by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

December 4, 2024

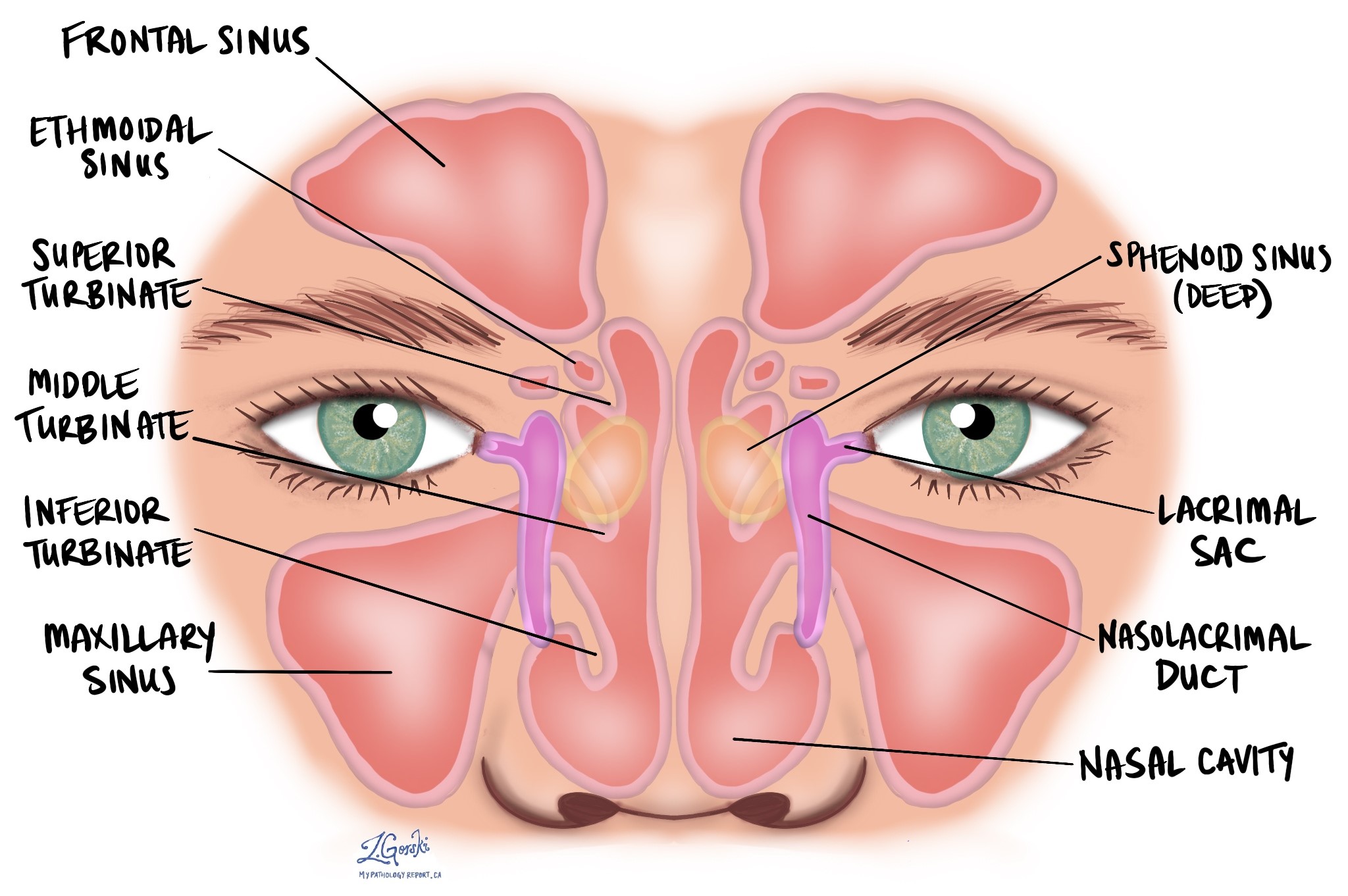

Nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (NKSCC) is a type of cancer that begins from squamous cells, specialized cells found on the inside surface of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. The nasal cavity is the hollow space inside the nose that helps warm, moisten, and filter the air we breathe. The paranasal sinuses, which include the maxillary, frontal, sphenoid, and ethmoid sinuses, are air-filled spaces in the bones around the nose that lighten the weight of the skull and produce mucus to keep the nasal passages moist.

Nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma can develop for various reasons, including infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV), but not all cases are linked to the virus.

