by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD

February 5, 2024

Squamous cell carcinoma is a type of cancer that starts from the squamous cells that normally line the inside surface of the esophagus, the tube that carries food from the mouth to the stomach. These cells are flat and help protect the esophagus from injury. In squamous cell carcinoma, the squamous cells grow in an abnormal and uncontrolled way, forming a malignant (cancerous) tumor.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of esophageal cancer worldwide. It typically occurs in the middle or lower parts of the esophagus and is often diagnosed at an advanced stage. This cancer can grow into surrounding tissues and spread (metastasize) to lymph nodes and other parts of the body.

What are the symptoms of squamous cell carcinoma?

Many people do not experience symptoms until the tumor is more advanced. When symptoms do occur, they may include:

-

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia).

-

Pain when swallowing.

-

Chest or upper back pain.

-

Hoarseness or voice changes.

-

Unexplained weight loss.

Tumors in the upper esophagus may affect nerves that control the voice, leading to hoarseness. Symptoms like persistent difficulty swallowing or unexplained weight loss should prompt further testing.

What causes squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus?

Squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus of cancer is linked to long-term irritation or injury to the esophageal lining.

Risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma include:

-

Smoking tobacco.

-

Heavy alcohol use.

-

Drinking very hot liquids over long periods.

-

Poor nutrition or low intake of fruits and vegetables.

-

Certain infections (e.g., human papillomavirus or HPV).

-

Previous radiation therapy to the chest or neck.

In some regions of the world, such as parts of Asia and Africa, squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is much more common due to dietary and environmental factors.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis is usually made during an upper endoscopy, a procedure where a thin tube with a camera (an endoscope) is passed down the throat to look at the inside of the esophagus. If an abnormal area is seen, a small sample of tissue called a biopsy is taken and sent to a pathologist.

Your pathology report

Your pathology report is written by a pathologist after examining a sample of tissue from your esophagus. If the tumor was removed during surgery, your report will include information about the tumor’s size, depth of invasion, lymph node involvement, and margins. If only a biopsy was performed, the report will focus on the presence of cancer cells and any special tests used to confirm the diagnosis. Your report will also describe the tumor grade, which provides information about how abnormal the cancer cells look and how aggressive the tumor might be. This information helps your healthcare team decide on the best treatment options for you.

What does squamous cell carcinoma look like under the microscope?

When examined under the microscope, squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is made up of abnormal squamous cells that grow downward into the wall of the esophagus. These cancer cells often form groups called nests or sheets and can appear very different from the healthy squamous cells normally found on the surface of the esophagus.

Features such as keratin pearls (round clusters of keratin) and intercellular bridges (connections between cancer cells) help confirm that the tumor is a squamous cell carcinoma. In more aggressive tumors, these features may be absent, and the cells may appear more disorganized.

Other tests performed to confirm the diagnosis

Pathologists may perform additional tests on the tissue sample to confirm the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma and to help rule out other types of cancer.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunohistochemistry is a special test that uses antibodies to look for specific proteins inside cells. These proteins can help identify the type of cancer. For squamous cell carcinoma, IHC is especially useful in poorly differentiated tumors, where the cancer cells look very abnormal and the diagnosis may not be obvious by appearance alone.

The most common proteins tested by IHC for squamous cell carcinoma include:

-

p40 – This is the most specific marker for squamous cell carcinoma and is usually strongly positive in tumor cells.

-

p63 – Another marker of squamous cells, but less specific than p40. It is often positive in squamous cell carcinoma.

-

CK5/6 (cytokeratin 5/6) – These proteins are found in squamous cells and are typically positive in squamous cell carcinoma.

Tumors that test positive for p40, p63, and CK5/6 and negative for markers of glandular differentiation (such as CK7 or CDX2) are consistent with squamous cell carcinoma.

If a tumor has unusual features, your pathologist may also test for:

-

Neuroendocrine markers (such as synaptophysin or chromogranin), to rule out neuroendocrine carcinoma.

-

Adenocarcinoma markers (such as CK7 or CDX2), to rule out gland-forming cancers.

These additional tests help ensure that the diagnosis is accurate, especially when the tumor is poorly differentiated or when the pathologist is considering different types of cancer.

No molecular tests are currently required for the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, but research is ongoing to better understand the genetic changes that may guide future treatments.

