by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

February 28, 2025

NUT carcinoma is a rare and aggressive type of cancer that can develop in different parts of the body, most commonly in the head, neck, or chest. It grows quickly and spreads quickly, making early diagnosis and treatment important. NUT carcinoma is named after a specific genetic change that affects the NUTM1 gene, which plays a role in cell growth.

What are the symptoms of NUT carcinoma?

The symptoms of NUT carcinoma depend on where the tumour is located. In the head and neck, it may cause swelling, difficulty swallowing, voice changes, or breathing problems. In the chest, symptoms may include cough, chest pain, or shortness of breath. Some people experience weight loss, fatigue, or pain if the cancer has spread to other areas of the body.

What causes NUT carcinoma?

NUT carcinoma is caused by a mutation (genetic change) that leads to uncontrolled cell growth. This mutation occurs when the NUTM1 gene joins with another gene, most often BRD4 or BRD3, creating a fusion gene. This fusion gene prevents cells from maturing normally, leading to the rapid and aggressive growth of cancer cells. The exact reason why this mutation occurs is unknown, and there are no known risk factors or inherited causes.

How is this diagnosis made?

Doctors diagnose NUT carcinoma by examining a tumour biopsy under a microscope. Because this cancer is rare, special tests such as immunohistochemistry and genetic testing (such as FISH or next-generation sequencing) are often used to confirm the presence of the NUTM1 gene fusion.

Microscopic features of this tumour

When examined under a microscope, NUT carcinoma is made up of small to medium-sized cancer cells that look very similar to each other. These cells have irregularly shaped nuclei, which contain the genetic material of the cell, and prominent nucleoli, which are small structures inside the nucleus. The cancer cells are arranged in sheets or nests, and there is often a lot of mitotic activity (cell division) and necrosis (dead cells). One of the most distinctive features of NUT carcinoma is areas where the cells suddenly start producing keratin, a protein normally found in skin and hair. Pathologists describe this as “abrupt keratinization”. However, this feature is only seen in about one-third of cases. The tumour is often surrounded by inflammatory cells, particularly neutrophils, which are a type of immune cell. Unlike other cancers, NUT carcinoma does not typically show glandular (gland-forming) or mesenchymal (connective tissue-like) features.

Do pathologists grade NUT carcinoma?

No, pathologists do not assign a grade to NUT carcinoma like they do for some other cancers. This is because NUT carcinoma is always considered high grade, meaning it is an aggressive cancer that grows and spreads quickly.

What other tests may be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

Pathologists use a test called immunohistochemistry to detect specific proteins in the cancer cells. In most cases, NUT carcinoma shows strong staining for the NUT protein, which confirms the diagnosis. The staining pattern is often punctate, appearing in small dots inside the cells. Other tests may show that the cancer cells produce pancytokeratin, a protein found in many types of carcinoma, and p63/p40, which suggests squamous differentiation. In some cases, the tumour may also stain for chromogranin, synaptophysin, or TTF1, proteins seen in other cancers, making diagnosis more challenging. CD34, a protein typically found in blood-forming cells, may also be present, which can lead to confusion with leukemia. A test called Ki-67 is often very high in NUT carcinoma, indicating that the cells are growing rapidly.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells have entered small blood vessels or lymphatic channels. This is important because it increases the risk of the cancer cells spreading (metastasising) to other body parts. If lymphovascular invasion is seen in a pathology report, doctors may recommend additional treatments to help reduce the risk of the cancer returning.

