by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Trevor Flood MD FRCPC

August 20, 2024

Non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma of the penis (also known as HPV-independent squamous cell carcinoma) is a rare type of cancer that arises from the squamous cells lining the skin of the penis. Unlike the more common form of penile squamous cell carcinoma associated with human papillomavirus (HPV), this type of cancer develops independently of the virus.

What are the symptoms of non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma of the penis?

The symptoms of non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma of the penis can include a lump or sore on the penis, often located on the head or foreskin. This lesion may be painless in the early stages but can become painful or bleed as it grows. Other symptoms can include difficulty retracting the foreskin, changes in the skin colour or texture, and, in more advanced cases, swelling in the groin due to the involvement of nearby lymph nodes.

What causes non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma of the penis?

Non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma of the penis is not related to infection with HPV. Instead, it is thought to be caused by chronic irritation of the penile skin. Factors that may increase the risk include poor genital hygiene, chronic balanitis (inflammation of the foreskin), smoking, and conditions like phimosis, where the foreskin cannot be retracted.

Chronic inflammation of the penile skin is associated with a precancerous condition called differentiated penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN), which, if left untreated, can lead to non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma. Circumcision at an early age reduces the risk of developing this type of cancer, possibly due to decreased irritation and better hygiene.

How is the diagnosis of non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma of the penis made?

The diagnosis of non-HPV SCC of the penis is usually made after a small piece of tissue is removed in a procedure called a biopsy. The tissue is then sent to a pathologist for examination under the microscope. After the diagnosis, your doctor may recommend removing the entire tumour. If removed, the tumour will also be sent to a pathologist for examination under the microscope.

Histologic types of non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma

Non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma of the penis can be classified into four main histologic types, each with distinct microscopic features and varying prognosis.

The four histologic types of non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma of the penis are:

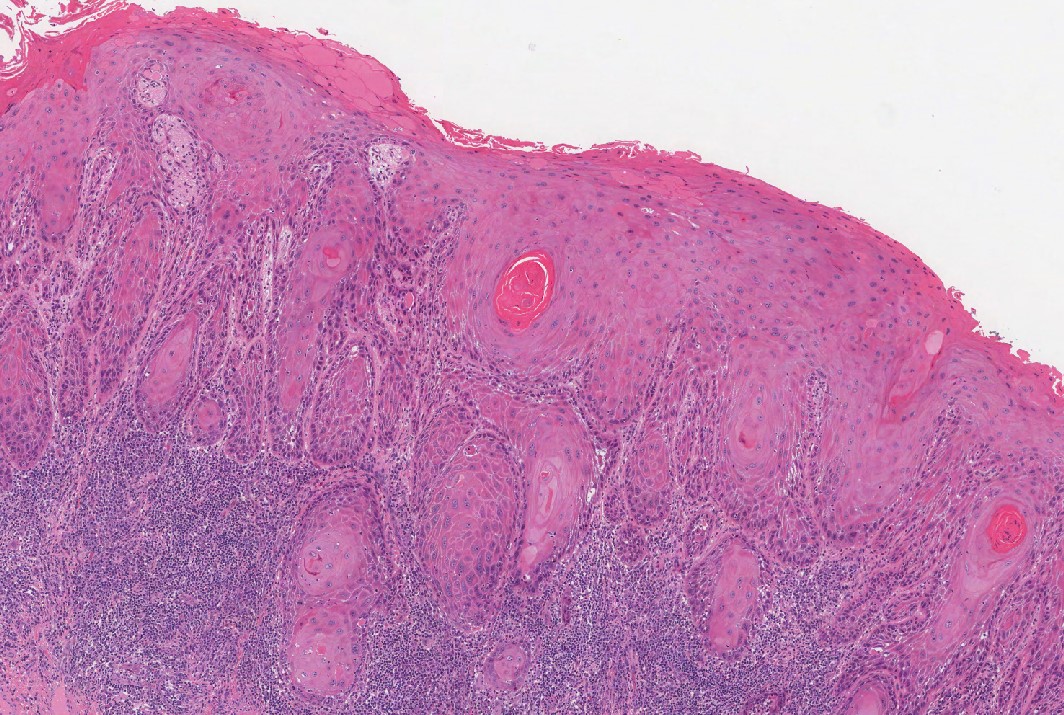

- Usual type squamous cell carcinoma: This is the most common form of non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma. Under the microscope, the tumour cells resemble squamous cells, forming irregular nests and sheets. Keratin pearls, which are circular structures made of keratin, are often seen. This type has an intermediate level of aggressiveness, with the potential to invade local tissues and spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- Verrucous carcinoma: Verrucous carcinoma is a low grade variant that grows slowly and tends to have a more favorable prognosis. Microscopically, it shows broad, pushing borders with a wart-like (verrucous) appearance. The tumour cells are well differentiated, meaning they closely resemble normal squamous cells. Verrucous carcinoma may be locally invasive but it will not spread to lymph nodes.