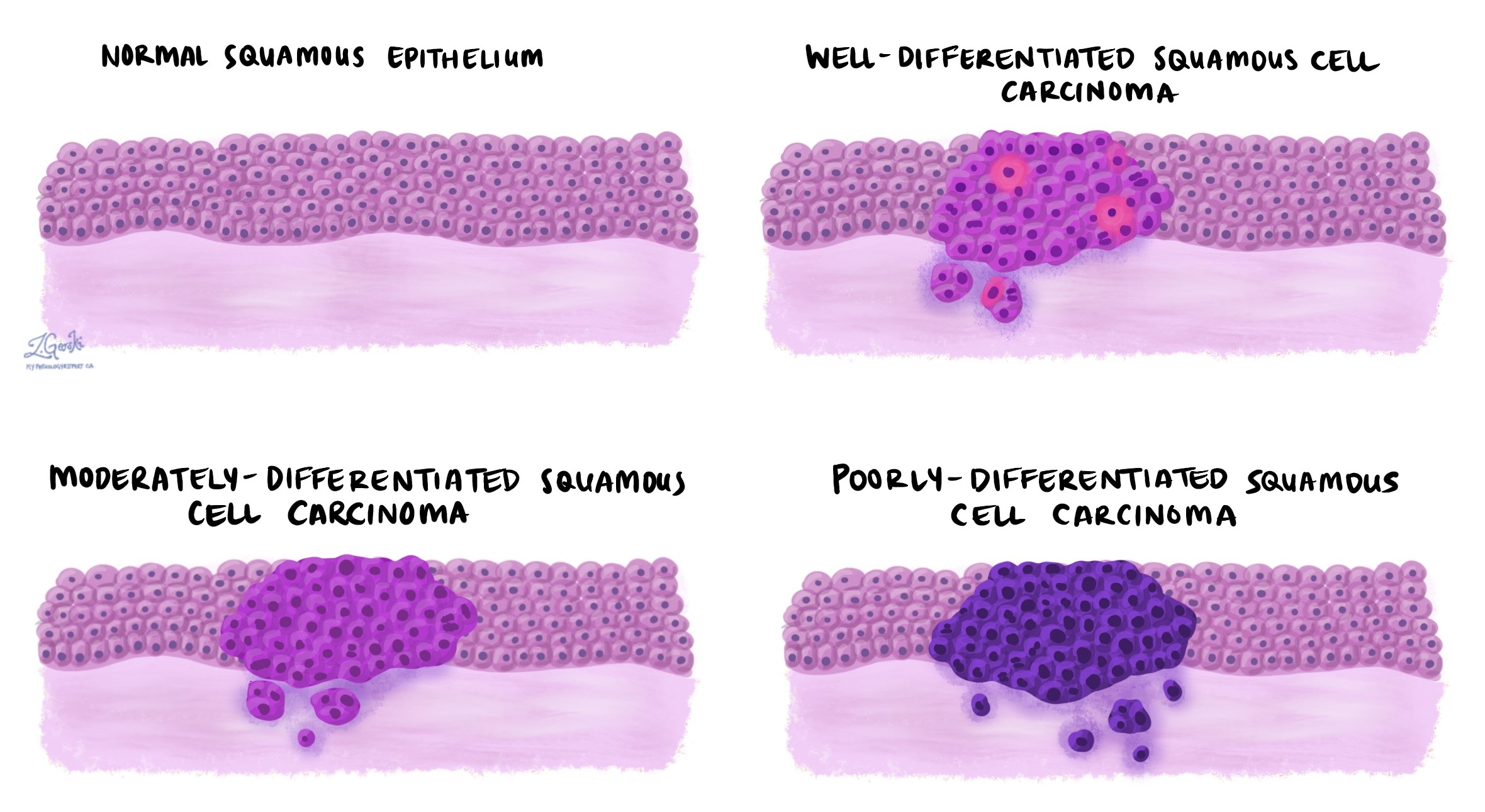

What does tumor grade mean?

The grade describes how abnormal the cancer cells look under the microscope and how much they resemble normal squamous cells found in the epithelium.

There are three grades:

Grade 1 – Well differentiated: The cancer cells look somewhat like normal squamous cells and may produce keratin. These tumors tend to grow slowly.

Grade 2 – Moderately differentiated: The cells are more abnormal and show less organization. They may grow more quickly than well-differentiated tumors.

Grade 3 – Poorly differentiated: The cells look very different from normal and may grow in disorganized sheets or nests. These tumors are more aggressive and more likely to spread.

