by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

July 26, 2025

Adenocarcinoma of the stomach, also called gastric cancer, is a type of cancer that starts in the gland-forming cells that line the inside surface of the stomach. It is the most common form of stomach cancer, making up about 90 to 95 percent of all cases. The outlook for people diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma depends on how abnormal the cancer cells look (called histologic grade), how far the cancer has spread (called stage), and whether cancer cells are found in nearby lymph nodes.

What causes adenocarcinoma of the stomach?

Several environmental and genetic factors are linked to gastric adenocarcinoma. These include:

-

Infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a type of bacteria that damages the stomach lining.

-

Infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

-

Smoking.

-

Diets low in fruits and vegetables or high in salt-preserved foods.

-

A family history of gastric cancer.

-

Inherited genetic changes in genes such as CDH1 (associated with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer) or APC (associated with familial adenomatous polyposis).

What are the symptoms of gastric adenocarcinoma?

Many people with early-stage stomach cancer have no symptoms. As the cancer grows, symptoms may include:

-

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia).

-

Feeling full quickly when eating.

-

Unexplained weight loss.

-

Stomach pain or discomfort.

-

Nausea or vomiting.

-

Vomiting blood or passing black stools (a sign of bleeding).

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma is usually made with a biopsy taken during an endoscopy. During this procedure, your doctor uses a flexible tube with a camera to look inside your stomach and remove small tissue samples called biopsies for examination under a microscope by a pathologist. Imaging studies like CT scans, MRIs, or endoscopic ultrasound may also be performed to help assess the size of the tumor and whether it has spread.

Histologic types of gastric adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinomas of the stomach are grouped based on how the cancer cells look under the microscope. These histologic types can provide important clues about how the cancer might behave.

Tubular adenocarcinoma

This is the most common type. It is made of irregularly shaped glands that resemble normal stomach tissue but look disorganized and often grow into deeper layers of the stomach.

Intestinal type adenocarcinoma

These tumors resemble the cells found in the intestine. They often develop after chronic stomach inflammation and may be associated with intestinal metaplasia, a precancerous change in the stomach lining. These tumors form glands and are usually easier to identify under the microscope.

Papillary adenocarcinoma

These tumors form finger-like projections called papillae with a core of connective tissue covered by cancer cells. They tend to grow slowly and are usually more well differentiated.

Mucinous adenocarcinoma

These tumors produce large amounts of mucus, which collects in pools between the cancer cells. If more than 50% of the tumor is made up of mucus, it is considered mucinous. This type may spread more easily and behave more aggressively.

Diffuse type and poorly cohesive adenocarcinoma

In these tumors, the cancer cells spread widely through the stomach wall without forming glands. The cells are often scattered and poorly connected to one another. These cancers are usually more difficult to detect and treat and are more likely to spread early.

Signet ring cell carcinoma

This is a specific form of poorly cohesive adenocarcinoma. The cancer cells have a large vacuole that pushes the nucleus to one side, giving them a signet ring appearance. These tumors tend to behave aggressively compared to other types of adenocarcinoma of the stomach.

Histologic grade

Histologic grade describes how different the cancer cells look compared to normal stomach cells when examined under the microscope. It is an important part of your pathology report because it helps predict how the tumour is likely to behave.

Tumours that look more like normal cells (well differentiated) tend to grow more slowly and are less likely to spread to other parts of the body. In contrast, tumours that look very abnormal (poorly differentiated or undifferentiated) tend to grow more quickly, are more aggressive, and are more likely to spread to lymph nodes or distant organs.

Adenocarcinoma of the stomach is graded based on how much of the tumour is made up of glands:

-

Well differentiated (grade 1): More than 95% of the tumour forms glands.

-

Moderately differentiated (grade 2): 50 to 95% of the tumour forms glands.

-

Poorly differentiated (grade 3): Less than 50% of the tumour forms glands.

-

Undifferentiated: No glands are seen in the tumour.

