by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD FRCPC

April 19, 2025

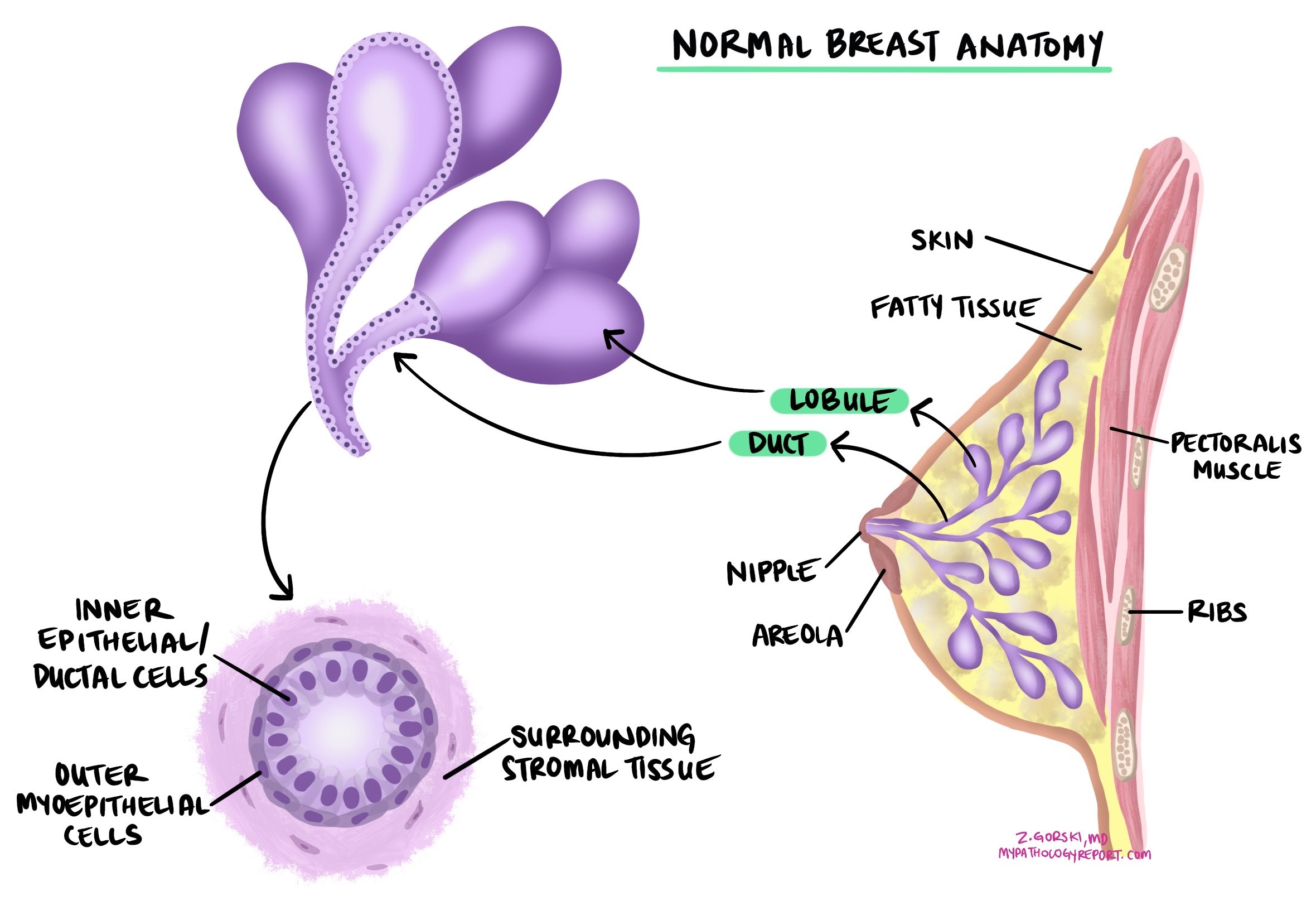

Invasive ductal carcinoma is the most common type of breast cancer. It originates from epithelial cells lining the ducts of the breast and spreads into the surrounding breast tissue. If not treated, invasive ductal carcinoma can spread to other body parts, such as the lymph nodes, bones, and lungs. Another name for this type of cancer is invasive breast carcinoma.