Subtypes of squamous cell carcinoma

A subtype is a specific form of a cancer that shares the main features of the overall disease but also has unique characteristics. In squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, subtypes are defined based on the way the cancer looks under the microscope. Identifying a subtype can help pathologists provide a more detailed diagnosis and may give your doctors more information about how the cancer might behave.

The main subtypes of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus include:

Verrucous squamous cell carcinoma

Verrucous squamous cell carcinoma is a rare and slow-growing subtype. It often develops in the lower third of the esophagus, especially in people with long-term irritation or inflammation such as chronic esophagitis. Under the microscope, this subtype appears very well differentiated, meaning the cancer cells look more like normal squamous cells. It tends to form thick, warty (verrucous) growths and shows little cellular abnormality. The tumor grows slowly and is less likely to spread to other parts of the body compared to other types of squamous cell carcinoma. Because of this, it generally has a better prognosis.

Spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma

This subtype, also called sarcomatoid carcinoma, contains two types of cancer cells: squamous cells and spindle-shaped cells. The squamous component may be seen on the surface of the tumor, while the deeper part contains the spindle-shaped cells, which look very different under the microscope and may resemble other types of cancer. These tumors often grow as polyp-like masses that stick into the space inside the esophagus (the lumen). Although the spindle cells can look aggressive, these tumors may be less invasive and may respond well to treatment, especially if diagnosed early.

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma is a rare but aggressive subtype. The cancer cells are small and dark, resembling basal cells found in the lower layer of the normal esophageal lining. These tumors often grow in solid sheets or nests and may have central areas of cell death (called necrosis). They can sometimes look similar to other types of cancer, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma or high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, so additional testing may be required to make the correct diagnosis. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma often grows quickly and can spread early, so it is usually treated more aggressively.

Each subtype is still considered a type of squamous cell carcinoma, and your pathologist will include this information in your pathology report if one of these special forms is seen. If no specific subtype is mentioned, the tumor is typically classified as conventional squamous cell carcinoma.

What does invasion mean in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus?

Invasion describes how deeply the cancer has grown into the layers of the esophagus or into nearby structures outside the esophagus. Squamous cell carcinoma starts from squamous cells that form the inner lining of the esophagus, called the mucosa. As the tumor grows, it can extend through deeper layers of the esophagus and may spread into surrounding tissues and organs.

The esophagus is made up of several layers of tissue, listed here from the innermost layer to the outermost:

-

Mucosa: The inner lining where squamous cell carcinoma begins. It includes thin layers called the lamina propria and muscularis mucosae.

-

Submucosa: A layer of connective tissue just beneath the mucosa.

-

Muscularis propria: A thick layer of muscle that contracts to move food toward the stomach.

-

Adventitia: The outer layer of connective tissue that surrounds and supports the esophagus. Unlike other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, the esophagus does not have a serosal covering.

As the tumor grows, it may invade through these layers. In more advanced cases, the cancer can spread beyond the esophagus into nearby structures such as the windpipe (trachea), aorta, or tissue around the heart (pericardium).

Pathologists determine how far the tumor has invaded by examining the tissue under a microscope. The deepest point of invasion is used to assign the pathologic tumor stage (pT), which is part of the TNM staging system. The pT stage helps your doctors assess how advanced the cancer is and guides treatment decisions.

Pathologic tumor stage (pT) for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus

pT1: The cancer is in an early stage and has grown only into the inner layers of the esophagus. These include the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa, which lie just beneath the surface.

pT1a: The cancer is limited to the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae, the shallowest layers within the mucosa.

pT1b: The cancer has grown into the submucosa, a deeper supportive tissue beneath the mucosa.

pT2: The cancer has reached the muscularis propria, the thick muscle layer that helps move food through the esophagus.

pT3: The cancer has grown through the muscle layer and into the adventitia, the outer connective tissue that surrounds the esophagus.

pT4: The cancer has spread beyond the esophagus into nearby organs or structures.

pT4a: The tumor has invaded nearby but potentially resectable structures, such as the pleura (lining of the lungs), pericardium (lining around the heart), azygos vein, diaphragm, or peritoneum (lining of the abdominal cavity). These tumors may still be treated with surgery.

pT4b: The tumor has invaded critical structures such as the aorta, vertebral body (spinal bones), or airways. These tumors are usually considered more advanced and are often not removable with surgery.

PD-L1 testing

PD-L1 is a protein that some cancer cells use to hide from the immune system. By producing PD-L1, these cells avoid being attacked by immune cells. Immunotherapy drugs, called immune checkpoint inhibitors, work by blocking this signal so the immune system can find and destroy the cancer.

