by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

January 8, 2025

Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma (PDTC) is a rare type of thyroid cancer that falls between well differentiated thyroid cancers, such as papillary thyroid carcinoma and follicular thyroid carcinoma, and the more aggressive anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. This type of cancer is considered high-grade, meaning it tends to grow and spread more quickly than other thyroid cancers. Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma can develop on its own or arise from less aggressive thyroid cancers that have become more advanced. It is an important diagnosis because it often requires more aggressive treatment and closer follow-up.

What causes poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma?

Current research suggests that a combination of genetic and environmental factors contribute to the development of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma. However, no single factor has been identified that makes a person more likely to develop this tumour.

What are the symptoms of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma?

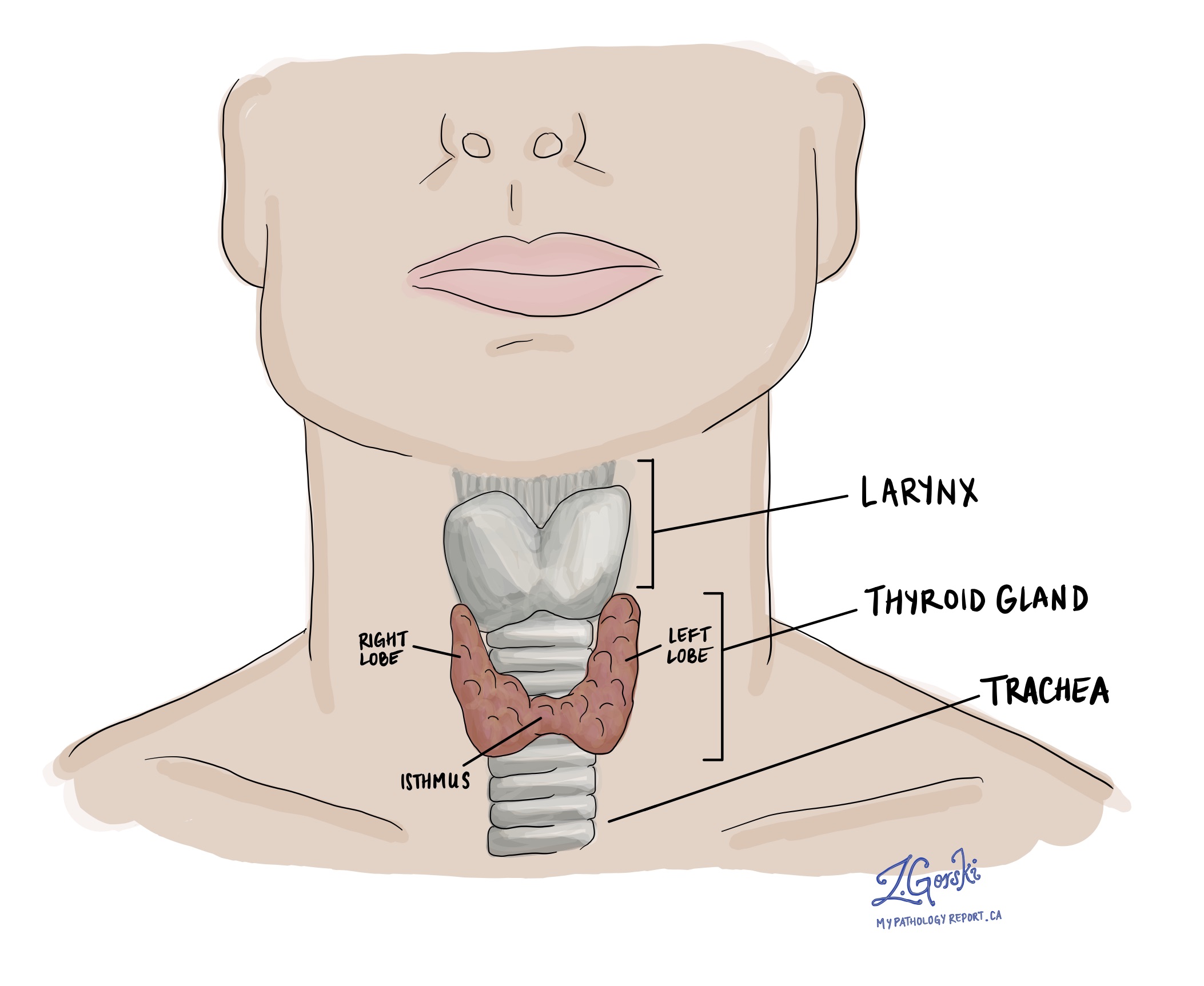

Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma is a fast-growing tumour that starts in the thyroid gland. As a result, people often notice a growth in the front of the neck. As the tumour grows, it can put pressure on surrounding tissues such as the esophagus or trachea, resulting in difficulty breathing or swallowing food. If tumour cells have spread to lymph nodes in this area, a lump may be felt or seen on the side of the neck.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma involves several steps:

- Physical examination: Evaluation of the neck for lumps or nodules.

