By Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

November 23, 2025

Non-ampullary adenocarcinoma of the duodenum is a type of cancer that starts in the gland-forming cells that line the inside surface of the duodenum, which is the first part of the small intestine located just beyond the stomach. The duodenum plays an important role in digestion by mixing food with stomach acid, bile, and pancreatic enzymes. In non-ampullary adenocarcinoma, the cancer begins away from the ampulla of Vater, which is the area where the bile duct and pancreatic duct drain into the intestine. Because non-ampullary tumors begin outside this region, they often grow silently at first and may not cause noticeable symptoms until they become larger.

Like other adenocarcinomas of the digestive tract, non-ampullary duodenal adenocarcinoma can invade deeper layers of the intestinal wall and spread to nearby lymph nodes or other organs as it progresses. Early detection can be difficult because the duodenum is located deep in the abdomen and early-stage tumors often produce few or nonspecific symptoms.

Anatomy of the duodenum

The duodenum is the shortest segment of the small intestine and connects the stomach to the jejunum. It curves around the pancreas and receives bile and pancreatic enzymes that help digest food. The duodenal lining contains many small glands that absorb nutrients and neutralize stomach acid. Non-ampullary tumors arise away from the ampulla, usually on the opposite wall or in areas not directly influenced by bile and pancreatic drainage. This distinction is important because non-ampullary tumors behave differently and are staged differently from ampullary carcinomas.

What are the symptoms of non-ampullary adenocarcinoma of the duodenum?

Early-stage nonampullary adenocarcinomas often produce no symptoms. As the tumor enlarges, people may experience abdominal pain, especially in the upper abdomen. Slow bleeding from the tumor can lead to occult blood loss, which causes anemia, fatigue, light-headedness, or shortness of breath. Some tumors cause nausea, vomiting, or discomfort after eating as they begin to narrow or block the intestinal passageway.

Because the tumor is non-ampullary, jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes) is less common than in ampullary cancers. However, larger tumors may still cause weight loss, changes in appetite, or abdominal distension. These nonspecific symptoms often lead to imaging or endoscopic exams, which are typically required to detect the tumor.

What risk factors are associated with non-ampullary duodenal adenocarcinoma?

Several factors increase the likelihood of developing this cancer. Conditions that cause long-term inflammation in the small intestine, such as Crohn’s disease or celiac disease, increase risk. Lifestyle factors such as smoking, heavy alcohol use, and a diet low in fruits or vegetables may also contribute.

A number of genetic syndromes raise the risk of adenocarcinoma in the duodenum. These include familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), which causes numerous polyps in the upper small intestine; Lynch syndrome, which impairs the body’s ability to repair DNA damage; and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, which causes distinctive polyps throughout the small bowel. People with these conditions are often monitored closely because they face a higher lifetime risk of duodenal cancer.

Ampullary s non-ampullary duodenal adenocarcinoma

Although both types occur in the duodenum, ampullary and non-ampullary adenocarcinomas behave differently. Ampullary tumors, which begin in or near the ampulla of Vater, tend to cause early symptoms such as jaundice by blocking the flow of bile. In contrast, non-ampullary tumors begin away from the ampulla, often on the opposite wall of the duodenum, and may grow significantly before causing symptoms such as bleeding or obstruction. Because of this, non-ampullary tumors are often discovered at a later stage.

Pathologists evaluate ampullary and non-ampullary tumors differently, and they are staged using different classification systems. Treatment recommendations may also differ because of their distinct patterns of growth and spread.

How is this diagnosis made?

People usually undergo imaging studies such as CT or MRI scans when experiencing unexplained abdominal pain, anemia, or symptoms of obstruction. These tests may show a mass, thickening of the duodenal wall, or signs of blockage. An upper endoscopy is often performed to directly visualize the inner surface of the duodenum. Endoscopy allows the doctor to see the tumor and remove small pieces of tissue for a biopsy.

In a biopsy, the pathologist examines the tissue under the microscope and looks for abnormal, disorganized glands; enlarged, irregular nuclei; and other features that confirm adenocarcinoma. Because a biopsy represents only a small part of the tumor, the full picture often becomes clear only after the entire tumor is removed during surgery. Examination of the resection specimen allows the pathologist to determine the tumor’s size, grade, depth of invasion, and whether cancer has entered blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, or nerves.

Immunohistochemistry may be used to help confirm the diagnosis or rule out other tumor types. This test highlights specific proteins in the cells. Certain staining patterns help distinguish adenocarcinoma from neuroendocrine tumors, lymphoma, or metastatic cancers from nearby organs such as the pancreas or stomach.