To see if immunotherapy might work, pathologists test for PD-L1 using a score called the Combined Positive Score (CPS). CPS compares the number of PD-L1-producing cells (both cancer cells and nearby immune cells) to the total number of tumor cells.

What do the results mean?

-

Positive (CPS ≥ 1) – PD-L1 is present. Immunotherapy may be an effective treatment option.

-

Negative (CPS < 1) – Very little or no PD-L1 is present. Immunotherapy is less likely to work, although it may still be considered in some situations.

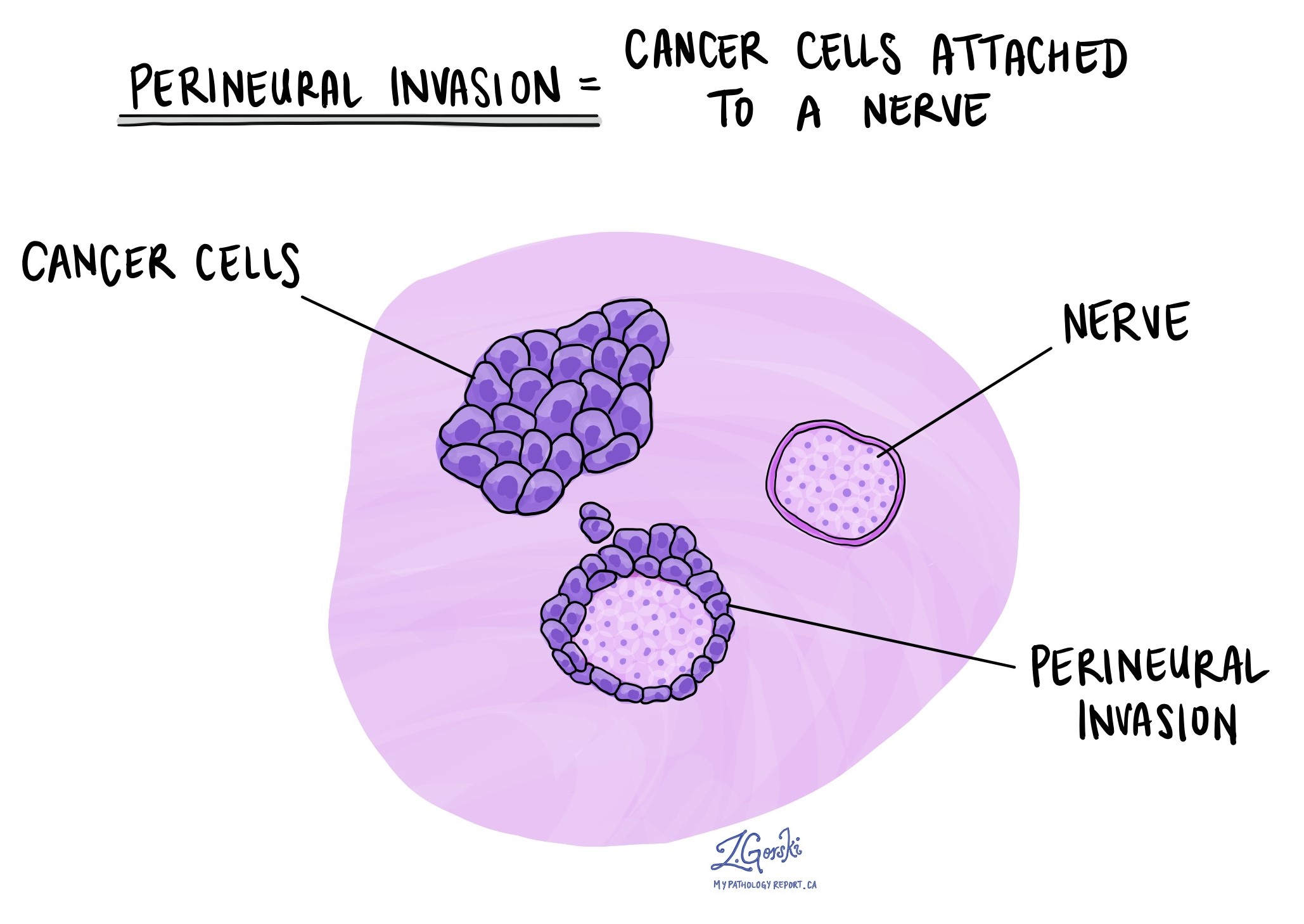

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion (PNI) means that cancer cells are seen growing along or around a nerve in the tissue surrounding the esophagus. Nerves are structures that carry signals between your brain and the rest of your body, including the muscles that help move food through the esophagus.