What are the symptoms of invasive ductal carcinoma?

Symptoms of invasive ductal carcinoma can vary, but common symptoms include:

- Lump or mass: The most common symptom is the development of a new lump or mass in the breast. These lumps are often hard and irregular in shape, but they can also be soft or round.

- Changes in breast shape or size: Any noticeable change in the size, shape, or appearance of the breast.

- Skin changes: Dimpling, puckering, or redness of the skin on the breast.

- Nipple changes: Inversion of the nipple, discharge (especially if it is bloody), or changes in the nipple’s appearance.

- Pain: Although breast pain is more commonly associated with benign conditions, some women with invasive ductal carcinoma may experience persistent pain in a specific area of the breast.

- Swelling: Swelling of part or all of the breast, even if no lump is felt.

- Enlarged lymph nodes: Swelling or lumps in the lymph nodes under the arm or around the collarbone.

What causes invasive ductal carcinoma?

The exact cause of invasive ductal carcinoma is not known, but several factors can increase the risk of developing this type of breast cancer:

- Genetic factors: Mutations in specific genes, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, substantially increase the risk of developing breast cancer. A family history of breast cancer also suggests a genetic predisposition.

- Hormonal factors: Prolonged exposure to estrogen and progesterone, such as starting menstruation at an early age, late menopause, having no children or having the first child after age 30, and hormone replacement therapy, can increase the risk.

- Age: The risk of developing invasive ductal carcinoma increases with age, particularly after age 50.

- Personal history of breast conditions: Having a history of breast cancer or certain non-cancerous breast conditions such as usual ductal hyperplasia (UDH) or atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) can increase the risk.

- Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): DCIS is a non-invasive form of breast cancer confined to the ducts. While it is not invasive, it can increase the risk of developing invasive ductal carcinoma if not treated.

- Radiation exposure: Previous radiation therapy to the chest, especially during childhood or young adulthood, can increase the risk.

- Lifestyle factors: Alcohol consumption, obesity, and lack of physical activity are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer.

- Environmental factors: Exposure to certain chemicals and environmental pollutants may contribute to the risk, although the relationship between these factors and the risk is less well understood.

What genetic changes are associated with invasive ductal carcinoma?

Specific genetic changes can increase the risk of developing invasive ductal carcinoma. Mutations in genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 are among the most well-known risk factors for breast cancer. These genes usually help repair DNA damage, but mutations can prevent them from working correctly, leading to an increased risk of breast cancer. Other genetic changes, such as mutations in TP53 and PALB2, may also contribute to the development of invasive ductal carcinoma.

How is this diagnosis made?

