by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

September 7, 2024

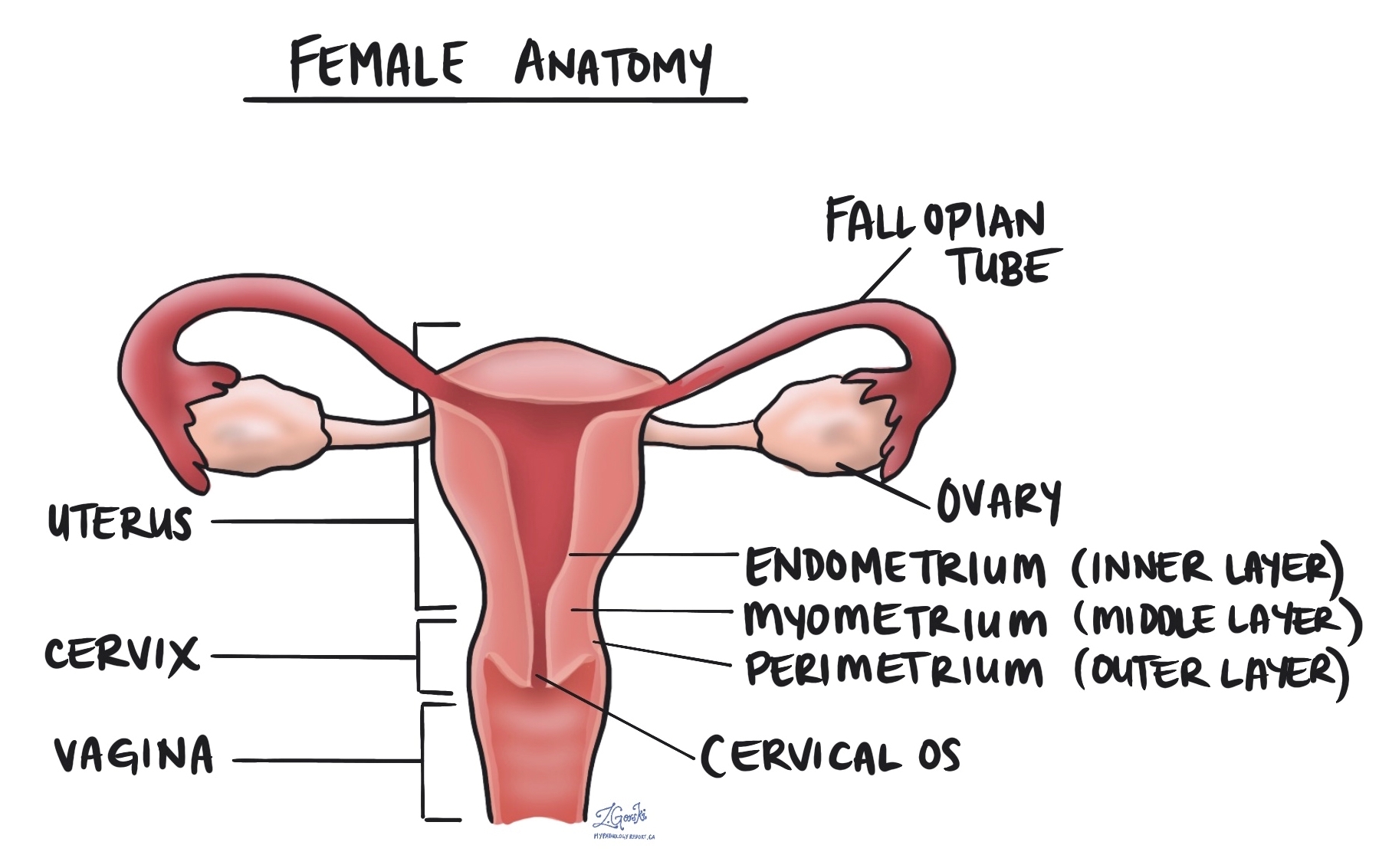

Endometrial endometrioid carcinoma is a type of cancer that starts in the endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus. It is the most common type of endometrial cancer and typically affects women over the age of 50 years. Endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma is believed to develop from a pre-cancerous condition called atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

What are the symptoms of endometrial endometrioid carcinoma?

The most common symptoms of endometrial endometrioid carcinoma include:

- Abnormal uterine bleeding. This may include bleeding between periods or after menopause.

- Pelvic pain or discomfort.

- Unusual vaginal discharge.

- Pain during intercourse.

If you experience any of these symptoms, it’s important to consult a doctor for further evaluation.