What are the symptoms of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma?

Symptoms of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma can depend on the size and location of the tumour but may include:

- Nasal congestion or obstruction.

- Nosebleeds.

- Pain or pressure in the face or around the sinuses.

- Difficulty breathing through the nose.

- A lump or swelling in the nasal area.

- Decreased sense of smell.

Sometimes, the tumour may not cause noticeable symptoms until it grows larger or spreads to nearby structures.

What causes nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma?

Nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma can develop due to several causes:

- Human papillomavirus (HPV): High-risk HPV is implicated in a significant number of cases, especially in North America and Europe, where 36–58% of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinomas are HPV-associated. HPV16, a common high-risk type, is responsible for 41–82% of these cases.

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV): Although rare, some tumours have been linked to EBV, a virus that can cause certain cancers, particularly in the nasal cavity and sinuses.

- Genetic alterations: Genetic changes may drive cancer development in tumours not associated with HPV or EBV. Nearly half of HPV-negative cases show a fusion between two genes, DEK and AFF2, which is thought to promote tumour growth.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma is typically made after a biopsy, where a small sample of tissue is taken from the tumour. A pathologist examines the tissue under a microscope to identify features of cancer. Additional tests may be performed to determine if the tumour is associated with HPV or other underlying causes.

Microscopic features of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma

Under the microscope, nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma is made up of nests, lobules, or ribbons of tumour cells. Unlike squamous cell carcinomas in other parts of the body, nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma does not always invade the surrounding tissue in the traditional sense but can still form a visible mass. These groups of cells often grow in a way that appears to “push” into the surrounding tissue, creating a smooth border with minimal desmoplastic response, even when the tumour invades deeply and destructively. Some tumours show a papillary architecture, forming finger-like projections that can extend along the surface and over nearby normal tissue.

The tumour cells typically have a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, meaning their nuclei are large compared to the rest of the cell. The outer layer of the tumour nests often contains columnar cells arranged in a palisading pattern, with the cells becoming flatter in the center. These tumours lack the keratinization commonly seen in other squamous cell carcinomas.

The degree of atypia, or how abnormal the cells look, can vary widely. In some cases, the cells appear only slightly abnormal, while the changes are more pronounced in others. The number of mitotic figures (dividing cells) and areas of necrosis (dead tumour tissue) can also vary.

Specific subtypes of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma

- HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma: This subtype is linked to high-risk HPV and often shows the classic features of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Most HPV-associated tumours share these characteristics, but some may have unique appearances, such as keratinizing (producing keratin), basaloid (small, dark cells), or adenosquamous (a mix of squamous and gland-like cells) types.

- DEK::AFF2 squamous cell carcinoma: This recently identified subtype is caused by a specific genetic change involving the DEK and AFF2 genes. These tumours often have a distinct growth pattern, forming exophytic (outward) and endophytic (inward) growth structures. They may feature papillary fronds (finger-like projections) and interconnected lobules lined by transitional epithelium, a layer of cells with pinkish or light purple (amphophilic to eosinophilic) cytoplasm. The tumour cells have round to oval nuclei that look uniform and may show areas of discohesion, where the cells are less tightly connected. Immune cells like neutrophils or lymphocytes are often found within the tumour. This subtype shares similarities with a tumour previously known as low-grade papillary sinonasal carcinoma, and research shows that many of these tumours also have the DEK::AFF2 genetic fusion.

What other tests may be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

In addition to examining the tumour under a microscope, several tests may be used to confirm the diagnosis of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma and identify its specific subtype:

- Immunohistochemistry: This test uses special stains to detect proteins in the tumour cells. For tumours suspected to be HPV-associated, the protein p16 is often tested. High levels of p16 suggest that HPV may be involved in the tumour’s development.

- In situ hybridization: This test looks for the DNA or RNA of high-risk HPV within the tumour cells. It is highly specific and helps confirm that HPV is present and active in the tumour.

- Next-generation sequencing (NGS): This advanced test analyzes the genetic material of the tumour cells to detect specific mutations or gene fusions. For nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, NGS can identify the presence of DEK::AFF2 gene fusions, characteristic of a specific subtype of this tumour.

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH): This test uses fluorescent probes to detect specific genetic changes in the tumour cells. FISH targeting the DEK gene can confirm the presence of DEK::AFF2 gene fusions.