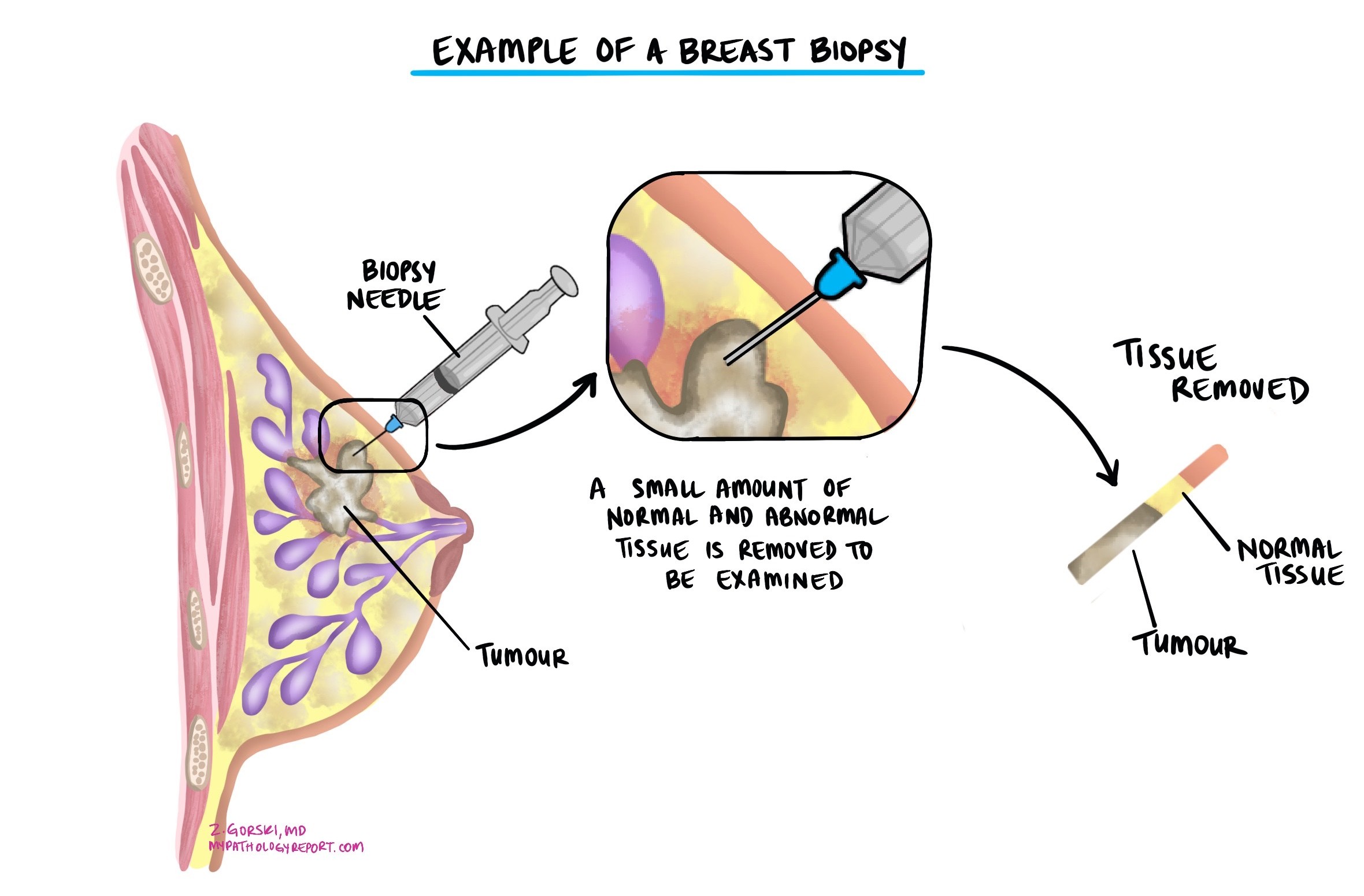

The diagnosis of invasive ductal carcinoma is usually made after a small sample of the tumour is removed in a procedure called a biopsy. The tissue is then sent to a pathologist for examination under a microscope. You may then be offered additional surgery to remove the tumour altogether.

Your pathology report for invasive ductal carcinoma

A pathology report is a medical document prepared by a pathologist, a doctor who specialises in examining tissues under the microscope. This report provides essential details about your cancer diagnosis. The type of information included in your pathology report depends on whether you had a biopsy (a small tissue sample) or surgery to remove the entire tumour. The sections below explain key terms and features commonly found in pathology reports for invasive ductal carcinoma. They will help you understand your results and their significance for your treatment and prognosis.

Nottingham histologic grade

The Nottingham histologic grade, also known as the modified Scarff-Bloom-Richardson grade, is a system used by pathologists to evaluate breast cancer under the microscope. It helps determine the aggressiveness of the tumour and provides important information for planning treatment. The grade is based on how different the cancer cells look from normal breast cells and how quickly they are growing.

To calculate the grade, pathologists examine three features of the cancer:

- Tubule formation: This measures the extent to which cancer cells form structures resembling normal breast glands. If most of the cells form tubules, the tumour gets a lower score. Fewer tubules mean a higher score.