Your pathology report will include this grade and it will help your doctor determine the likelihood of the cancer spreading or returning, as well as the need for additional treatment after surgery.

Depth of invasion and pathologic stage (pT)

Adenocarcinoma of the stomach starts in the innermost layer of the stomach wall, called the mucosa. As it grows, the tumor may invade deeper layers of the stomach and even nearby organs.

The stomach wall is made up of several distinct layers:

-

Mucosa – The innermost lining where the tumour starts. It includes the epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae.

-

Submucosa – A supportive layer of connective tissue below the mucosa.

-

Muscularis propria – A thick muscle layer that contracts to help move food through the stomach.

-

Subserosal connective tissue – Tissue just beneath the outer surface.

-

Serosa – The outermost layer covering most of the stomach.

The pathologist carefully examines the tissue under the microscope to determine how far the cancer has spread into the stomach wall. This is called the depth of invasion and it is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT), which is part of the TNM staging system.

The depth of invasion is one of the most important features in your report because:

-

Tumours that invade deeper layers are more likely to spread to lymph nodes or distant organs.

-

It helps determine the overall stage and the type of treatment needed.

The pathologic tumour stage (pT) for gastric adenocarcinoma is divided into the following groups:

-

T1a: Tumour is limited to the mucosa.

-

T1b: Tumour has spread into the submucosa.

-

T2: Tumour has spread into the muscularis propria.

-

T3: Tumour has reached the subserosal soft tissue.

-

T4a: Tumour has gone through the serosa.

-

T4b: Tumour has spread into nearby organs such as the spleen, pancreas, or colon.