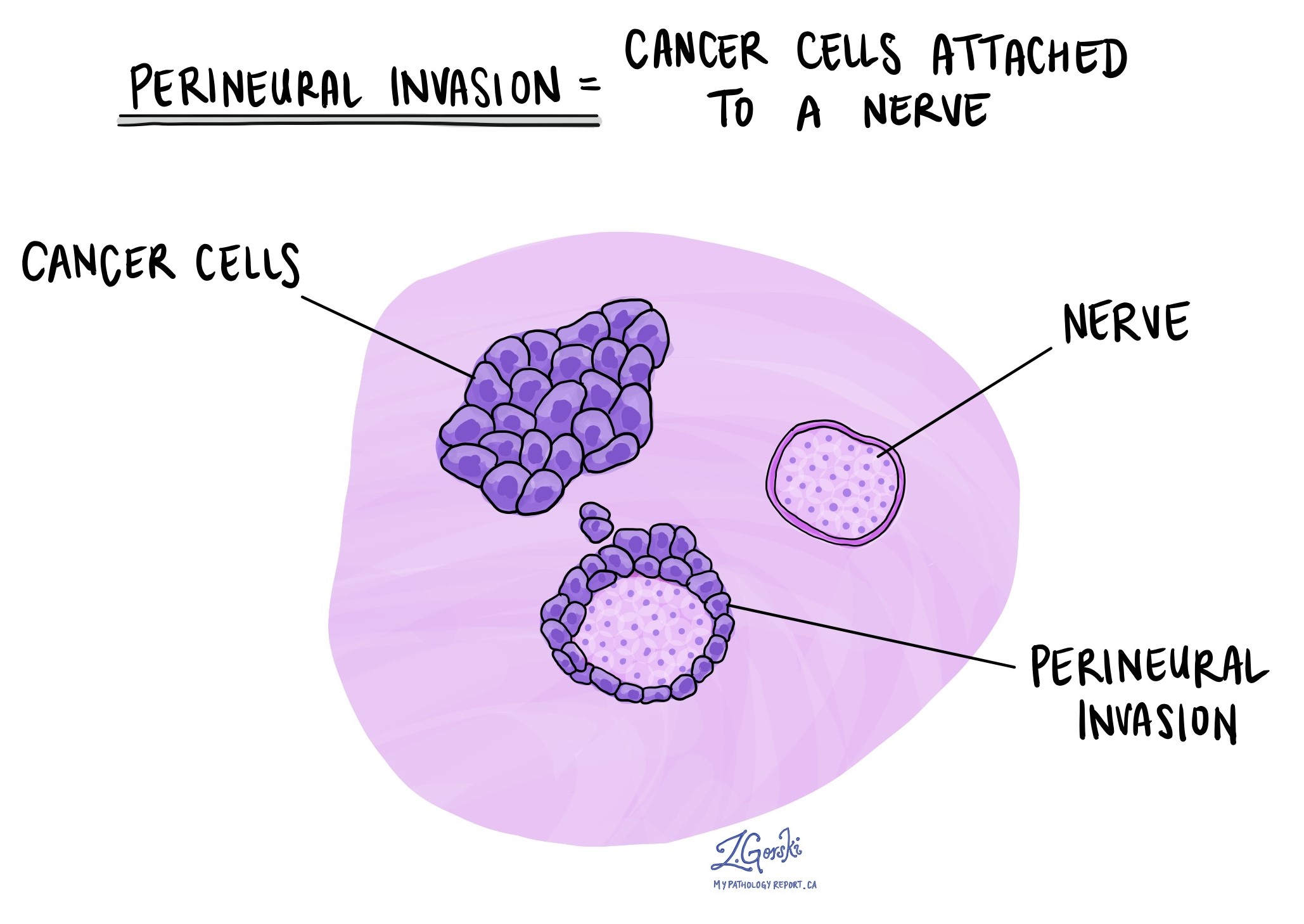

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion occurs when cancer cells spread along nerves. This can cause pain, numbness, or weakness if important nerves are affected. It also suggests that the cancer is more aggressive and may be harder to completely remove with surgery.

Margins

A margin refers to the edge of the tissue removed during surgery. If cancer cells are found at the margin (positive margin), it means that some cancer may still be left in the body, and further treatment may be needed. A negative margin means that no cancer cells were found at the edges of the removed tissue, lowering the chance of the cancer returning.

What is the prognosis for a person diagnosed with NUT carcinoma?

NUT carcinoma is an extremely aggressive cancer, and survival rates are generally very poor. The median survival time (when half of the patients are still alive) is about 6.5 months. However, survival depends on the location of the tumour and the specific genetic changes present. People with NUT carcinoma in the chest (thoracic NUT carcinoma) with a BRD4-NUTM1 fusion have the worst prognosis, with a median survival of about 4.4 months. In contrast, people with NUT carcinoma outside the chest with a non-BRD4 fusion have a better prognosis, with a median survival of about 36.5 months.

Complete surgical removal of the tumour and early treatment with radiation therapy have been linked to better survival. Chemotherapy is often used, but most traditional chemotherapy regimens have not provided long-term responses. However, some studies suggest that ifosfamide-based chemotherapy (such as the Ewing sarcoma Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG) IX protocol) may help a small number of patients, especially in children.

Researchers are currently studying new treatments, including BET inhibitors, which are drugs that specifically target the BRD4 protein involved in NUT carcinoma. Clinical trials are ongoing to determine whether these treatments may improve survival for patients with this rare and aggressive cancer.