- Nuclear pleomorphism: This describes the variation in the appearance of cancer cells’ nuclei (the part of the cell that contains DNA) compared to normal cells. The score is low if the nuclei are uniform and similar to those of normal cells. If they are very different and irregular, the score is higher.

- Mitotic count: This measures the number of cancer cells that are actively dividing. Cells that are dividing undergo a process called mitosis and are referred to as mitotic figures. A higher number of dividing cells indicates that the tumour is growing quickly, resulting in a higher score.

Each feature is scored from 1 to 3, with 1 indicating a level close to normal and 3 indicating a more abnormal level. The scores are added together to give a total score between 3 and 9, which determines the grade.

The total score places the tumour into one of three grades:

- Grade 1 (Low grade): Total score of 3 to 5. Cancer cells often resemble normal cells and typically grow at a slow rate.

- Grade 2 (Intermediate grade): Total score of 6 to 7. The cancer cells show more differences from normal and grow at a moderate rate.

- Grade 3 (High grade): Total score of 8 to 9. Cancer cells appear distinctly different from normal cells and tend to grow more rapidly.

The grade helps doctors predict how aggressive the cancer will likely be. Grade 1 cancers often grow slowly and may have a better outcome. Grade 3 cancers can grow and spread more quickly and may require more aggressive treatment. Your doctor will use the grade and other factors, such as tumour size and whether cancer is found in lymph nodes, to guide treatment decisions.

Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR)

Hormone receptors are proteins found in some breast cancer cells. The two main types tested are estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR). Cancer cells with these receptors utilise hormones such as estrogen and progesterone to promote growth and division. Testing for ER and PR helps guide treatment and predict prognosis.

Cancer cells are described as hormone receptor-positive if ER or PR is present in at least 1% of cells. These cancers often grow more slowly, are less aggressive, and typically respond well to hormone-blocking therapies, such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors (e.g., anastrozole, letrozole, or exemestane). Hormone therapy helps reduce the chance of cancer recurrence.

Your pathology report will typically include:

-

Percentage of positive cells: For example, “80% ER-positive” means 80% of cancer cells have estrogen receptors.

-

Intensity of staining: Reported as weak, moderate, or strong, this indicates the number of receptors present in the cancer cells.

-

Overall score (Allred or H-score): This combines percentage and intensity, with higher scores indicating a better response to hormone therapy.

Tumours with ER positivity between 1% and 10% are considered ER low positive. These cancers still usually respond better to hormone therapy compared to ER-negative cancers.

Understanding ER and PR status helps your doctors plan effective treatment tailored to your cancer.

HER2

HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) is a protein found on specific breast cancer cells that facilitates their growth and division. Breast cancers with extra HER2 proteins due to a change (amplification) in the HER2 gene are called HER2-positive.

HER2-positive cancers tend to be more aggressive and were once associated with a poorer prognosis. However, effective targeted therapies now significantly improve outcomes for patients with HER2-positive cancers. Knowing the HER2 status helps your doctors choose treatments specifically designed for your type of cancer, often including targeted drugs along with chemotherapy.

Two tests are commonly performed to measure HER2 in breast cancer cells: immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for HER2

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a test pathologists use to measure the amount of HER2 protein on the surface of breast cancer cells. To perform this test, pathologists use a small tissue sample from the tumour. They apply special antibodies to the tissue, which bind to HER2 proteins if they are present. These antibodies are then made visible under a microscope by adding a colored dye. By examining the intensity (strength) and amount of colour present, the pathologist determines how much HER2 protein is on the cancer cells.

Your pathology report will describe the results of HER2 IHC testing as a score ranging from 0 to 3+:

-

0 (negative): No visible staining, meaning no significant HER2 protein is detected. This indicates a HER2-negative tumour, and targeted HER2 treatments will not typically be helpful.

-

1+ (negative): Weak and incomplete staining. These tumours are still considered HER2-negative and usually don’t benefit from HER2-targeted treatments.