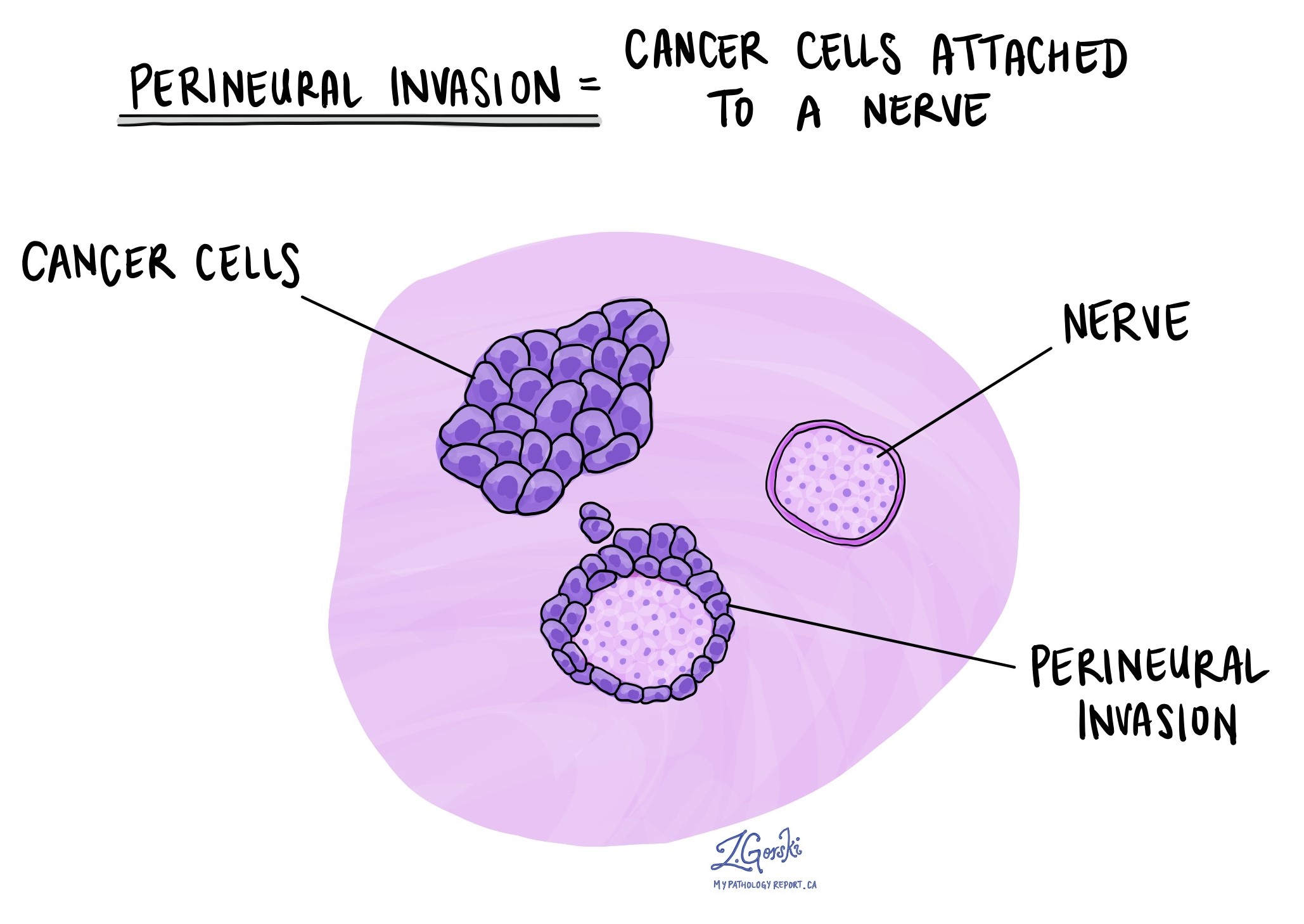

What is perineural invasion?

Perineural invasion (PNI) means cancer cells are growing along or around nerves. This is an aggressive feature that may increase the chance of cancer spreading. If present, it will be described in your pathology report.

What is lymphovascular invasion?

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means that cancer cells are seen inside blood vessels or lymphatic vessels near the tumor. This increases the risk that cancer may spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body.

Mismatch repair proteins (MMR)

Mismatch repair proteins (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6) are part of the cell’s natural system for fixing mistakes in DNA. If one or more of these proteins is lost or not working properly, the tumour may accumulate genetic errors that can lead to cancer.

Pathologists test for MMR proteins using a method called immunohistochemistry (IHC). This test uses special antibodies that bind to the MMR proteins in tumour cells. When the stain is applied, the pathologist checks whether each of the four proteins is present or absent:

-

Retained (normal) – The protein is present and the MMR system appears to be working.

-

Lost (abnormal) – The protein is missing, which suggests the MMR system is not working properly.

Loss of MMR protein expression can happen in two ways:

-

Sporadic (non-inherited) – Often caused by methylation of the MLH1 gene promoter.

-

Inherited – Due to a genetic condition called Lynch syndrome.

Loss of MMR proteins is important for two reasons:

-

It may suggest a better response to immunotherapy, such as checkpoint inhibitors.

-

It may indicate a genetic syndrome (Lynch syndrome), especially if the patient is younger or has a family history of cancer. In such cases, genetic counseling may be recommended.

HER2

HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) is a protein that helps cells grow and divide. In some stomach cancers, the HER2 gene becomes overactive and produces too much of the HER2 protein. This is called HER2-positive cancer.

HER2-positive stomach cancers tend to grow faster and may be more aggressive. However, targeted therapies like trastuzumab (Herceptin) can be very effective in treating these cancers. Knowing your tumor’s HER2 status helps your doctors decide if these targeted treatments should be part of your care plan.

How is HER2 tested?

Two tests are commonly used to check HER2 status:

-

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) – Measures the amount of HER2 protein on the surface of cancer cells.

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) – Measures the number of HER2 gene copies in the cancer cells.

HER2 immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC is a laboratory test that uses special stains to detect HER2 protein on the surface of tumor cells. Pathologists examine the stained tissue under a microscope and assign a score:

-

0 (negative) – No HER2 protein seen. This is considered HER2-negative, and targeted HER2 therapy is not usually helpful.