These additional tests help to identify the tumour’s molecular and genetic characteristics, which can provide more precise information about its cause and guide treatment decisions.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, unlike lymphatic vessels, which carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic vessels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it spreads cancer cells to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the liver, via the blood or lymphatic vessels.

Perineural invasion

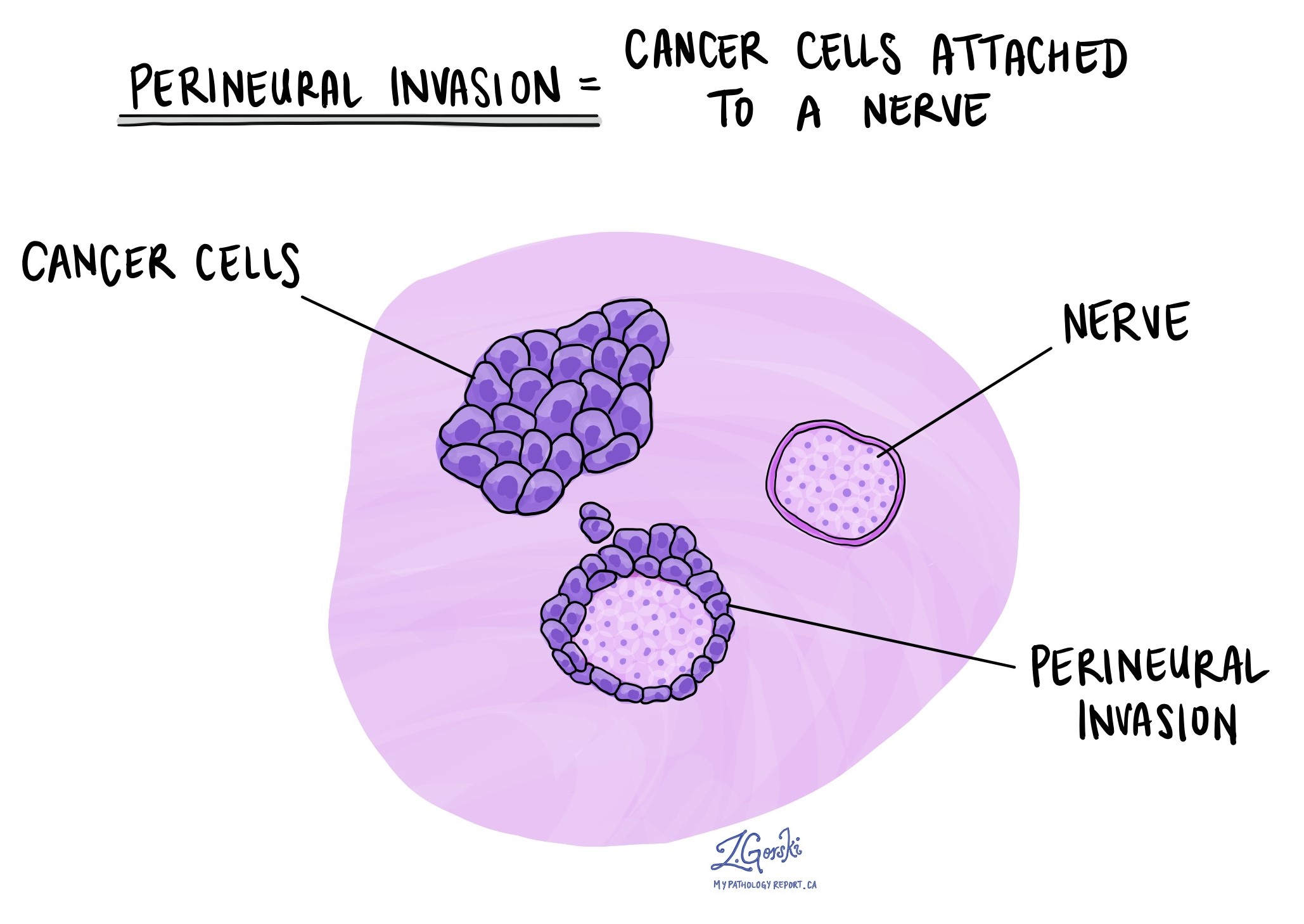

Pathologists use the term “perineural invasion” to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that specifically refers to cancer cells inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. Perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure, like an excision or resection, that removes the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was entirely removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

Lymph nodes

Small immune organs, known as lymph nodes, are located throughout the body. Cancer cells can travel from a tumour to these lymph nodes via tiny lymphatic vessels. For this reason, doctors often remove and microscopically examine lymph nodes to look for cancer cells. This process, where cancer cells move from the original tumour to another body part, like a lymph node, is termed metastasis.