-

2+ (borderline or equivocal): Moderate staining, meaning the result is unclear. Additional testing, typically a FISH test, is required to determine whether the cancer is HER2-positive or HER2-negative.

-

3+ (positive): Strong and complete staining on the surface of the cancer cells. This indicates a HER2-positive breast cancer. HER2-positive cancers often grow faster but respond very well to HER2-targeted therapies like trastuzumab.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for HER2

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a test used to examine cancer cells for extra copies of specific genes, such as HER2. In breast cancer testing, FISH is usually performed after the initial HER2 IHC test gives unclear or borderline results.

To perform a FISH test, pathologists use a small tissue sample from the tumour. They add special fluorescent probes to the tissue, which attach specifically to the HER2 genes inside the cancer cells. Under a microscope, these probes glow brightly, enabling pathologists to count the number of copies of the HER2 gene present in each cell.

Your pathology report will typically describe the results of the FISH test as either:

-

Positive (Amplified): The cancer cells have extra copies of the HER2 gene. This is known as HER2-positive breast cancer. These cancers often grow more aggressively but typically respond well to targeted HER2 treatments, such as trastuzumab (Herceptin).

-

Negative (Non-amplified): The cancer cells have a normal number of HER2 gene copies. This is called HER2-negative breast cancer, meaning targeted HER2 therapies are usually not helpful.

Sometimes the report may describe the exact number of gene copies per cell (for example, an average HER2 copy number or a HER2-to-chromosome ratio). These detailed numbers help pathologists and oncologists confirm the HER2 status accurately, guiding the choice of the most effective treatment for your specific cancer type.

Micropapillary features

Micropapillary features in invasive ductal carcinoma refer to a specific pattern of cancer growth seen under the microscope. The term “micropapillary” describes small clusters of tumour cells that appear to be floating in open spaces. These features are important because cancers with micropapillary features are more likely to invade nearby lymphatic vessels and spread to lymph nodes.

If more than 90% of the tumour shows micropapillary features, it is classified as invasive micropapillary carcinoma. This is considered a distinct type of breast cancer that may require specific treatment considerations.

While cancers with micropapillary features tend to behave more aggressively, this does not always mean a worse outcome. Studies show that these tumours have a higher chance of returning in the same area or to axillary lymph nodes. Still, they do not significantly affect overall survival or the risk of the cancer spreading to distant parts of the body when compared to other types of invasive ductal carcinoma of the same size and stage.

Mucinous features

Mucinous features in invasive ductal carcinoma refer to a specific pattern in which the tumour cells are surrounded by large amounts of mucin, a gel-like substance typically found in various parts of the body. Under the microscope, these cancers appear as clusters of tumour cells floating in pools of mucin.

If more than 90% of the tumour shows mucinous features, it is classified as invasive mucinous carcinoma. This is considered a distinct type of breast cancer with unique characteristics and often a better prognosis compared to other types of invasive ductal carcinoma.

Cancers with mucinous features tend to grow more slowly and are less likely to metastasise to lymph nodes or other parts of the body. As a result, they are often associated with a more favorable outcome. However, if the tumour has a mix of mucinous and non-mucinous areas, the behaviour may depend on the proportion of mucinous features and other tumour characteristics.

Tumour size

The size of a breast tumour is important because it is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT) and because larger tumours are more likely to metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes and other parts of the body. The tumour size can only be determined after the entire tumour has been removed. For this reason, it will not be included in your pathology report after a biopsy.

Tumour extension

Invasive ductal carcinoma starts inside the breast, but the tumour may spread into the overlying skin or the muscles of the chest wall. The term tumour extension is used when tumour cells are found in the skin or muscles below the breast. Tumour extension is important because it is associated with a higher risk that the tumour will recur after treatment (local recurrence) or that cancer cells will metastasise to a distant body site, such as the lungs. It is also used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means that cancer cells have entered small blood vessels or lymphatic channels located near the tumour in the breast. Blood vessels are small tubes that carry blood to and from tissues, delivering oxygen and nutrients. Lymphatic vessels are similar but carry lymph fluid, which contains immune cells and helps remove waste from tissues. Both types of vessels can provide pathways for cancer cells to spread beyond the original tumour site.