- Ultrasound: Imaging to assess the thyroid and surrounding structures, providing details about the nodule’s size, composition, and vascularity.

- Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy: A sample of cells is taken from the nodule and examined under a microscope. However, FNA cannot definitively distinguish between benign and malignant follicular tumours.

- Thyroid function tests: Blood tests to measure levels of thyroid hormones and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

- Surgical removal of the nodule: Surgery is often required to diagnose papillary thyroid carcinoma. This usually involves removing half of the thyroid gland. The nodule is then sent to a pathologist for histopathological examination.

Microscopic features of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma

Under the microscope, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma has unique features that pathologists use to make the diagnosis. These features are based on internationally accepted criteria known as the Turin consensus.

To diagnose poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma, pathologists look for:

- Growth pattern: The cancer cells often form solid sheets, small clusters, or structures called trabeculae (thin, elongated arrangements of cells). Another typical pattern involves tight groups of cells called “insulae.” These nests of cells are surrounded by thin connective tissue and may appear separated by small gaps.

- Nuclear characteristics: The cells typically have small, round nuclei with dark, condensed chromatin. They lack the distinctive nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma, such as clear centers or inclusions. In some cases, the nuclei may have irregular shapes, resembling raisins, but they appear darker than those in papillary carcinoma.

- High-grade features:

- Increased cell division: Pathologists look for mitotic figures (dividing cells) and count the number of these cells in a specified tissue area.

- Tumour necrosis: Necrosis (dead tumour cells) may be seen in the centre of cell clusters or as larger areas of dead tissue.

- Other cellular types: Some poorly differentiated thyroid carcinomas contain unique cell types, including cells that appear oncocytic (containing an abnormally high number of mitochondria), clear, mucinous, or signet-ring shaped. These variations are uncommon but may be present.

- Minimal colloid: Unlike well differentiated thyroid cancers, which often produce colloid (a protein-rich substance found in thyroid follicles), poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma shows very little colloid formation.

- Mixed features: Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma may coexist with other types of thyroid cancer in the same tumour. For example, areas of follicular thyroid carcinoma or papillary thyroid carcinoma may be present. Sometimes, parts of the tumour may show progression to anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, which is even more aggressive.

Tumour size

After the tumour is removed completely, it will be measured. The tumour is usually measured in three dimensions, but only the largest dimension is described in your report. For example, if the tumour measures 4.0 cm by 2.0 cm by 1.5 cm, your report will describe it as 4.0 cm. Tumour size is important for follicular thyroid carcinoma because it determines the pathologic tumour stage (pT). Larger tumours are more likely to spread to other body parts, such as lymph nodes.

Extrathyroidal extension

Extrathyroidal extension (ETE) refers to the spread of cancer cells beyond the thyroid gland into surrounding tissues. It is an important prognostic factor in thyroid cancer, as it can significantly influence the disease’s staging and management.

Extrathyroidal extension is classified into two types based on the extent of the spread:

- Microscopic extrathyroidal extension: This is only visible under a microscope and indicates that the cancer has spread just beyond the thyroid capsule. It cannot be seen with the naked eye and may involve minimal infiltration into surrounding soft tissues.

- Macroscopic (or gross) extrathyroidal extension: This type is visible to the naked eye or detectable during surgery. It involves more obvious and extensive invasion into neighbouring structures such as muscles, trachea, esophagus, or major blood vessels.

Extrathyroidal extension is important for the following reasons:

- Prognosis: Macroscopic (gross) extrathyroidal extension is associated with a worse prognosis. It suggests a more aggressive cancer that is more likely to recur and metastasize.

- Staging: Extrathyroidal extension impacts the staging of thyroid cancer. For instance, in the TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) classification system used for thyroid cancer, macroscopic extrathyroidal extension results in a higher pathologic tumour stage (pT).

- Treatment and follow-up: The presence of macroscopic (gross) extrathyroidal extension might lead to more aggressive treatment strategies and closer follow-up to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Vascular invasion (angioinvasion)

In poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma, vascular invasion (also known as angioinvasion) means the cancer cells have spread into the blood vessels in or around the tumour. This is an important sign because it can indicate that the cancer might spread to other body parts, such as the lungs or bones.

