by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

July 17, 2024

Background:

Mucosal melanoma is a type of cancer made up of abnormal melanocytes. In the head and neck, the tumour starts from a thin layer of tissue called mucosa, which covers the inside of the mouth (oral cavity), nose (nasal cavity), paranasal sinuses (maxillary sinus, ethmoid sinus, frontal sinus, and sphenoid sinus), and throat (pharynx and larynx).

What are the symptoms of mucosal melanoma?

The symptoms of mucosal melanoma vary depending on the area of the head and neck involved. Tumours that start in the nose (nasal cavity) or one of the paranasal sinuses can cause symptoms such as nasal congestion, runny nose, or frequent nose bleeds. Tumours that start in the mouth (oral cavity) frequently do not cause any symptoms, although some patients may experience pain later in the disease. Tumours that start in the throat can cause voice changes such as hoarseness or difficulty breathing.

What causes mucosal melanoma?

Doctors do not know what causes most mucosal melanomas. However, people with a non-cancerous condition called mucosal melanosis appear to be at a higher risk of developing this type of cancer at some point in their lives. Unlike melanoma in the skin, mucosal melanoma in the head and neck is not caused by excessive exposure to UV light (such as the sun).

How common is mucosal melanoma?

Mucosal melanoma in the head and neck is a very rare disease that accounts for approximately 1% of all cases of melanoma. Most melanomas start in the skin.

How is the diagnosis of mucosal melanoma made?

The diagnosis is usually made after a small sample of the tumour is removed in a procedure called a biopsy. The tissue is then sent to a pathologist, who examines it under a microscope. A second surgical procedure is then usually performed to remove the entire tumour.

Your pathology report for mucosal melanoma of the head and neck:

Microscopic features of mucosal melanoma

Mucosal melanoma is made up of abnormal melanocytes. Melanocytes are a specialized type of cell that can be found throughout the body. Melanocytes make a brown pigment called melanin and this pigment may be seen in the tumour. The cancer cells in the tumour may be described as epithelioid (round), spindled (long and thin), rhabdoid (similar to muscle cells), plasmacytoid (similar to immune cells called plasma cells), or clear (the cytoplasm, or body of the cell, looks clear). A type of cell death called necrosis and mitotic figures (cancer cells dividing to create new cancer cells) are also typically seen.

What other tests may be performed to confirm the diagnosis of mucosal melanoma?

Your pathologist may perform a test called immunohistochemistry to confirm the diagnosis. This test allows your pathologist to see specialized chemicals called proteins inside the cancer cells. The cancer cells in the tumour make the same proteins found in normal melanocytes. These proteins include S100, SOX-10, Melan-A, and HMB-45.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, unlike lymphatic vessels, which carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic vessels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it spreads cancer cells to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the liver, via the blood or lymphatic vessels.