Pathologists carefully examine tissue samples under the microscope to look for LVI. Cancer cells may appear as single cells or clusters inside these vessels, often surrounded by a clear space that marks the vessel wall. Your pathology report will typically describe LVI as “positive” (or “present”) if cancer cells are found inside these vessels, or “negative” (or “absent”) if no cancer cells are seen.

The presence of LVI is important because it suggests a higher chance that cancer will spread to nearby lymph nodes or may spread to distant parts of the body. Because of this, your medical team may recommend more aggressive treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or targeted therapy, to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence and spread.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge or border of tissue removed along with a tumour during surgery. Margins are closely examined under a microscope by a pathologist to see if any cancer cells are present at the cut edge. The status of these margins is important because it helps determine if the entire tumour was removed or if cancer cells may have been left behind in the body.

Margins are typically assessed only after a surgical procedure, such as a resection or excision, which removes the entire tumour. They are usually not described following a biopsy, as biopsies remove only a small sample of tissue, not the whole tumour. The number and type of margins described in your pathology report depend on the size and location of the tumour, as well as the type of tissue removed.

To evaluate margins, the pathologist carefully examines thin slices of the tissue under a microscope. They look closely at the edges to see if tumour cells reach the cut surface. Your pathology report will describe these results as either negative (no cancer cells seen at the margin) or positive (cancer cells present at the margin). If the margin is negative, the report may also mention the exact distance between the closest tumour cells and the cut edge, known as the margin width.

The results of the margin examination are very important for planning your treatment. A positive margin indicates that some cancer cells are likely to remain in the body, thereby increasing the risk of the cancer recurring or progressing. If you have a positive margin, your doctor may recommend further treatment, such as additional surgery to remove any remaining tumour or radiation therapy directed at the area where the positive margin was found. A negative margin, especially with a greater distance from tumour cells to the cut edge, suggests that the cancer has been entirely removed, reducing the likelihood of recurrence.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped organs that play a key role in the body’s immune system. They filter harmful substances, such as bacteria, viruses, and cancer cells, from the lymph fluid circulating throughout the body. Lymph nodes contain immune cells that help fight infections and can respond to cancer cells.

When breast cancer spreads beyond the original tumour, it often moves first into nearby lymph nodes. Because of this, pathologists carefully examine lymph nodes removed during surgery to determine whether cancer has spread. This is a critical step for understanding your cancer’s stage, planning appropriate treatment, and predicting your prognosis (the likely outcome).

In breast cancer, several types of lymph nodes may be examined:

-

Axillary lymph nodes: Located under the arm, these are the most commonly examined nodes in breast cancer cases.

-

Sentinel lymph nodes: These are usually the first few lymph nodes that cancer cells would reach from the breast. A sentinel lymph node biopsy involves removing one or a few of these nodes for testing.

-

Internal mammary lymph nodes: Located near the breastbone, these nodes are sometimes examined if cancer cells are found in other lymph nodes or if imaging tests suggest involvement.

How lymph nodes are examined

Lymph nodes removed during surgery are carefully examined under a microscope by a pathologist.

Your pathology report will provide detailed information, including:

-

Number of lymph nodes examined: The total count of lymph nodes removed and examined.

-

Number of positive lymph nodes: The number of lymph nodes containing cancer cells.

-

Size of cancer deposits: The size of the largest group of cancer cells found within any lymph node.

-

Other features: Your report may occasionally mention additional findings, such as extranodal extension, which indicates that cancer cells have spread beyond the lymph node itself.

Possible results and what they mean

Your pathology report may describe cancer cells in the lymph nodes using the following terms, depending on the size of the cancer deposits:

-

Isolated tumour cells (ITCs): Very small groups of cancer cells measuring 0.2 millimeters or less. Although these cells are detected, lymph nodes containing only isolated tumour cells are generally not considered positive for the purposes of cancer staging, and they usually have minimal impact on prognosis and treatment decisions.