What causes endometrial endometrioid carcinoma?

The exact cause of endometrial endometrioid carcinoma is not fully understood, but several risk factors may contribute to its development, including:

- Hormonal imbalances: Increased estrogen levels, especially without the balancing effect of progesterone, can lead to abnormal cell growth in the endometrium.

- Obesity: Excess fat tissue can raise estrogen levels, increasing the risk of endometrial cancer.

- Age: This cancer is more common in postmenopausal women.

- Certain medical conditions: Conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and diabetes can increase the risk.

- Family history: A family history of endometrial cancer or certain genetic conditions, such as Lynch syndrome, can also raise the risk.

How is the diagnosis of endometrial endometrioid carcinoma made?

The diagnosis of endometrial endometrioid carcinoma is made through a biopsy, where a small tissue sample is taken from the endometrium and examined under a microscope by a pathologist. The pathologist looks for abnormal cells and their growth pattern, which helps confirm the diagnosis of endometrial endometrioid carcinoma.

Microscopic features of this tumour

When examined under a microscope, endometrial endometrioid carcinoma displays a variety of growth patterns, reflecting the abnormal way the tumour cells are organized. The tumour typically shows a combination of glandular, papillary, and solid growth:

- Glandular growth: This refers to tumour cells forming gland-like structures, which is similar to how normal endometrial cells are arranged. These glands often appear irregular, with abnormal shapes and sizes.

- Papillary growth: In this pattern, the tumour forms finger-like projections, known as papillae, that extend into the spaces around the tumour. Papillary growth can give the tumour a more complex appearance.

- Solid growth: Solid areas occur when the tumour cells lose their organized glandular structure and form solid sheets or clusters. Solid growth is often associated with more aggressive tumour behaviour, especially when it makes up a large portion of the tumour. The percentage of solid growth is used to determine the FIGO grade.

In addition to these patterns, squamous differentiation is common in endometrial endometrioid carcinoma. This means that some areas of the tumour start to look like squamous cells, which are flat cells that typically line the surface of certain tissues, such as the skin. Squamous differentiation can give parts of the tumour a more solid appearance and is a feature frequently observed in this type of cancer.

FIGO grade

The FIGO grade is a system pathologists uses to assess how much the tumour cells in endometrial endometrioid carcinoma differ from normal endometrial cells. This assessment is done by examining the tumour under a microscope and determining the percentage of non-squamous solid growth (areas where the tumour cells form solid clusters rather than the organized glands seen in healthy tissue).

The FIGO grade is important because it helps guide treatment decisions and provides information about the tumour’s likely behaviour. Higher-grade tumours grow more quickly and have a greater chance of spreading (metastasizing), while lower-grade tumours are generally less aggressive.

The FIGO system divides tumours into two main categories:

- Low grade (FIGO 1 and FIGO 2): Low grade endometrial endometrioid carcinoma includes both FIGO grade 1 (less than 5% solid growth) and FIGO grade 2 (6% to 50% solid growth) tumours. Low grade tumours grow more slowly and are less likely to spread. They generally have a more favourable prognosis.

- High grade (FIGO 3): High grade endometrial endometrioid carcinoma includes all FIGO grade 3 tumours (more than 50% solid growth). High-grade tumours are more likely to spread and recur and are associated with a poorer prognosis than low grade tumours.

Molecular subtypes of endometrial endometrioid carcinoma

Endometrial endometrioid carcinoma can be divided into different molecular subtypes based on specific genetic changes in the tumour cells. Pathologists use special tests to identify these subtypes, and each one has implications for prognosis and treatment.

- POLE-ultramutated endometrioid carcinoma: This subtype is caused by mutations in the POLE gene, which helps repair DNA during cell division. Pathologists use molecular tests such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) to look for mutations in the POLE gene. A positive result confirms the presence of a POLE mutation, and these tumours are generally associated with a favourable prognosis. Patients with POLE-ultramutated tumours have a lower risk of recurrence and respond well to treatment.

- Mismatch repair–deficient endometrioid carcinoma: MMR-deficient tumours arise from defects in the mismatch repair (MMR) system. Pathologists use immunohistochemistry (IHC) to test for the loss of expression of four key MMR proteins: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. A negative result for one or more of these proteins indicates MMR deficiency. These tumours are associated with an intermediate prognosis and may require testing for Lynch syndrome, a genetic condition linked to an increased cancer risk.

