells that enter the lymphatic system can travel to lymph nodes. However, unlike vascular invasion, lymphatic invasion is not typically associated with more aggressive disease or worse prognosis.

Extrathyroidal extension

Extrathyroidal extension (ETE) refers to the spread of cancer cells beyond the thyroid gland into surrounding tissues. It is an important prognostic factor in thyroid cancer, as it can significantly influence both the staging and management of the disease.

Extrathyroidal extension is classified into two types based on the extent of the spread:

- Microscopic extrathyroidal extension: This form of extension is only visible under a microscope and indicates that the cancer has spread just beyond the thyroid capsule but cannot be seen with the naked eye. It may involve minimal infiltration into surrounding soft tissues.

- Macroscopic (or gross) extrathyroidal extension: This type is visible to the naked eye or detectable during surgery. It involves more obvious and extensive invasion into neighbouring structures such as muscles, trachea, esophagus, or major blood vessels.

Extrathyroidal extension is important for the following reasons:

- Prognosis: Macroscopic (gross) extrathyroidal extension is associated with a worse prognosis. It suggests a more aggressive cancer that is more likely to recur and metastasize.

- Staging: Extrathyroidal extension impacts the staging of thyroid cancer. For instance, in the TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) classification system used for thyroid cancer, macroscopic extrathyroidal extension results in a higher pathologic tumour stage (pT).

- Treatment and follow-up: The presence of macroscopic (gross) extrathyroidal extension might lead to more aggressive treatment strategies and closer follow-up in order to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Margins

A margin is any tissue that has to be cut by the surgeon in order to remove the thyroid gland from your body. A margin is considered positive when there are cancer cells at the very edge of the cut tissue. A negative margin means there were no cancer cells seen at the cut edge of the tissue.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour to lymph nodes through small lymphatic vessels. For this reason, lymph nodes are commonly removed and examined under a microscope to look for cancer cells. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to another part of the body such as a lymph node is called a metastasis.

Cancer cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour, although lymph nodes far away from the tumour can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are only typically removed if they are enlarged and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancer cells in the lymph node.

A neck dissection is a surgical procedure performed to remove lymph nodes from the neck. The lymph nodes removed usually come from different neck areas, and each area is called a level. The levels in the neck include 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Your pathology report will often describe how many lymph nodes were seen in each level sent for examination. Lymph nodes on the same side as the tumour are called ipsilateral, while those on the opposite side of the tumour are called contralateral.

If any lymph nodes were removed from your body, they will be examined under the microscope by a pathologist, and the results of this examination will be described in your report. “Positive” means that cancer cells were found in the lymph node. “Negative” means that no cancer cells were found. If cancer cells are found in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) may also be included in your report. Extranodal extension means that the tumour cells have broken through the capsule on the outside of the lymph node and have spread into the surrounding tissue.

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information determines the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment, such as radioactive iodine, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy, is required.

Pathologic stage

The pathologic stage for widely invasive oncocytic carcinoma is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system originally created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT)

Widely invasive oncocytic carcinoma is given a tumour stage between 1 and 4 based on its size and the presence of cancer cells outside of the thyroid.

- T1 – The tumour is less than or equal to 2 cm, and the cancer cells do not extend beyond the thyroid gland.

- T2 – The tumour is greater than 2 cm but less than or equal to 4 cm, and the cancer cells do not extend beyond the thyroid gland.

- T3 – The tumour is greater than 4 cm OR the cancer cells extend into the muscles outside of the thyroid gland.

- T4 – The cancer cells extend to structures or organs outside the thyroid gland, including the trachea, larynx, or esophagus.

Nodal stage (pN)

Widely invasive oncocytic carcinoma is given a nodal stage of 0 or 1 based on the presence or absence of cancer cells in a lymph node and the location of the involved lymph nodes.

- N0 – No cancer cells were found in any of the lymph nodes examined.

- N1a – Cancer cells were found in one or more lymph nodes from levels 6 or 7.

- N1b – Cancer cells were found in one or more lymph nodes from levels 1 through 5.

- NX – No lymph nodes were sent to pathology for examination.