by Katherina Baranova MD and Matt Cecchini MD FRCPC

June 19, 2025

An atypical carcinoid tumour is a type of lung cancer. It develops from special cells in the lungs called neuroendocrine cells. These cells normally produce hormones that help regulate breathing and airflow in the lungs.

Atypical carcinoid tumours usually grow in the central area of the lung near the airways. When the tumour grows large enough, it can block the airways. This blockage can make it hard to breathe and may cause parts of the lung to collapse. Sometimes, the tumour also grows into the airway itself, causing symptoms like coughing up blood.

Although atypical carcinoid tumours grow slowly compared to many other types of lung cancer, they have a higher chance of spreading to nearby lymph nodes or other organs, such as the liver, compared to typical carcinoid tumours.

Is an atypical carcinoid tumour a type of cancer?

Yes, an atypical carcinoid tumour is a type of cancer. It is part of a group of cancers known as neuroendocrine tumours. While it grows more slowly than many other types of lung cancer, it can still spread to other areas of the body if not treated early.

Can an atypical carcinoid tumour spread to other parts of the body?

Yes, atypical carcinoid tumours can metastasize (spread) beyond the lung. They most commonly spread to nearby lymph nodes. Occasionally, they also spread to distant organs, such as the liver and bones. However, this happens less often compared to more aggressive types of lung cancer, such as small cell lung cancer.

What causes an atypical carcinoid tumour?

Doctors don’t know exactly why atypical carcinoid tumours form. Unlike many other types of lung cancer, these tumours are usually not strongly linked to smoking or other environmental factors. However, some genetic conditions can increase the risk of developing these tumours.

What are the symptoms of an atypical carcinoid tumour?

Symptoms depend on the size of the tumour and its location within the lungs. Small tumours may not cause noticeable symptoms, but larger tumours or those near airways typically cause symptoms like:

-

Cough that won’t go away

-

Shortness of breath

-

Wheezing or noisy breathing

-

Coughing up blood

-

Chest pain or discomfort

Sometimes, atypical carcinoid tumours produce hormones like serotonin. High levels of serotonin can lead to a condition called carcinoid syndrome. Symptoms of carcinoid syndrome include flushing (skin turning red), diarrhea, and wheezing. However, carcinoid syndrome usually only happens if the tumour has spread to the liver.

How is an atypical carcinoid tumour diagnosed?

Your doctor may suspect an atypical carcinoid tumour based on symptoms or imaging tests, like an X-ray or CT scan of your chest. To confirm the diagnosis, your doctor will usually perform a biopsy or fine needle aspiration (FNA). In these procedures, a small sample of tissue or cells is taken from the tumour in your lung. This sample is then examined under a microscope by a pathologist. Sometimes, your doctor might recommend removing the entire tumour through surgery to make a definite diagnosis and for treatment.

What does an atypical carcinoid tumour look like under the microscope?

Under a microscope, atypical carcinoid tumours contain cells that look very similar to each other. The cells have a distinctive pattern in their nucleus described by pathologists as “salt and pepper”. This pattern comes from tiny dark dots scattered throughout the nucleus.

Your pathologist will also look at how many tumour cells are dividing, a process called mitosis. Tumours with 2 to 10 dividing cells per 2 square millimeters are called atypical carcinoid tumours. Tumours with fewer dividing cells (less than 2) and no areas of cell death (necrosis) are called typical carcinoid tumours. This distinction is important because atypical carcinoid tumours have a higher risk of recurrence after surgery and metastasis to other body parts.

What other tests may be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

Your pathologist may perform additional tests, such as immunohistochemistry, to confirm the diagnosis. This test uses special stains that show specific proteins within tumour cells. Atypical carcinoid tumour cells usually test positive for proteins such as chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD56, and TTF-1. These results help confirm the tumor’s neuroendocrine origin and distinguish it from other types of lung cancer.