- p53-mutant endometrioid carcinoma: This subtype involves mutations in the p53 gene. Pathologists also use immunohistochemistry (IHC) to check for abnormal patterns of p53 protein expression. A strongly positive (overexpression) or completely absent (null) result typically indicates a p53 mutation. Tumours with p53 mutations are more aggressive and are linked to a poorer prognosis, often requiring more intensive treatment.

- No specific molecular profile (NSMP) endometrioid carcinoma: Tumours in this subtype show none of the genetic changes seen in the other subtypes. Pathologists identify NSMP tumours by a process of exclusion, where genetic testing and immunohistochemistry (IHC) do not reveal any mutations or deficiencies in the POLE, MMR, or p53 pathways. NSMP tumours have an intermediate prognosis, and their behaviour tends to fall between the more favourable POLE-ultramutated and the more aggressive p53-mutant subtypes.

These molecular subtypes help guide treatment plans and provide valuable information about how the cancer may behave. The tests used to identify these subtypes are key tools for personalizing patient care.

Myometrial invasion

The myometrium is the thick muscular layer of the uterus. Myometrial invasion occurs when the cancer spreads from the inner lining of the uterus (the endometrium) into the myometrium. The depth of myometrial invasion is important because the more deeply the tumour invades, the higher the risk of spreading to other body parts.

Most pathology reports for endometrial endometrioid carcinoma will describe the amount of myometrial invasion in millimetres and as a percentage of the total myometrial thickness. This information is used to stage the tumour and to plan treatment.

Cervical stromal invasion

Cervical stromal invasion means that the cancer has spread from the body of the uterus into the cervix, which is the lower part of the uterus that connects to the vagina. This type of invasion indicates a more advanced stage of cancer and may influence treatment decisions, such as the need for more extensive surgery or radiation therapy.

Invasion of surrounding organs or tissues

The uterus is closely connected to several other organs and tissues, such as the ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina, bladder, and rectum. The term “adnexa” refers to the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and ligaments directly linked to the uterus. As a tumour grows, it can spread into any of these organs or tissues. In such cases, some parts of these organs or tissues may have to be removed along with the uterus. A pathologist will thoroughly examine these organs or tissues for tumour cells, and the findings will be detailed in your pathology report. The presence of tumour cells in other organs or tissues is significant, as it raises the pathologic tumour stage and is linked with a poorer prognosis.

Lymphatic and vascular invasion

Lymphatic invasion occurs when cancer cells enter the lymphatic system, a network of vessels that helps fight infection. Vascular invasion refers to cancer cells entering the blood vessels. Both lymphatic and vascular invasion are important because they can indicate that the cancer is more likely to spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body, including lymph nodes and distant organs. These findings are often included in a pathology report to help guide treatment decisions.

Margins

A margin refers to the edge of the tissue that is removed during surgery, such as a hysterectomy. After the surgery, pathologists examine the margins of the tissue under a microscope to check for any remaining cancer cells. In the case of endometrial endometrioid carcinoma, several specific margins are carefully evaluated:

- Cervical margin: This is the edge where the uterus meets the cervix. Pathologists examine this margin to see if the cancer has spread into or beyond the cervix.

- Vaginal cuff margin: If the top portion of the vagina is removed along with the uterus, the pathologist will check the vaginal cuff margin to ensure no cancer cells are present at the surgical edge.

- Parametrial margin: This margin includes the tissue around the uterus, including ligaments and connective tissue. It is examined to see if cancer has spread into these areas.

- Peritoneal margin: If the peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity) is removed, it will be examined to check for cancer cells in this area.

If any of these margins contain cancer cells, it is referred to as a positive margin, which may mean that some tumour cells were left behind after surgery. A negative margin means no cancer cells were found at the edges, suggesting that the tumour was completely removed. Clear margins are important for reducing the risk of the cancer returning, and positive margins may lead to recommendations for additional treatments, such as radiation therapy.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped structures that are part of the lymphatic system, which helps fight infection and remove waste from the body. Lymph nodes contain immune cells that filter lymph fluid, which travels through lymphatic vessels, and help trap harmful substances like bacteria or cancer cells. Lymph nodes are located throughout the body, including in the pelvis and abdomen, close to the uterus.

In the context of endometrial endometrioid carcinoma, lymph nodes are examined because this type of cancer has a higher risk of spreading beyond the uterus, particularly to nearby lymph nodes. For this reason, your surgeon may remove lymph nodes from the pelvis or abdomen, which are then sent to the pathologist for examination under a microscope. This is done to check for the presence of metastatic cancer (cancer that has spread from the primary tumour to other areas of the body).

