by Catherine Forse MD FRCPC and Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

July 26, 2025

Intramucosal adenocarcinoma is an early form of esophageal cancer that starts in the mucosa, the innermost layer of the esophageal wall. The term intramucosal means that the tumor cells are still confined to this thin inner layer and have not spread deeper into the esophagus. Because the tumor is detected at an early stage, treatment options are often less invasive and may include endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

What are the symptoms of intramucosal adenocarcinoma in the esophagus?

Some people may have no symptoms, especially if the tumor is discovered early. However, others may experience symptoms similar to acid reflux or more advanced esophageal conditions, such as:

-

Difficulty swallowing (especially solid foods).

-

Chest discomfort or pain.

-

Worsening heartburn or acid reflux.

-

Unexplained weight loss.

What causes intramucosal adenocarcinoma of the esophagus?

This type of cancer usually develops from a precancerous condition called Barrett esophagus. Barrett’s esophagus occurs when the normal squamous cells that line the esophagus are replaced by glandular cells, which are more resistant to damage from stomach acid. This change is called intestinal metaplasia.

Barrett’s esophagus is caused by long-term acid reflux (also known as gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD), where stomach acid repeatedly flows back into the esophagus and damages the lining. Over time, the cells in Barrett esophagus can become abnormal, a condition called dysplasia, which may then progress to intramucosal adenocarcinoma.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis is made after a biopsy or tissue sample is taken during an upper endoscopy. A pathologist examines the tissue under a microscope and looks for evidence of adenocarcinoma that is limited to the mucosa. Because intramucosal adenocarcinoma is an early form of cancer, it is often discovered during routine surveillance in patients with known Barrett esophagus.

What to look for in your pathology report

Histologic grade

Pathologists assign a grade to intramucosal adenocarcinoma based on how closely the cancer cells resemble normal gland-forming cells. The grade gives important information about how aggressive the tumor may be:

-

Grade 1 (well differentiated): More than 95% of the tumor forms gland-like structures.

-

Grade 2 (moderately differentiated): 50–95% of the tumor forms glands.

-

Grade 3 (poorly differentiated): Less than 50% of the tumor forms glands.

Poorly differentiated tumors are generally more aggressive and more likely to spread than well differentiated ones.

Depth of invasion and pathologic tumor stage (pT)

The mucosa is made up of three layers: the epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae. By definition, intramucosal adenocarcinoma means the tumor has grown into one or more of these layers but has not invaded the submucosa (the layer beneath the mucosa). For this reason, all cases are assigned a pathologic tumor stage of pT1a.