Pathologists look for perineural invasion by examining the tissue under a microscope. They may see cancer cells wrapping around the outside of a nerve or invading into the nerve itself. The presence of PNI suggests that the cancer is spreading into nearby structures, which may make it more likely to come back after treatment or spread to other parts of the body.

If perineural invasion is found, your pathology report will describe it as positive or present. If no cancer cells are seen near nerves, the report will say negative or absent.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means that cancer cells have entered small blood vessels or lymphatic channels near the tumor. These vessels provide a way for cancer cells to spread to other parts of the body, such as the lymph nodes or distant organs.

Blood vessels carry blood, oxygen, and nutrients to and from tissues. Lymphatic vessels are part of the immune system and help drain waste and carry immune cells. When cancer cells are seen inside these vessels, it is a sign that the tumor has the potential to spread.

Pathologists examine the tissue under the microscope and look for groups of cancer cells inside the walls of these vessels. Sometimes, special tests called immunohistochemistry are used to help confirm the presence of tumor cells inside the vessels.

If lymphovascular invasion is seen, your report will describe it as present or positive. If no cancer is found in the vessels, the report will say absent or negative. The presence of LVI is considered a high-risk feature and may lead your doctor to recommend additional treatment, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, after surgery.

Margins

In cancer surgery, the margin refers to the edge or border of the tissue removed along with the tumor. After surgery, a pathologist examines these margins under a microscope to determine whether any cancer cells are present at the edge.

The goal of surgery is to remove the tumor completely, with a rim of normal tissue around it. If cancer cells are seen at the edge of the tissue, it may mean that some of the tumor was left behind. Your pathology report will describe the margin status as:

-

Negative (clear or uninvolved): No cancer cells are seen at the edge. This suggests that the tumor was completely removed.

-

Positive (involved): Cancer cells are seen at the edge. This may indicate that cancer remains in the body and additional treatment may be needed.

Different types of margins may be described in your report depending on the surgery and the tumor’s location:

-

Mucosal (lateral) margin: The edge of the inner lining of the esophagus next to the tumor.

-

Deep margin: The tissue deeper in the wall of the esophagus, underneath the tumor.

-

Proximal margin: The upper edge of the removed tissue, closer to the mouth.

-

Distal margin: The lower edge, closer to the stomach.

-

Radial margin: The outer surface of the esophagus, which is important when the tumor has grown outward through the wall.

Your report will list whether each margin is positive or negative. This information is important for determining whether more treatment is needed.

Lymph nodes and pathologic nodal stage (pN)

Lymph nodes are small immune organs that help filter harmful substances and play a role in fighting infections. They are connected to the rest of the body by a network of lymphatic vessels, which can also transport cancer cells. When cancer spreads from the esophagus, the lymph nodes are often the first place it goes.

During surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, nearby lymph nodes are removed and sent to the lab for examination. The pathologist looks at each lymph node under the microscope to see if it contains cancer cells. Your report will describe the lymph nodes as either:

-

Positive: Cancer cells are found in the lymph node.

-

Negative: No cancer cells are found in the lymph node.

The number of positive lymph nodes helps determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN), which is part of the overall cancer staging system. This stage helps your doctors understand how far the cancer has spread and what treatments are most appropriate.

Pathologic nodal staging for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus:

-

pN0: No cancer found in any lymph nodes.

-

pN1: Cancer found in 1 or 2 lymph nodes.

-

pN2: Cancer found in 3 to 6 lymph nodes.

-

pN3: Cancer found in 7 or more lymph nodes.

-

pNX: No lymph nodes were sent or evaluated.

Lymph node involvement is an important prognostic factor. If cancer is found in the lymph nodes, your doctor may recommend additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy, to reduce the risk of the cancer returning or spreading further.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What part of my esophagus was affected by the tumor?

-

What was the tumor grade, and what does it mean for my treatment?

-

How deeply did the tumor grow into the esophagus?

-

Were any lymph nodes involved?

-

Were the surgical margins clear of cancer?

-

Did the tumor show lymphovascular or perineural invasion?

-

Did I have a good response to chemotherapy or radiation?

-

What are my next steps in treatment?

-

Should I consider genetic or immunotherapy testing?