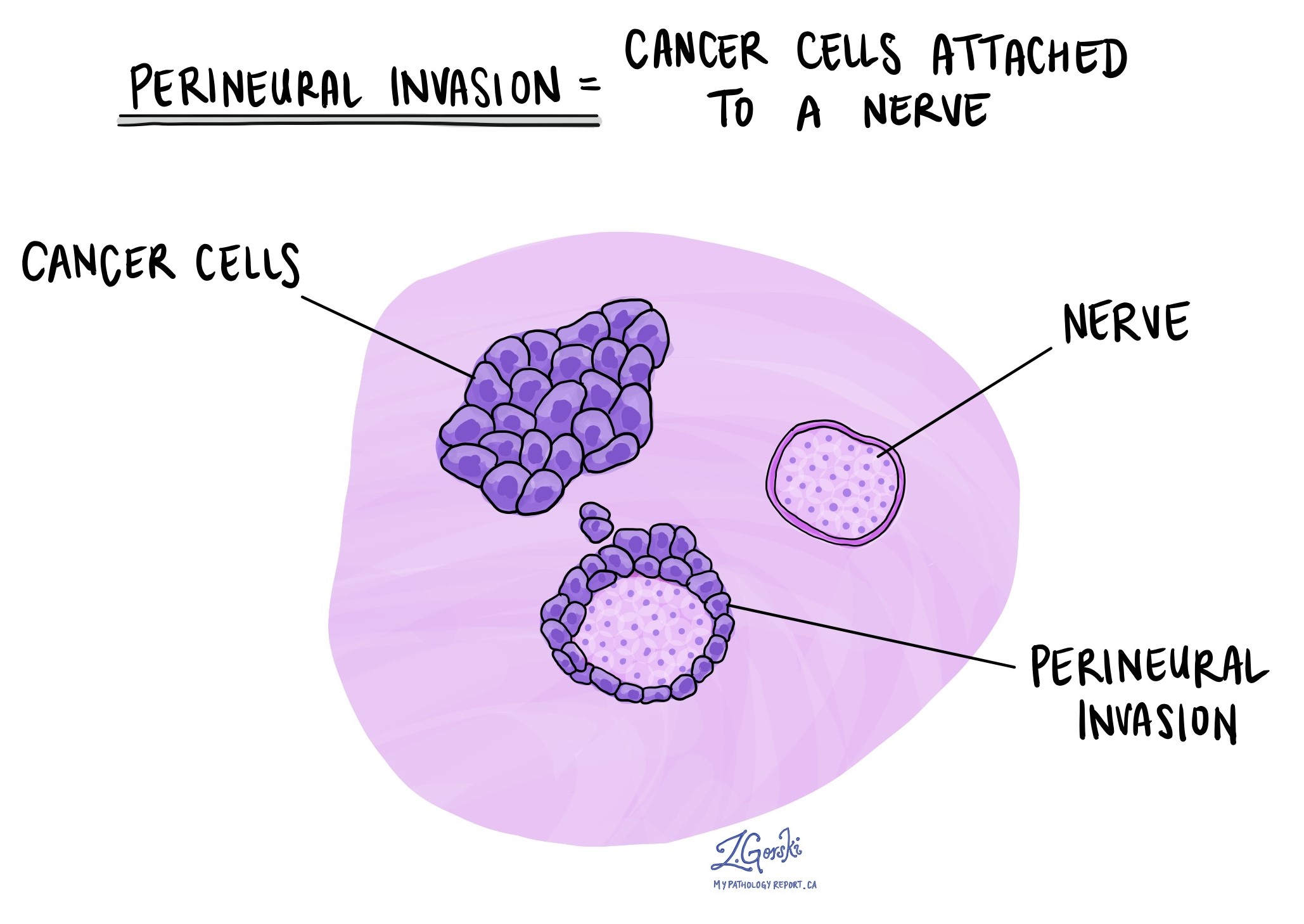

Perineural invasion

Pathologists use the term “perineural invasion” to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that specifically refers to cancer cells found inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. The presence of perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure, like an excision or resection, that removes the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are present at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was fully removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

Lymph nodes

Small immune organs, known as lymph nodes, are located throughout the body. Cancer cells can travel from a tumour to these lymph nodes via tiny lymphatic vessels. For this reason, doctors often remove and microscopically examine lymph nodes to look for cancer cells. This process, where cancer cells move from the original tumour to another body part, like a lymph node, is termed metastasis.

Cancer cells usually first migrate to lymph nodes near the tumour, although distant lymph nodes may also be affected. Consequently, surgeons typically remove lymph nodes closest to the tumour first. They might remove lymph nodes farther from the tumour if they are enlarged and there’s a strong suspicion they contain cancer cells.

Pathologists will examine any lymph nodes that have been removed under a microscope, and the findings will be detailed in your report. A “positive” result indicates the presence of cancer cells in the lymph node, while a “negative” result means no cancer cells were found. If the report finds cancer cells in a lymph node, it might also specify the size of the largest cluster of these cells, often referred to as a “focus” or “deposit.” Extranodal extension occurs when tumour cells penetrate the lymph node’s outer capsule and spread into the adjacent tissue.

Examining lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, it helps determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, discovering cancer cells in a lymph node suggests an increased risk of later finding cancer cells in other body parts. This information guides your doctor in deciding whether you need additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

Your pathologist can only determine the tumour stage after the entire tumour has been removed. By definition, all mucosal melanomas of the head and neck are given a tumour stage (pT) of pT3 or pT4. A tumour is considered pT3 when it only involves the mucosa in one area of the head and neck. A tumour that grows into surrounding tissues, including bones, large nerves, blood vessels, or the skin, is considered pT4. The nodal stage (pN) is based on examining lymph nodes to look for cancer cells. If no cancer cells are found in any of the lymph nodes examined, the nodal stage is pN0. If cancer cells are found in any of the lymph nodes examined, the nodal stage is pN1. In cases where no lymph nodes were sent for examination by the pathologist, the nodal stage cannot be determined as is called pNx. Higher-stage tumours (those that are pT4 or pN1) are associated with a worse prognosis.

About this article

This article was written by doctors to help you read and understand your pathology report. Contact us with any questions about this article or your pathology report. Read this article for a more general introduction to the parts of a typical pathology report.