Examining lymph nodes is important for several reasons:

- Determining the stage of cancer: If cancer cells are found in the lymph nodes, it indicates that the cancer has spread beyond the uterus, which may place the cancer in a more advanced stage.

- Guiding treatment decisions: The presence of cancer in the lymph nodes can affect treatment options. Patients with lymph node involvement may require more aggressive treatments, such as radiation therapy or chemotherapy, to reduce the risk of recurrence.

- Assessing prognosis: Lymph node involvement is associated with a higher risk of the cancer returning or spreading to other parts of the body. Knowing whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes helps doctors provide more accurate information about the patient’s prognosis.

Isolated tumour cells (ITCs)

Pathologists use the term ‘isolated tumour cells’ to describe a group of tumour cells that measures 0.2 mm or less and is found in a lymph node. If only isolated tumour cells are found in all the lymph nodes examined, the pathologic nodal stage is pN1mi.

Micrometastasis

A ‘micrometastasis’ is a group of tumour cells measuring from 0.2 mm to 2 mm that is found in a lymph node. If only micrometastases are found in all the lymph nodes examined, the pathologic nodal stage is pN1mi.

Macrometastasis

A ‘macrometastasis’ is a group of tumour cells measuring more than 2 mm and found in a lymph node. Macrometastases are associated with a worse prognosis and may require additional treatment.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

The pathologic stage for endometrial endometrioid carcinoma is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT) for endometrial endometrioid carcinoma

Endometrial endometrioid carcinoma is given a tumour stage between T1 and T4 based on the depth of myometrial invasion and growth of the tumour outside of the uterus.

- T1 – The tumour only involves the uterus.

- T2 – The tumour has grown to involve the cervical stroma.

- T3 – The tumour has grown through the wall of the uterus and is now on the outer surface of the uterus, OR it has grown to involve the fallopian tubes or ovaries.

- T4 – The tumour has grown directly into the bladder or the colon.

Nodal stage (pN) for endometrial endometrioid carcinoma

Based on the examination of lymph nodes from the pelvis and abdomen, uterine carcinosarcoma is given a nodal stage from N0 to N2.

- N0 – No tumour cells were found in any lymph nodes examined.

- N1mi – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node from the pelvis, but the area with cancer cells was not larger than 2 millimetres (only isolated cancer cells or micrometastasis).

- N1a – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node from the pelvis, and the area with cancer cells was greater than 2 millimetres (macrometastasis).

- N2mi – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node outside the pelvis, but the area with cancer cells was not larger than 2 millimetres (only isolated cancer cells or micrometastasis).

- N2a – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node outside the pelvis, and the area with cancer cells was greater than 2 millimetres (macrometastasis).

- NX – No lymph nodes were sent for examination.

FIGO stage

The FIGO staging system, developed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, is a standardized way of classifying endometrial cancers based on how far they have spread. This system is important because it helps doctors determine the extent of the cancer, plan appropriate treatment, and estimate the prognosis (the likely disease outcome).

- Stage I: The cancer is confined to the uterus.

- IA: The cancer is limited to the endometrium or has invaded less than halfway into the myometrium.

Prognosis: Cancers in Stage IA have an excellent prognosis, with a high likelihood of being successfully treated through surgery alone. - IB: The cancer has invaded more than halfway into the myometrium.

Prognosis: Although Stage IB is more advanced than Stage IA, it generally has a good prognosis, especially if treated promptly.

- IA: The cancer is limited to the endometrium or has invaded less than halfway into the myometrium.

- Stage II: The cancer has spread from the uterus to the cervix but has not gone beyond the uterus.

Prognosis: Stage II cancers are more likely to require additional treatments, such as radiation or chemotherapy, but many patients still have a favourable outcome with appropriate treatment. - Stage III: The cancer has spread beyond the uterus but is still within the pelvis.

- IIIA: The cancer has spread to the outer surface of the uterus or to nearby tissues.

- IIIB: The cancer has spread to the vagina or the pelvic wall.

- IIIC: The cancer has spread to lymph nodes.

Prognosis: Stage III cancers are more advanced and often require a combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. The prognosis is more guarded, but treatment can still be effective in many cases.

- Stage IV: The cancer has spread to distant organs, such as the bladder, bowel, or lungs.

- IVA: The cancer has spread to nearby organs such as the bladder or rectum.

- IVB: The cancer has spread to distant organs, such as the lungs or liver.

Prognosis: Stage IV cancers are the most advanced and carry a more serious prognosis. Treatment at this stage is usually focused on managing symptoms and slowing the progression of the disease.