Margins

A margin is the edge of tissue that a surgeon removes when taking out a tumour. Margins are important because they indicate whether the tumour has been completely removed. Your pathologist examines these margins very carefully under a microscope.

-

A negative margin means no cancer cells were found at the edge, suggesting the tumour was fully removed.

-

A positive margin means cancer cells were seen at the edge, indicating that some tumour may have been left behind. A positive margin increases the risk of the tumour growing back.

If the margins are positive, your doctor may recommend additional treatments, such as surgery or radiation, to remove any remaining tumour cells.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small structures in your body that help fight infections. Cancer cells from the lung can spread to lymph nodes through tiny channels called lymphatic vessels. When lymph nodes contain cancer cells, doctors describe them as positive. If no cancer cells are found, the lymph nodes are called negative.

During surgery, your doctor may remove lymph nodes from different areas around your lungs and chest. These areas are referred to as lymph node stations. There are 14 different lymph node stations in the chest.

Your pathology report will mention:

-

The number of lymph nodes removed.

-

The number of lymph nodes with cancer cells and the location of the lymph nodes involved.

Finding tumour cells in lymph nodes is important because it affects the nodal stage and may lead your doctor to recommend additional treatment, such as chemotherapy.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

Doctors use a system called the TNM system to determine the stage of an atypical carcinoid tumour. This system looks at three main factors:

-

T (Tumour) – Size and location of the tumour.

-

N (Nodes) – Presence or absence of cancer cells in lymph nodes.

-

M (Metastasis) – Whether cancer has spread to distant parts of the body.

The final pathologic stage (pTNM) helps doctors understand how advanced the tumour is and plan your treatment.

Tumour stage (pT)