Histologic grade

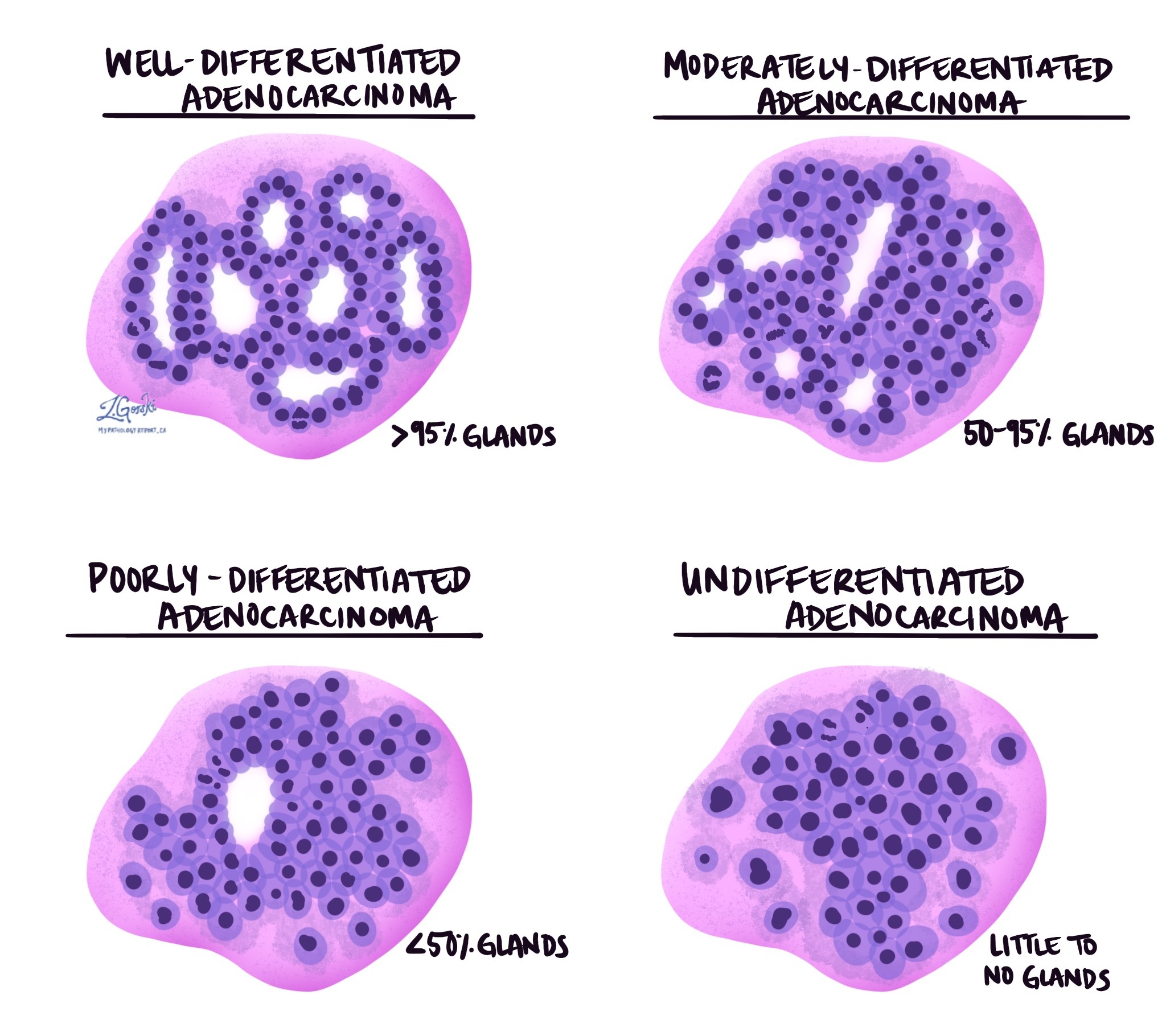

The grade describes how closely the cancer cells resemble normal duodenal gland-forming cells. Normal duodenal glands are round or tube-shaped structures that help absorb nutrients and neutralize stomach acid. In adenocarcinoma, the cancer cells may still form gland-like structures, or they may lose this ability.

Well-differentiated tumors form many glands and look somewhat similar to normal tissue. Moderately differentiated tumors form fewer glands and show more variation in shape and size. Poorly differentiated tumors form very few recognizable glands and appear much more abnormal. A small number of tumors are undifferentiated, meaning no gland formation can be seen. Higher-grade tumors tend to grow more quickly and are more likely to spread.

Tumor extension (depth of invasion)

Non-ampullary adenocarcinoma of the duodenum starts in the epithelium, the inner lining of the intestine. Beneath the epithelium is the lamina propria, a thin layer of connective tissue, followed by the submucosa, which contains blood vessels and lymphatic channels. Below that is the muscularis propria, a thick layer of muscle responsible for moving food. The outer surface of the duodenum is covered by the serosa.

As the tumor grows, it can invade progressively deeper layers of the duodenal wall. Tumors limited to the mucosa behave less aggressively. Those that invade the muscularis propria, serosa, or nearby organs have a higher risk of spreading. The depth of invasion is used to determine the pathologic T stage, which is an important part of cancer staging.