- Papillary squamous cell carcinoma: This variant is characterized by finger-like projections (papillae) seen under the microscope. The tumour cells are arranged in complex fronds that extend outward. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma tends to behave similarly to the usual type but may be more challenging to distinguish from benign papillomas. It generally has a moderate potential for invasion and metastasis.

- Spindle cell (sarcomatoid) squamous cell carcinoma: This is the most aggressive histologic type. It is characterized by spindle-shaped tumour cells that resemble those seen in sarcomas, cancers originating in soft tissues. This histologic type is highly aggressive, with a greater tendency to invade surrounding tissues and to metastasize to distant organs. The prognosis for spindle cell carcinoma is generally poorer compared to other types.

Grade

Non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma of the penis, specifically the usual type, is divided into three grades: well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated. These grades reflect how closely the tumour cells resemble normal squamous cells and the growth pattern.

- Well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma: In this grade, the tumour cells closely resemble normal squamous cells. The cells are arranged in well-formed nests or sheets, and keratin pearls are often prominent. Well differentiated tumors tend to grow more slowly and are less likely to invade deeply or metastasize.

- Moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma: This grade shows an intermediate level of differentiation. The tumour cells are more irregular in shape and size, and while they still produce keratin, their structures are less organized. Compared to well differentiated tumours, these tumors have a higher potential for local invasion and spread.

- Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma: In poorly differentiated tumours, the cells look very abnormal and do not closely resemble normal squamous cells. The architecture is disorganized, and keratin production is often minimal. These tumours are more aggressive, with a higher likelihood of deep tissue invasion and metastasis.

The grade of non-HPV squamous cell carcinoma is important because it helps predict the behaviour of the tumour. Well differentiated tumors tend to be less aggressive, while poorly differentiated tumours are associated with a more aggressive clinical course and a higher risk of spreading to other body parts. The grade plays a key role in determining the treatment plan and the overall prognosis for the patient.

Depth of invasion

Non-HPV SCC starts from squamous cells found in the skin on the surface of the penis. As the tumour grows, the cancer cells can spread into the layers of tissue below the skin. These layers include the lamina propria, dermis, dartos fascia, corpus spongiosum, corpus cavernosum, tunica albuginea, and Buck’s facia. The term depth of invasion describes how far the cancer cells have spread from the epithelium into the layers of tissue below.

The depth of invasion is important because tumours with a greater depth of invasion are more likely to spread to lymph nodes in the pelvis or abdomen. The depth of invasion is also used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion is a term pathologists use to describe cancer cells attached to or inside a nerve. Nerves are like long wires made up of groups of cells called neurons. Nerves are found all over the body and they are responsible for sending information (such as temperature, pressure, and pain) between your body and your brain. Perineural invasion is important because the cancer cells can use the nerve to spread into surrounding organs and tissues. This increases the risk that the tumour will regrow after treatment.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells were seen inside of a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. Lymphovascular invasion is important because cancer cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other parts of the body such as lymph nodes or the lungs. For non-HPV SCC of the penis lymphovascular invasion is also used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

Margins

A margin is any tissue cut by the surgeon to remove the tumour from your body. The margins described in your report will depend on the tumour’s location and the type of surgery performed. Your report will only describe margins after the entire tumour has been removed.

A negative margin means no cancer cells were seen at any of the cut edges of tissue. A margin is called positive when cancer cells are at the cut tissue’s very edge. A positive margin is associated with a higher risk of the tumour growing back in the same location after treatment.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs located throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread from the tumour to a lymph node through lymphatic vessels located in and around the tumour. This movement is called metastasis. Lymph nodes from the inguinal canal or pelvis may be removed to look for cancer cells. This information is then used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN).

If lymph nodes were removed, your pathologist will examine each one for cancer cells. Lymph nodes that contain cancer cells are called positive, while those that do not contain any cancer cells are called negative. Most reports include the total number of lymph nodes examined and the number, if any that contain cancer cells.