-

Micrometastasis: Cancer cell clusters that measure between 0.2 millimeters and 2 millimeters. If lymph nodes contain only micrometastases, this finding is noted as “pN1mi” in your report. Micrometastases can slightly increase the risk of recurrence and may lead your doctors to consider additional treatments, such as radiation or chemotherapy, depending on other factors.

-

Macrometastasis: Larger cancer cell clusters measuring more than 2 millimeters. The presence of macrometastases indicates a greater risk that the cancer may recur or spread further. These findings typically prompt more aggressive treatment strategies, which can include additional surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or targeted therapies.

Residual cancer burden index

The residual cancer burden (RCB) index measures the amount of cancer remaining in the breast and nearby lymph nodes after neoadjuvant therapy (treatment given before surgery). The index combines several pathologic features into a single score and classifies the cancer’s response to treatment. Doctors at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center developed the RCB (http://www.mdanderson.org/breastcancer_RCB).

Here’s how the score is calculated:

- Size of the tumour bed in the breast: Pathologists measure the largest two dimensions of the area where the tumour was located, called the tumour bed. This area may contain a mix of normal tissue, cancer cells, and scar tissue from the therapy.

- Cancer cellularity: Cancer cellularity estimates the percentage of the tumour bed that still contains cancer cells. This includes both invasive cancer (cancer that has spread into surrounding tissue) and in situ cancer (cancer cells that have not spread).

- Percentage of in situ disease: Within the tumour bed, pathologists also estimate the percentage of cancer that is in situ, meaning that the cancer cells are confined to the milk ducts or lobules and have not spread into the surrounding tissue.

- Lymph node involvement: The number of lymph nodes containing cancer cells (positive lymph nodes) is counted, and the size of the largest cluster of cancer cells in the lymph nodes is also measured.

These features are combined using a standardized formula to calculate the RCB score.

Based on the RCB score, patients are divided into four categories:

- RCB-0 (pathologic complete response): No residual invasive cancer is detected in the breast or lymph nodes.

- RCB-I (minimal burden): Very little residual cancer is present.

- RCB-II (moderate burden): A moderate amount of cancer remains.

- RCB-III (extensive burden): A large amount of cancer remains in the breast or lymph nodes.

The RCB classification helps predict a patient’s likelihood of staying cancer-free after treatment. Patients with an RCB-0 classification typically have the best outcomes, with the highest chances of long-term survival without recurrence. As the RCB category increases from RCB-I to RCB-III, the risk of cancer recurrence increases, which may prompt additional treatments to reduce this risk.

Pathologic stage for invasive ductal carcinoma

The pathologic staging system for invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast helps doctors understand how far the cancer has spread and plan the best treatment. The system mainly uses the TNM staging, which stands for Tumor, Nodes, and Metastasis. Early-stage cancers (like T1 or N0) might only require surgery and possibly radiation, while more advanced stages (like T3 or N3) may need a combination of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies. Proper staging ensures that patients receive the most effective treatments based on the extent of their disease, which can improve survival rates and quality of life.

Tumour stage (pT)

This feature examines the size and extent of the breast tumour. The tumour is measured in centimetres, and its growth beyond the breast tissue is assessed.

T0: No evidence of primary tumour. This means no tumour can be found in the breast.

T1: The tumour is 2 centimetres or smaller in greatest dimension. This stage is further subdivided into:

- T1mi: Tumour is 1 millimetre or smaller.

- T1a: Tumour is larger than 1 millimetre but not larger than 5 millimetres.

- T1b: Tumour is larger than 5 millimetres but not larger than 10 millimetres.

- T1c: Tumour is larger than 10 millimetres but not over 20 millimetres.

T2: The tumour is larger than 2 centimetres but not larger than 5 centimetres.

T3: The tumour is larger than 5 centimetres.

T4: The tumour has spread to the chest wall or skin, regardless of its size. This stage is further subdivided into:

- T4a: Tumour has invaded the chest wall.

