By Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

September 25, 2024

Spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma is a rare type of cancer that starts in skeletal muscle tissue, which is responsible for voluntary movements. It can affect people of all ages, but the features of this cancer can vary between children and adults. This type of rhabdomyosarcoma is named for the unique appearance of its cells under the microscope. The “spindle cell” variant has long, narrow cells, while the “sclerosing” variant involves cells arranged in a dense, fibrous (sclerosing) pattern.

What are the symptoms of spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma?

The symptoms depend on the location of the tumour, but common signs include:

- A lump or mass, which may or may not be painful.

- Swelling in the area of the tumour.

- Difficulty using a part of the body where the tumour is located.

- Symptoms related to compression of nearby structures, such as difficulty breathing or swallowing, if the tumour is in the head, neck, or chest.

What causes spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma?

The exact cause of spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma is not fully understood. However, some cases are associated with genetic changes that contribute to the development and growth of cancerous cells. These genetic changes differ based on the patient’s age and other factors.

What genetic changes are associated with spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma?

The genetic abnormalities found in spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma can be divided into three groups:

- Congenital/infantile spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma: This group is typically found in infants and young children and involves gene fusions. These fusions occur when two genes that normally function separately become abnormally joined together. Some of the gene fusions seen in this group include SRF-NCOA2, TEAD1-NCOA2, VGLL2-NCOA2, and VGLL2-CITED2. These genetic changes promote the development of cancerous cells.

- Adolescents and adults: In many cases of spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma found in adolescents, young adults, and some older adults, a mutation in the MYOD1 gene is commonly found. This mutation, called p.Leu122Arg, affects the part of the gene that helps control muscle cell growth and function. The mutation causes the gene to stop working properly, allowing cancer cells to grow unchecked.

- Other cases: Some cases of spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma do not show any recurrent genetic alterations, meaning no specific genetic changes are consistently found in these tumours.

Spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma in adults

In adults, spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma often shows the MYOD1 mutation, which contributes to the development of cancer. These tumours are most commonly found in the arms, legs, and trunk. The prognosis for adults with this type of rhabdomyosarcoma can vary depending on the size and stage of the tumour at diagnosis. Treatment usually involves surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, but the overall prognosis tends to be worse than for children with this type of cancer.

Spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma in children

In children, especially infants and young children, spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma is more likely to be associated with gene fusions involving VGLL2, SRF, TEAD1, NCOA2, and CITED2. These tumours are often found in the head and neck or the genitourinary tract. Children with this type of rhabdomyosarcoma generally have a better prognosis than adults, especially when the tumour is caught early and treated with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

How is this diagnosis made?

The first diagnosis of spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma is usually made after a small tumour sample is removed in a biopsy procedure. The biopsy tissue is then sent to a pathologist, who examines it under a microscope. After a pathologist makes a diagnosis of spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma, patients are often treated first with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, followed by surgery. The tumour is then removed completely as a resection specimen and sent to pathology for examination.

What are the microscopic features of spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma?

When a pathologist examines spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma under a microscope, they may see a variety of patterns depending on the specific type:

- Spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma: This variant is made up of long, narrow cells that grow in bundles or fascicles, sometimes forming a pattern that resembles other types of soft tissue cancers, such as leiomyosarcoma or fibrosarcoma. The cancer cells often have pale pink cytoplasm, and their nuclei (the central part of the cell that contains genetic material) are usually oval or elongated. Mitotic figures (signs that the cells are dividing) and nuclear atypia (abnormal shapes and sizes of the nuclei) are common. In some areas, there may be undifferentiated cells that look more primitive, along with rhabdomyoblasts, which are cells that resemble immature muscle cells.

- Sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma: This variant shows dense, fibrous tissue (sclerosis) throughout the tumour. The tumour cells may be arranged in cords, nests, or other patterns, sometimes resembling blood vessels. There is often a lot of intervening sclerosis, which creates a hardened, scar-like appearance in the tumour.

What other tests are used to confirm the diagnosis?

Several additional tests help pathologists confirm the diagnosis of spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma:

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): This test helps detect specific proteins present in rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Pathologists use antibodies to stain for proteins like desmin, MYOD1, and myogenin, which are common in muscle tissue and help confirm the diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma.