Cancer cells usually first migrate to lymph nodes near the tumour, although distant lymph nodes may also be affected. Consequently, surgeons typically remove lymph nodes closest to the tumour first. They might remove lymph nodes farther from the tumour if they are enlarged and there’s a strong suspicion they contain cancer cells.

Pathologists will examine any lymph nodes removed under a microscope, and the findings will be detailed in your report. A “positive” result indicates the presence of cancer cells in the lymph node, while a “negative” result means no cancer cells were found. If the report finds cancer cells in a lymph node, it might also specify the size of the largest cluster of these cells, often referred to as a “focus” or “deposit.” Extranodal extension occurs when tumour cells penetrate the lymph node’s outer capsule and spread into the adjacent tissue.

Examining lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, it helps determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, discovering cancer cells in a lymph node suggests an increased risk of later finding cancer cells in other body parts. This information guides your doctor in deciding whether you need additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy.

Pathologic staging of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma

Staging describes the amount and location of cancer in the body. For nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, the staging system helps determine the size and extent of the tumour (T stage) and whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes (N stage). This information guides treatment and helps predict outcomes.

The tumour stage (T stage) depends on where the tumour started—whether in the maxillary sinus, nasal cavity, or ethmoid sinus—as different structures and patterns of spread are associated with each location. Each site has its own staging criteria, reflecting the unique anatomy of these regions.

T stages (tumour stages)

Maxillary sinus

- Tis: The cancer is “in situ,” meaning it is confined to the surface layer and has not invaded deeper tissues.

- T1: The tumour is limited to the lining (mucosa) of the maxillary sinus and has not caused bone damage.

- T2: The tumour has caused bone damage or extends to nearby areas, such as the hard palate or middle nasal passage, but not the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus or pterygoid plates.

- T3: The tumour invades deeper areas, such as the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, soft tissues, floor or medial wall of the eye socket (orbit), pterygoid fossa, or ethmoid sinuses.

- T4: Advanced disease, divided into:

- T4a: Moderately advanced, involving areas like the front part of the eye socket, cheek skin, or other nearby bones (cribriform plate, frontal or sphenoid sinuses).

- T4b: Very advanced, involving critical areas like the brain, cranial nerves, or skull base.

Nasal cavity and ethmoid sinus

- Tis: Cancer is “in situ,” confined to the surface layer.

- T1: The tumour is limited to one area of the nasal cavity or ethmoid sinus, with or without bone involvement.

- T2: The tumour affects two regions within the nasal cavity or ethmoid sinus or extends to adjacent areas, with or without bone involvement.

- T3: The tumour invades critical structures like the floor or medial wall of the orbit, maxillary sinus, palate, or cribriform plate.

- T4: Advanced disease, divided into:

- T4a: Moderately advanced, involving the front of the eye socket, cheek skin, minimal extension into the skull base, or nearby bones.

- T4b: Very advanced, involving the brain, cranial nerves, or deep areas of the skull.

N stages (lymph node stages)

- N0: No cancer is found in nearby lymph nodes.

- N1: Cancer is present in one lymph node on the same side of the neck, and the node is 3 cm or smaller in size without signs of spread outside the node (ENE-negative).

- N2: Cancer has spread to one or more lymph nodes, but none larger than 6 cm. It is divided into:

- N2a: A single lymph node, either 3 cm or smaller with signs of spread outside the node (ENE-positive), or larger than 3 cm but not larger than 6 cm without spread outside the node.

- N2b: Cancer in multiple lymph nodes on the same side of the neck, none larger than 6 cm, and ENE-negative.

- N2c: Cancer in lymph nodes on both sides of the neck or opposite the tumour, none larger than 6 cm, and ENE-negative.

- N3: More advanced lymph node involvement, including:

- N3a: A lymph node larger than 6 cm without spread outside the node.

- N3b: Any lymph node with spread outside the node (ENE-positive), or multiple affected lymph nodes with ENE.

Prognosis

The prognosis for nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma depends on several factors, including the size of the tumour, its location, whether it has spread to nearby tissues or distant organs, and the person’s overall health. The five-year survival rate for sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma is approximately 60%. Some studies suggest that tumours associated with HPV may have a better prognosis compared to those not linked to HPV, but this benefit is not consistently observed in clinical practice. Tumours with features such as deep invasion or necrosis may be associated with worse outcomes.