- T4b: Tumour has spread to the skin, causing ulcers or swelling.

- T4c: Both T4a and T4b are present.

- T4d: Inflammatory breast cancer, characterized by redness and swelling of the breast skin.

Nodal stage (pN)

This feature examines if the cancer has spread to the nearby lymph nodes, which are small, bean-shaped structures found throughout the body.

N0: No cancer is found in the nearby lymph nodes.

N0(i+): Isolated tumour cells only.

N1: Cancer has spread to 1 to 3 axillary lymph nodes (under the arm).

- N1mi: Micrometastases only.

- N1a: Metastases in 1-3 axillary lymph nodes, at least one metastasis larger than 2.0 mm.

- N1b: Metastases in ipsilateral internal mammary sentinel nodes, excluding ITCs

N2: Cancer has spread to:

- N2a: 4 to 9 axillary lymph nodes.

- N2b: Internal mammary lymph nodes without involvement of axillary lymph nodes.

N3: Cancer has spread to:

- N3a: 10 or more axillary lymph nodes or two infraclavicular lymph nodes (below the collarbone).

- N3b: Internal mammary lymph nodes and axillary lymph nodes.

- N3c: Supraclavicular lymph nodes (above the collarbone).

Prognosis

The prognosis for a patient diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma depends on several factors, including the stage of the disease, tumour characteristics, and treatment options. Below are some of the most important factors that influence outcomes:

- Tumour stage and size: The stage of the cancer, which describes how far it has spread, is one of the most important predictors of survival. Early-stage tumours that are small and confined to the breast have a better prognosis. For example, the 5-year survival rate for localised breast cancer is over 95%. However, survival decreases if the cancer spreads to lymph nodes or distant organs.

- Tumour grade: The grade of the tumour describes how abnormal the cancer cells look under a microscope. High grade tumours tend to grow and spread more quickly and may have a less favourable outcome.

- Hormone receptor and HER2 status: Hormone receptor-positive cancers, which grow in response to estrogen or progesterone, often have a better prognosis because they can be treated with hormone therapies. HER2-positive cancers are more aggressive but can respond well to targeted treatments like trastuzumab. Triple-negative breast cancers (lacking estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors) are more challenging to treat and may have a less favourable prognosis.

- Lymphovascular invasion: Cancer cells in blood vessels or lymphatic vessels near the tumour increase the risk of the cancer spreading and may influence treatment decisions.

- Pathological margins: The completeness of tumour removal during surgery affects the risk of recurrence. Tumours that are entirely removed with no cancer cells at the margins (edges of the surgical specimen) have a lower risk of local recurrence.

- Ki-67 proliferation index: The Ki-67 index measures how quickly cancer cells are dividing. A higher Ki-67 index suggests a more aggressive tumour and may influence decisions about chemotherapy.

- Genetic testing: Some patients may benefit from genetic testing of the tumour to help predict the risk of recurrence. Tests such as the 21-gene recurrence score or 70-gene signature can help identify patients who may benefit from additional treatments, such as chemotherapy.

- Androgen receptor (AR) status: Androgen receptor (AR) expression has been associated with better outcomes in early-stage breast cancer. Studies have shown that patients whose tumours express AR may have improved disease-free survival and overall survival. However, the role of AR in breast cancer, particularly in estrogen receptor (ER)-positive and ER-negative tumours, is complex. While AR may hold promise as a target for hormone or androgen-based therapies, the evidence is still under investigation. As a result, AR testing is not routinely performed but may be considered in specific clinical situations.

- Response to neoadjuvant therapy: The response to neoadjuvant therapy, which is treatment given before surgery, can provide important prognostic information. Achieving a pathological complete response (no remaining cancer detected after treatment) is a strong predictor of better outcomes, especially for HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancers. For patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy, the residual cancer burden index can be used to estimate the risk of recurrence. This index considers factors such as tumour size, lymph node involvement, and the extent of remaining cancer, and guides further treatment decisions.