- Molecular tests: Molecular tests, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and next-generation sequencing (NGS), can look for specific genetic changes in the tumour cells. FISH can detect gene fusions, while NGS can identify mutations, such as the MYOD1 mutation in spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma. These tests are important for diagnosing the specific subtype and guiding treatment decisions.

Grade

Pathologists currently do not provide a grade for spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma.

Tumour size

Tumour size is important because tumours less than 5 cm are less likely to spread to other body parts and are associated with a better prognosis. Tumour size is also used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

Tumour extension

Most spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcomas start inside a muscle, but the tumour can grow into other organs or tissues outside the muscle. This is called tumour extension. Your pathologist will examine samples of the surrounding organs and tissues under the microscope for tumour cells. Any surrounding organs or tissue that contain tumour cells will be described in your report. Tumour extension into surrounding organs or tissues increases the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

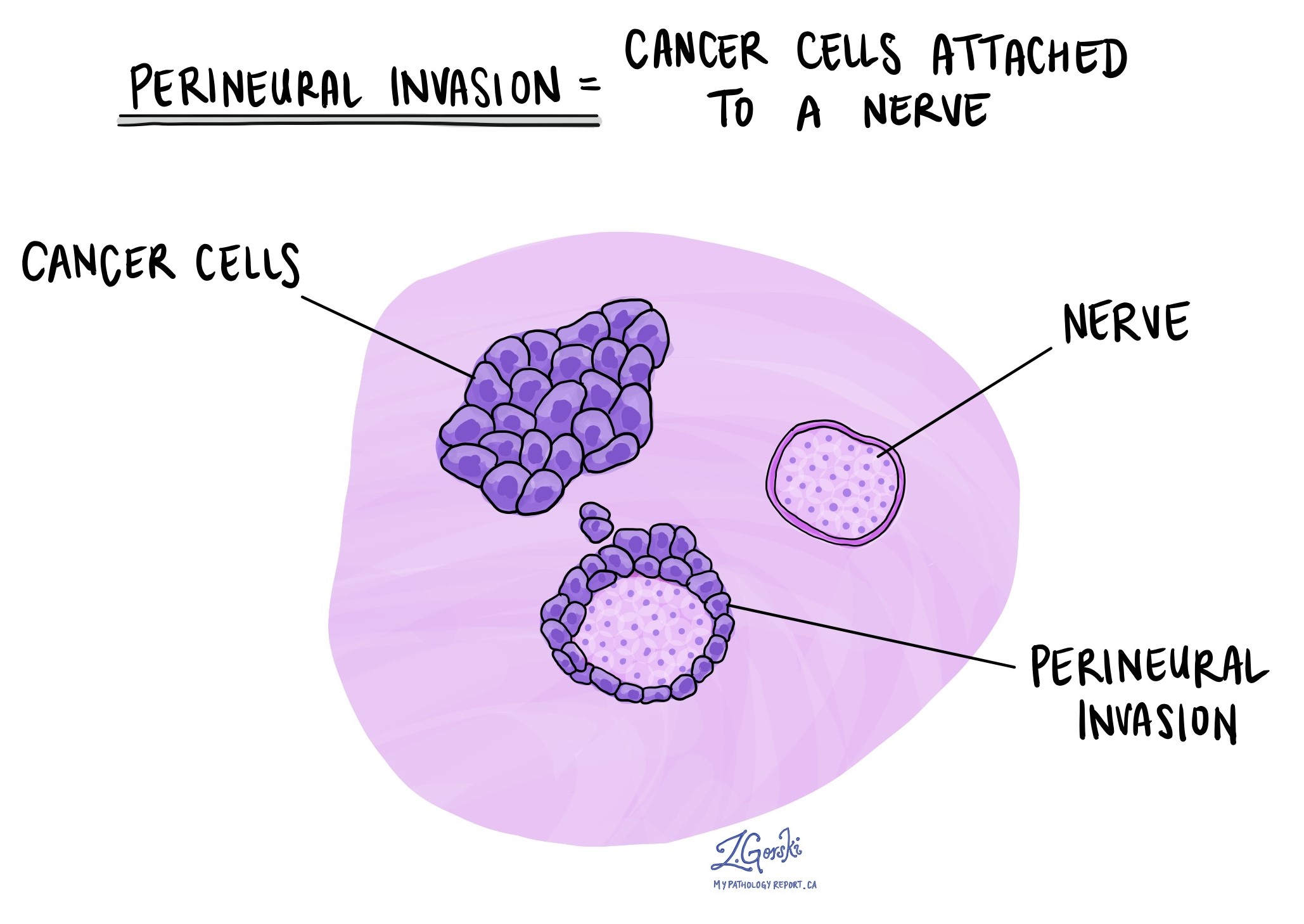

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion means that tumour cells were seen attached to a nerve. Nerves are found all over the body and are responsible for sending information (such as temperature, pressure, and pain) between the body and the brain. Perineural invasion is important because tumour cells attached to a nerve can spread into surrounding tissues by growing along the nerve. This increases the risk that the tumour will regrow after treatment.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion means tumour cells are seen inside a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long, thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it increases the risk of the tumour metastasising or spreading to other body parts, such as lymph nodes or the lungs.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure, like an excision or resection, that removes the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was fully removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

Treatment effect

If you have been diagnosed with spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma on a biopsy, you may be offered chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy before the operation to remove the tumour. If you have received either of these treatments before your surgery, your pathologist will examine all the tissue sent to pathology to see how much of the tumour is still alive (viable).

Different systems are used to describe the effects of treatment for pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma. Most commonly, your pathologist will describe the percentage of dead tumour. Pathologists use the word necrosis to describe dead (non-viable) tumours. A tumour showing 90% or more therapy response (meaning 90% of the tumour is dead and 10% or less alive) is considered an excellent response to therapy and is associated with a better prognosis.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread through small lymphatic vessels from tumours to lymph nodes. For this reason, lymph nodes are commonly removed and examined under a microscope to look for cancer cells. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to another part of the body, such as a lymph node, is called a metastasis.

Cancer cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour, although lymph nodes far away can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are only typically removed if they are enlarged and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancer cells in them.