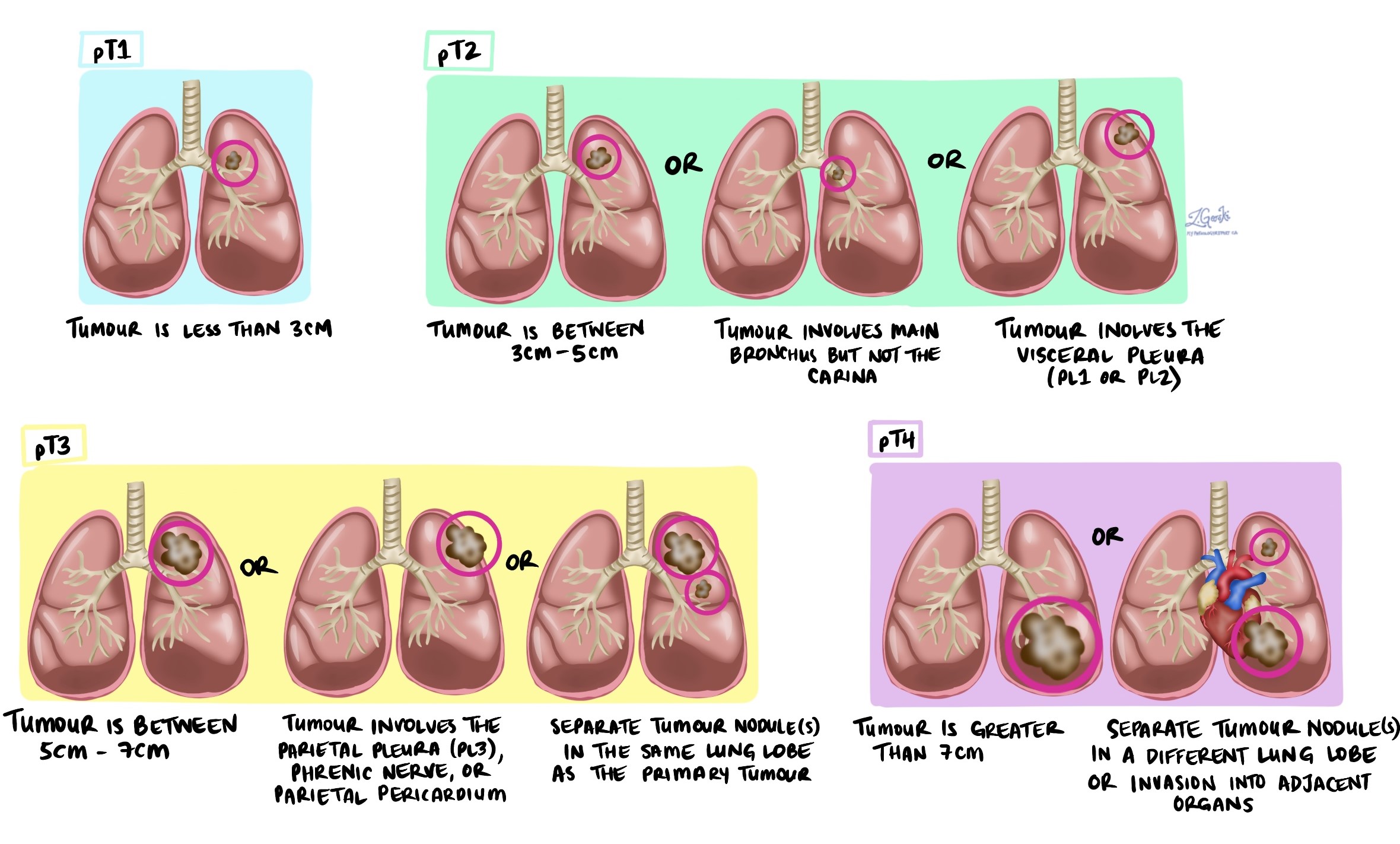

The tumour stage for atypical carcinoid tumours is determined by examining the size of the tumour and whether it has spread to nearby tissues or structures in the chest. Your pathologist will assign a stage from 1 to 4 based on the following criteria:

-

T1 – The tumour is 3 cm or smaller and is completely inside the lung without involving the main airways or the outer lining of the lung (visceral pleura).

-

T2 – The tumour is larger than 3 cm but not larger than 5 cm, or it has grown into a large airway (main bronchus), or it has spread to the outer lining of the lung (visceral pleura).

-

T3 – The tumour is larger than 5 cm but not larger than 7 cm, or it has spread directly into nearby structures such as the chest wall, the diaphragm (the muscle below your lungs), the lining around the heart (pericardium), or it is close to where the windpipe (trachea) divides into the left and right lungs.

-

T4 – The tumour is larger than 7 cm or has spread extensively into nearby structures such as the heart, the windpipe (trachea), the esophagus (food pipe), the backbone (spine), or another lobe of the lung.

The tumour stage is important because higher stages typically indicate a tumour that is larger or has spread more extensively, which can influence your treatment plan and prognosis.

Nodal stage (N)

The nodal stage depends on whether tumour cells are found in lymph nodes and which lymph node stations are involved:

-

NX – No lymph nodes were examined.

-

N0 – No tumour cells found in any lymph nodes examined.

-

N1 – Tumour cells found in lymph nodes inside the lung or around the airways leading into the lung (stations 10 to 14).

-

N2 – Tumour cells found in lymph nodes in the middle of the chest (stations 7 to 9).

-

N3 – Tumour cells found in lymph nodes near the neck or on the opposite side of the body from the tumour (stations 1 to 6).

Treatment options for atypical carcinoid tumours

Surgery is usually the first choice of treatment for atypical carcinoid tumours. The type of surgery depends on the tumour’s size and location. Surgery may involve removing:

-

A small part of the lung (wedge resection).

-

One lobe of the lung (lobectomy).

-

The entire lung (pneumonectomy).

Depending on the tumor’s stage, your doctor might recommend additional treatments after surgery. These may include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or targeted therapies.

Questions to ask your doctor

- What stage is my atypical carcinoid tumour?

- Has my tumour spread to lymph nodes or other parts of my body?

- Will I require additional tests or treatments?

- How frequently will I need follow-up appointments?

- What signs or symptoms should prompt me to seek immediate medical attention?