Pathologists use two terms to describe how much vascular invasion (angioinvasion) is present:

- Focal vascular invasion (angioinvasion): Cancer cells are found in less than four blood vessels.

- Extensive vascular invasion (angioinvasion): Cancer cells are found in four or more blood vessels.

Extensive vascular invasion (four or more blood vessels) usually means a higher risk of the cancer spreading, which can lead to a worse prognosis. If there is extensive angioinvasion, doctors often recommend more aggressive treatments to try to control the cancer better. This could include additional surgery, radioactive iodine therapy, or more frequent follow-up visits to monitor for any signs of cancer spreading.

Lymphatic invasion

Lymphatic invasion in the context of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma of the thyroid gland refers to the infiltration and spread of cancer cells into the lymphatic system. Cancer cells that enter the lymphatic system can travel to lymph nodes. It is relatively uncommon to find lymphatic invasion with follicular thyroid carcinoma. Unlike vascular invasion, lymphatic invasion is not necessarily associated with a more aggressive disease or a worse prognosis.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests that the tumour was entirely removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread through lymphatic vessels from a tumour to lymph nodes. For this reason, lymph nodes are commonly removed and examined under a microscope to look for cancer cells. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to another part of the body, such as a lymph node, is called metastasis.

Cancer cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour, although lymph nodes far away can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are typically removed only if they are enlarged, and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancer cells in them.

Neck dissections

A neck dissection is a surgical procedure to remove lymph nodes from the neck. The lymph nodes removed usually come from different neck areas, and each region is called a level. The levels in the neck include 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Your pathology report will often describe how many lymph nodes were seen in each level sent for examination. Lymph nodes on the same side as the tumour are called ipsilateral, while those on the opposite side of the tumour are called contralateral.

How the lymph nodes will be described in your pathology report

If any lymph nodes are removed from your body, they will be examined under the microscope by a pathologist, and the examination results will be described in your report. “Positive” means that cancer cells were found in the lymph node. “Negative” indicates that no cancer cells were found. If cancer cells are found in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) may also be included in your report. Extranodal extension means that the tumour cells have broken through the capsule outside of the lymph node and spread into the surrounding tissue.

Why is the examination of lymph nodes important?

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information determines the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment, such as radioactive iodine, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy, is required.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

The pathologic stage for poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma can only be determined after the entire tumour has been surgically removed and examined under the microscope by a pathologist. The stage is divided into three parts: tumour stage (pT) which describes the tumour, nodal stage (pN) which describes any lymph nodes examined, and metastatic stage (pM) which describes tumour cells that have spread to other parts of the body. Most pathology reports will include information about the tumour and nodal stages. The overall pathologic stage is important because it helps your doctor determine the best treatment plan and predict the outlook for recovery.

Tumour stage (pT)

- T0: No evidence of primary tumour.

- T1: The tumour is 2 cm (about 0.8 inches) or smaller in its greatest dimension and confined to the thyroid.

- T1a: The tumour is 1 cm (about 0.4 inches) or smaller.

- T1b: The tumour is larger than 1 cm but not larger than 2 cm.

- T2: The tumour is larger than 2 cm but not larger than 4 cm (about 1.6 inches) and is still inside the thyroid.

- T3: The tumour is larger than 4 cm or has minimal extension beyond the thyroid gland.

- T3a: The tumour is larger than 4 cm but is still confined to the thyroid.

- T3b: The tumour shows gross extrathyroidal extension (it has spread into the muscles outside of the thyroid).

- T4: This indicates advanced disease.

- T4a: The tumour extends beyond the thyroid capsule to invade subcutaneous soft tissues, the larynx (voice box), trachea (windpipe), esophagus (food pipe), or recurrent laryngeal nerve (a nerve that controls the voice box).

- T4b: The tumour invades prevertebral space (area in front of the spinal column), and encases the carotid artery or the mediastinal vessels (major blood vessels).

Nodal stage (pN)

- N0: No regional lymph node metastasis (the cancer hasn’t spread to nearby lymph nodes).

- N1: There is metastasis to regional lymph nodes (near the thyroid).

- N1a: Metastasis is limited to lymph nodes around the thyroid (pretracheal, paratracheal, prelaryngeal/Delphian, and/or perithyroidal lymph nodes).

- N1b: Metastasis to other cervical (neck) or superior mediastinal lymph nodes (lymph nodes in the upper chest).