If any lymph nodes were removed from your body, they will be examined under the microscope by a pathologist, and the results of this examination will be described in your report. The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information determines the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy, is required.

Some helpful definitions:

- Positive: Positive means that cancer cells were found in the lymph node being examined.

- Negative: Negative means that no cancer cells were found in the lymph node being examined.

- Deposit: The term deposit describes a group of cancer cells inside a lymph node. Some reports include the size of the largest deposit. A similar term is “focus”.

- Extranodal extension: Extranodal extension means that the tumour cells have broken through the capsule on the outside of the lymph node and have spread into the surrounding tissue.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

Tumours in adults are given a pathologic stage based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. The TNM system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis. Tumours that start in the head and neck are not staged using this system.

Tumours in children are given a pathologic stage based on a modified TNM staging system (the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group grouping system). This system uses information about the location of the tumour and the type of surgery performed to determine the final pathologic stage. All of this information is then combined to determine the risk of cancer coming back in the future.

Tumour stage (pT) for spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma in adults

The method for determining the tumour stage depends on the area of the body involved. For example, a 5-centimetre tumour that starts in the chest will be given a different stage than a tumour that begins deep in the back of the abdomen (the retroperitoneum). However, in most body sites, the tumour stage includes the tumour size and whether the tumour has grown into surrounding body parts.

Chest, back, or stomach and the arms or legs (trunk and extremities)

- T1 – The tumour is no greater than 5 centimetres in size.

- T2 – The tumour is between 5 and 10 centimetres in size.

- T3 – The tumour is between 10 and 15 centimetres in size.

- T4 – The tumour is greater than 15 centimetres in size.

Abdomen and organs inside the chest (thoracic visceral organs)

- T1 – The tumour is only seen in one organ.

- T2 – The tumour has grown into the connective tissue surrounding the organ from which it started.

- T3 – The tumour has grown into at least one other organ.

- T4 – Multiple tumours are found.

Retroperitoneum (the space at the very back of the abdominal cavity)

- T1 – The tumour is no greater than 5 centimetres in size.

- T2 – The tumour is between 5 and 10 centimetres in size.

- T3 – The tumour is between 10 and 15 centimetres in size.

- T4 – The tumour is greater than 15 centimetres in size.

Nodal stage (pN) for spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma in adults

Spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma is given a nodal stage of 0 or 1 based on the presence of tumour cells in a lymph node. If no tumour cells are seen in any lymph nodes examined, the nodal stage is N0. If tumour cells are seen in any of the lymph nodes examined, the nodal stage becomes N1.

About this article

Doctors wrote this article to help you read and understand your pathology report. Contact us with any questions about this article or your pathology report. Read this article for a more general introduction to the parts of a typical pathology report.