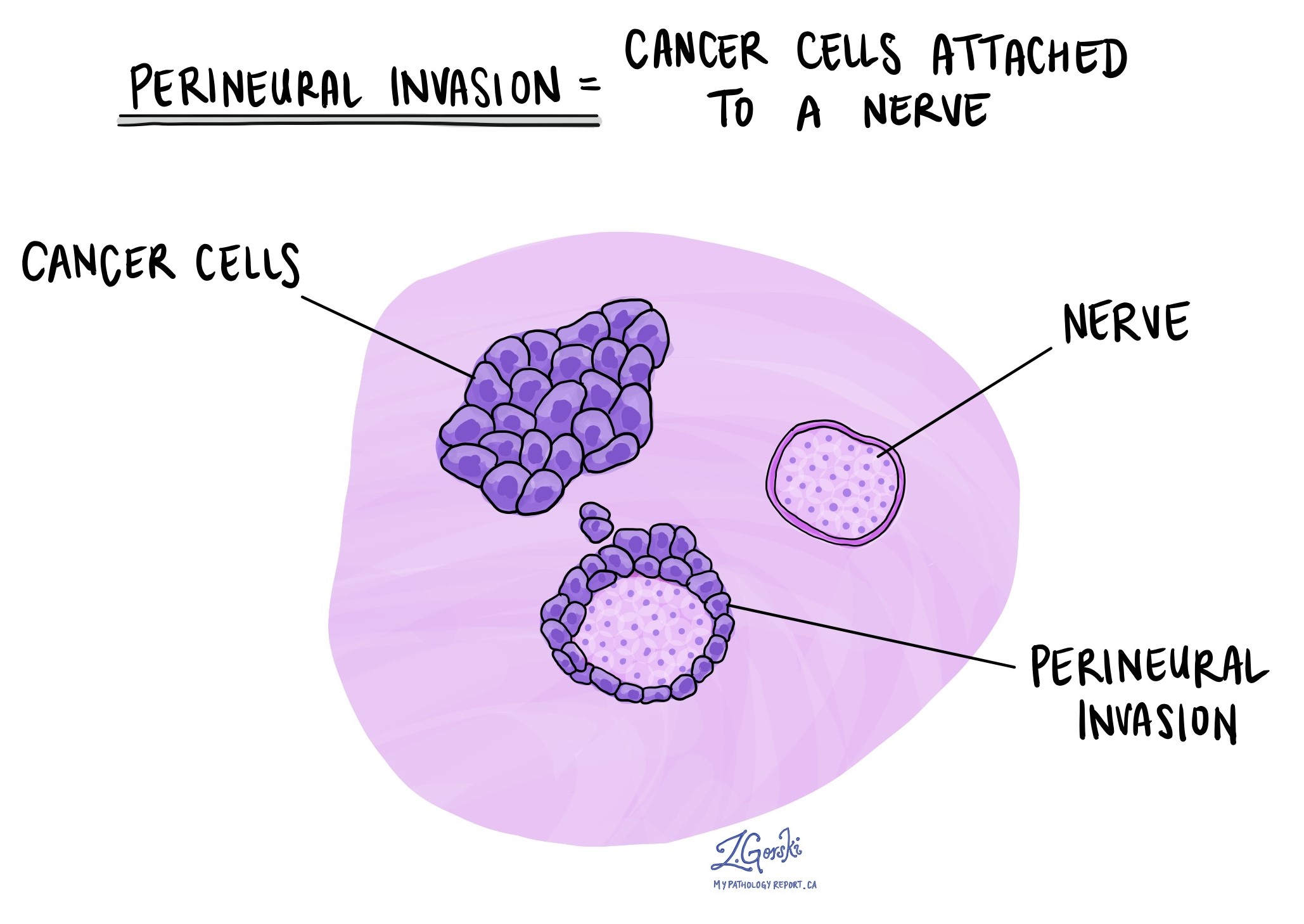

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion (PNI) means that cancer cells are seen growing around or into nerves. While this feature is more commonly seen in more advanced tumors, if it is found in an intramucosal adenocarcinoma, it may suggest a higher risk of recurrence. The pathology report will describe this finding as either present (positive) or absent (negative).

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) refers to cancer cells invading small blood vessels or lymphatic channels near the tumor. This is an important finding because it may allow cancer cells to spread to other parts of the body, such as lymph nodes or distant organs. LVI is reported as present or absent in the pathology report.

Treatment effect

If you received chemotherapy, radiation, or both before the tumor was removed, your pathologist will evaluate how much of the tumor was destroyed by the treatment. This is called tumor regression.

The most common scoring system uses the following categories:

-

Score 0 – No viable cancer cells (complete response).

-

Score 1 – Only single cells or rare groups of cancer cells remain.

-

Score 2 – Cancer cells remain, but there are signs the tumor has responded.

-

Score 3 – Extensive cancer remains, with little or no evidence of regression.

This information helps doctors understand how well the cancer responded to treatment and whether additional therapy is needed.

Margins

In pathology, the margin refers to the edge or border of the tissue that was removed during surgery or an endoscopic procedure. After the tissue is removed, a pathologist examines the margins under a microscope to determine whether any cancer cells are present at the very edge. This helps your doctor understand whether the tumor was completely removed or if some cancer cells may have been left behind.

Why are margins important?

If cancer cells are found at a margin, the report will describe it as a positive margin. This means that some cancer may still be in your body at or near the site of removal. A negative margin means that there are no cancer cells at the edge of the tissue, suggesting that the tumor was completely removed.

In some cases, the report may also measure the distance between the tumor and the nearest margin. Even if the margins are negative, a close margin (usually defined as less than 1 or 2 millimeters) may increase the risk that cancer could come back in the future. This information can help your doctors decide whether additional treatment or close follow-up is needed.

Types of margins in endoscopic resections

In endoscopic resections, such as endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), only a small, localized area of the inner lining of the esophagus is removed. The pathology report may describe several different types of margins, depending on the shape and orientation of the tissue removed:

-

Lateral margins (also called mucosal margins): These are the edges around the sides of the tissue sample. They represent the cut surfaces along the inner lining of the esophagus (mucosa). Pathologists look here to see if the tumor is growing up to the side edges of the specimen.

-

Deep margin (also called vertical margin): This is the bottom edge of the sample and represents the tissue deeper in the esophagus, such as the muscularis mucosae or possibly the top of the submucosa. The deep margin is especially important in intramucosal adenocarcinoma because the tumor should not go beyond this point.

Some pathology reports may also refer to:

-

Radial margin: In full-thickness surgical specimens, the radial margin refers to the tissue that surrounds the esophagus on the outside. This margin is not typically relevant in endoscopic resections.

Biomarker testing

HER2

HER2 is a protein that promotes cell growth. Some esophageal adenocarcinomas produce too much HER2, which may cause the tumor to grow faster. Testing for HER2 helps doctors determine whether HER2-targeted therapies, such as trastuzumab, may be effective.

HER2 is usually tested using a method called immunohistochemistry (IHC):

-

0 or 1+ (Negative): HER2 is not overproduced.

-

2+ (Equivocal): Unclear result; a second test called FISH is performed.

-

3+ (Positive): HER2 is overproduced; targeted therapy may be helpful.

Mismatch repair (MMR) proteins

MMR proteins (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6) help fix errors in DNA. If one or more of these proteins are missing, the DNA repair system is not working properly, which may increase the risk of cancer and affect how the tumor responds to immunotherapy.

Testing is done using immunohistochemistry:

-

Normal (retained expression): All four proteins are present.

-

Abnormal (loss of expression): One or more proteins are missing.

Patients with abnormal MMR results may be tested further for Lynch syndrome, a genetic condition that increases the risk of several types of cancer.

PD-L1

PD-L1 is a protein that helps cancer cells hide from the immune system. Tumors that express PD-L1 may respond better to immune checkpoint inhibitors, a type of cancer treatment.

PD-L1 is tested using immunohistochemistry, and results are reported using a combined positive score (CPS). A CPS of 1 or higher is considered positive, meaning you may benefit from immunotherapy.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What is the grade of my intramucosal adenocarcinoma?

-

Were any cancer cells found at the margins?

-

Was there any evidence of lymphovascular or perineural invasion?

-

Do I need additional treatment such as surgery or surveillance?

-

Were biomarker tests like HER2, MMR, or PD-L1 performed on my tumor?

-

How does this diagnosis affect my long-term outlook and follow-up plan?