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion (PNI) means cancer cells are found around nerves within the tissue surrounding the tumor. Nerves act like cables carrying messages such as pain or temperature. Cancer cells that grow along nerves can travel deeper into nearby tissues, making the tumor harder to remove completely. This finding is associated with a higher risk of recurrence and is included in the pathology report because it affects prognosis.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means cancer cells have entered blood vessels or lymphatic vessels near the tumor. Blood vessels carry blood throughout the body, while lymphatic vessels carry lymph fluid to lymph nodes. When cancer cells enter these vessels, they can travel to lymph nodes or distant organs. This finding is important because it increases the likelihood of metastasis and helps determine the tumor’s stage.

Margins

A margin is the edge of tissue removed during surgery. After the tumor is removed, the pathologist examines the margins to ensure no cancer cells are present at the cut edge. A negative margin means the tumor was entirely removed, while a positive margin means cancer cells reach the edge of the tissue, suggesting that some tumor may remain. When possible, the pathologist will also report the distance between the tumor and the nearest margin. Margin status is important because it helps guide decisions about the need for additional treatment.

Special microscopic features

Some non-ampullary duodenal adenocarcinomas have features that provide additional information about behavior. Signet ring cell features occur when cancer cells fill with mucus, pushing the nucleus to one side. These tumors often behave more aggressively. Mucinous features describe tumors that produce large amounts of mucus; if more than half of the tumor consists of mucus-producing cells, it is called mucinous adenocarcinoma. Rarely, tumors show squamous differentiation, meaning some cancer cells resemble squamous cells, the flat cells found in the skin or esophagus. This unusual feature may also indicate more aggressive behavior.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes near the duodenum are usually removed during surgery so they can be examined for cancer. Cancer cells can travel from the tumor into lymphatic vessels and then into lymph nodes. The pathologist will report the total number of lymph nodes examined and the number that contain cancer. If cancer cells break through the outer capsule of a lymph node into surrounding tissue, this is called extranodal extension. Lymph node involvement is used to determine the pathologic N stage and is one of the most important predictors of prognosis.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

The pathologic stage describes how far the cancer has spread at the time of surgery. The stage is based on how deeply the tumor has invaded the duodenal wall (the T category), whether cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (the N category), and whether it has spread to distant organs (the M category). Early-stage tumors that have not spread to lymph nodes generally have a better outlook. More advanced tumors that invade surrounding organs or involve multiple lymph nodes may require additional treatment. Your healthcare team will combine the pathology findings with imaging results to determine the final stage and create a personalized treatment plan.

Biomarkers

Biomarker testing helps doctors understand how the tumor behaves and whether certain treatments may be effective. Two of the most important biomarkers for duodenal adenocarcinoma are mismatch repair (MMR) proteins and HER2. Testing can be done on biopsy tissue or on the tumor after surgery.

MMR testing evaluates four proteins—MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2—that help repair DNA damage. When one or more of these proteins is missing, the tumor is called mismatch repair deficient (dMMR). These tumors often show microsatellite instability (MSI), which is another indicator of impaired DNA repair. Identifying a mismatch repair deficient tumor is important because these cancers may respond well to immune checkpoint inhibitors, a type of immunotherapy that can be used for several cancer types. Testing also helps identify people with Lynch syndrome, an inherited condition that increases the risk of multiple cancers.

HER2 is another biomarker that may be tested, especially for advanced or recurrent tumors. HER2 is a protein that sits on the surface of some cancer cells. Tumors with increased HER2 activity are called HER2-positive, and several targeted therapies are available for these cancers. Although HER2 testing is most commonly used in breast and stomach cancers, it is increasingly applied to advanced gastrointestinal cancers, including duodenal adenocarcinoma.

Pathologists use immunohistochemistry to measure these proteins, and sometimes additional molecular tests such as PCR or next-generation sequencing are performed to identify genetic changes. The results help guide treatment decisions and identify potential targeted therapies.

Prognosis

The prognosis for non-ampullary adenocarcinoma of the duodenum depends on the tumor’s stage, grade, depth of invasion, lymph node involvement, and whether it shows lymphovascular or perineural invasion. Tumors detected early, before they spread to lymph nodes or distant organs, have a more favorable outlook. Non-ampullary tumors often present later than ampullary tumors, which can affect prognosis. Even so, many people benefit from surgery and modern treatments, especially when the tumor is localized. Your healthcare team will use the pathology findings and imaging results to estimate prognosis and recommend appropriate treatment.

After the diagnosis

After the pathology report is completed, your doctor will review the findings with you and explain the next steps. Additional imaging studies may be used to determine whether the cancer has spread. Many people are referred to a medical oncologist to discuss treatment options such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or participation in clinical trials. If surgery was the first step, follow-up care may involve regular imaging and blood tests to monitor for recurrence. Your healthcare team will create a personalized plan based on the tumor’s features and your overall health.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

Where exactly in the duodenum did my tumor start?

- Did the tumor spread to lymph nodes or nearby organs?

-

What was the tumor’s grade?

-

Were lymphovascular or perineural invasion seen in the pathology report?

-

Were the surgical margins clear?

-

Do I need additional imaging or treatment?

-

Are biomarker tests such as MMR or HER2 relevant for my tumor?

-

What are my treatment options moving forward?