-

1+ (negative) – Weak or faint staining. Also considered HER2-negative.

-

2+ (equivocal or borderline) – Moderate staining. The result is unclear, and a second test (FISH) is needed.

-

3+ (positive) – Strong staining. This is HER2-positive, and patients may benefit from HER2-targeted therapy.

HER2 fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

If the IHC result is 2+ (equivocal or borderline), your pathologist may perform a FISH test to look more closely at the HER2 gene inside the tumor cells. This test uses special fluorescent markers that glow under the microscope to show how many HER2 gene copies are present.

-

Positive (amplified) – Too many HER2 gene copies. The cancer is HER2-positive and may respond well to HER2-targeted therapy.

-

Negative (non-amplified) – A normal number of HER2 gene copies. This means the cancer is HER2-negative, and HER2-targeted therapy is unlikely to help.

Sometimes, your report may include additional details like a HER2-to-chromosome ratio or the average number of HER2 gene copies per cell. These numbers help confirm the HER2 status more precisely.

Lymph nodes and pathologic nodal stage (pN)

Lymph nodes are small immune organs that filter lymphatic fluid and trap abnormal cells. In gastric cancer, cancer cells can spread to nearby lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels. During surgery, your surgeon will typically remove lymph nodes surrounding the stomach to see if they contain cancer cells.

These lymph nodes may include:

-

Perigastric lymph nodes – Around the stomach.

-

Celiac lymph nodes – Near the main artery that supplies the stomach.

-

Peripancreatic and splenic nodes – If the tumour is near the pancreas or spleen.

After removal, the lymph nodes are examined under a microscope. Your pathology report will describe whether any of the lymph nodes contain cancer cells (positive) or are free of cancer (negative). If tumour cells have spread outside the lymph node capsule into surrounding tissue, the report may mention extranodal extension.

The number of lymph nodes involved is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN):

-

pNX – No nodes submitted or examined.

-

pN0 – No regional lymph node metastasis.

-

pN1 – Metastasis in 1 to 2 regional lymph nodes.

-

pN2 – Metastasis in 3 to 6 regional lymph nodes.

-

pN3a – Metastasis in 7 to 15 regional lymph nodes.

-

pN3b – Metastasis in 16 or more regional lymph nodes.

The pN stage is essential in determining the overall stage of cancer and influences decisions about additional treatments like chemotherapy or immunotherapy.

Margins

Margins are the edges of tissue removed during surgery. A negative margin means no cancer cells are seen at the edge of the tissue, suggesting the tumour was completely removed. A positive margin means cancer cells are found at the edge, which may mean some tumour remains in the body.

For stomach cancer, several margins may be described in the pathology report:

-

Proximal margin – The edge of the stomach closest to the esophagus.

-

Distal margin – The edge closest to the small intestine (duodenum).

-

Radial margin – The outermost surface of the stomach (especially important for tumours growing outward).

-

Omental margins – If the omentum (a fat pad near the stomach) is removed, the pathologist may also examine its edges.

If all margins are negative, the tumour is considered completely removed. If any margin is positive, additional treatment may be needed.

Questions to ask your doctor

Here are some questions you can ask your doctor to better understand your diagnosis and treatment options:

-

What type of gastric adenocarcinoma do I have?

-

What is the histologic grade of my tumour and how does it affect my prognosis?

-

How deeply has the tumour grown into the wall of the stomach?

-

Have any lymph nodes tested positive for cancer, and what is my nodal stage (pN)?

-

Were the surgical margins negative? Was the entire tumour removed?

-

Did the tumour show perineural invasion or lymphovascular invasion?

-

Was my tumour tested for HER2? If so, what were the results?

-

Was mismatch repair testing done? Do the results suggest Lynch syndrome or potential benefit from immunotherapy?

-

What is my overall stage and what treatment options are recommended?

-

Should I see a genetic counselor based on my results?