by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

July 3, 2025

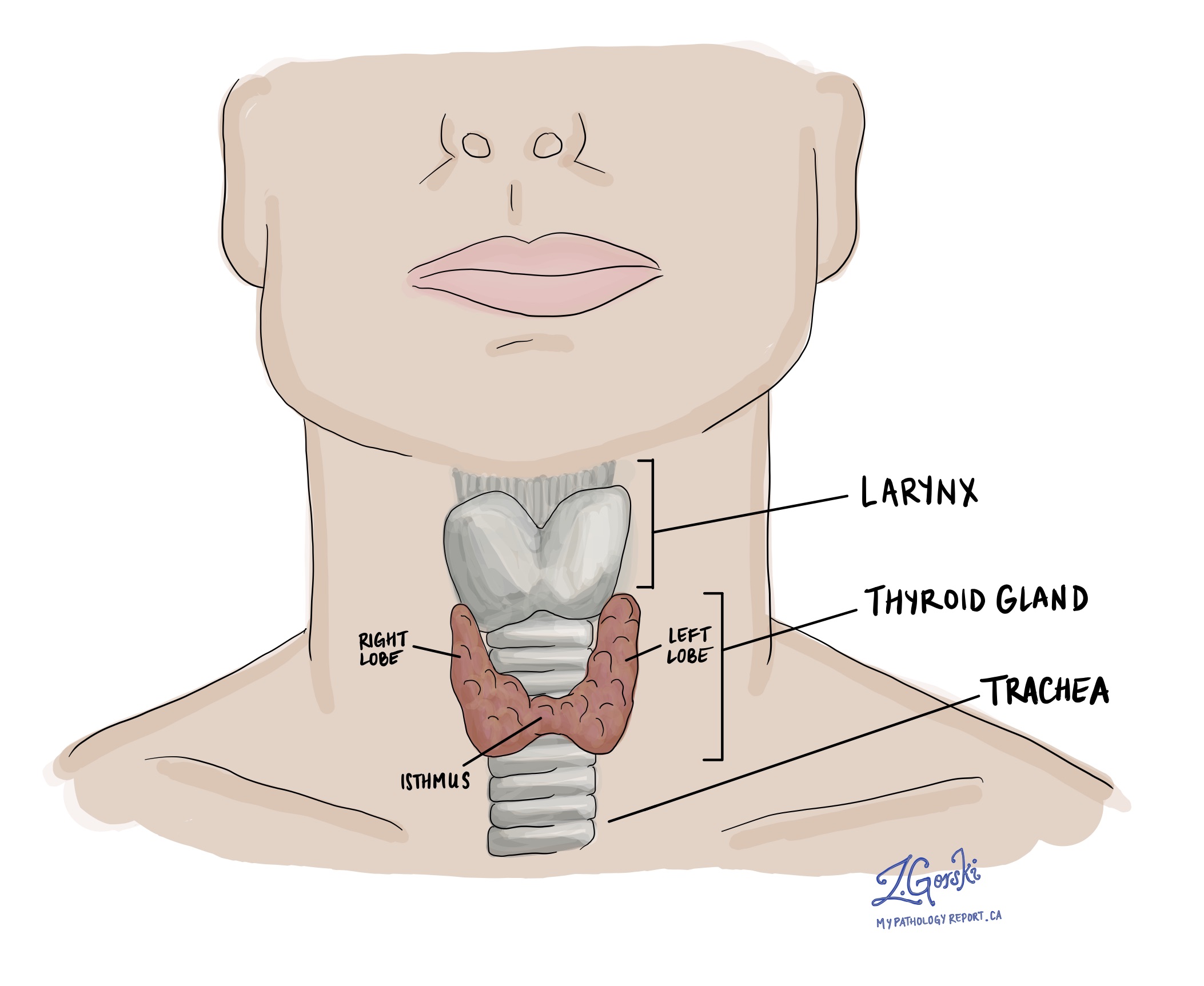

Follicular thyroid carcinoma is a type of thyroid cancer that starts from follicular cells, the cells in the thyroid gland responsible for making thyroid hormones. It is considered a well-differentiated carcinoma, meaning the tumour cells still resemble normal thyroid cells under the microscope, but unlike benign thyroid tumours, these cancer cells show invasion into nearby tissues or blood vessels.

Follicular thyroid carcinoma is relatively uncommon and accounts for about 5–15% of all thyroid cancers. It is not the same as papillary thyroid carcinoma, which is the most common type of thyroid cancer. Unlike papillary thyroid carcinoma, follicular thyroid carcinoma does not exhibit the typical nuclear features seen in papillary tumours and is less likely to spread to lymph nodes; however, it can metastasize through the bloodstream to organs such as the lungs or bones.

What are the subtypes of follicular thyroid carcinoma?

Pathologists divide follicular thyroid carcinoma into three subtypes based on how much the tumour has invaded surrounding tissues:

-

Minimally invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma

-

Shows limited growth into the tumour capsule (a thin layer of tissue surrounding the tumour).

-

Does not invade nearby blood vessels.

-

Has the best prognosis.

-

-

Encapsulated angioinvasive follicular thyroid carcinoma

-

Invades both the capsule and nearby blood vessels.

-

More likely to spread to distant sites, such as the lungs or bones.

-

Prognosis depends on the number of blood vessels involved.

-

-

Widely invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma

-

Grows deeply into the surrounding thyroid tissue or outside the gland.

-

Often invades many blood vessels.

-

Has the highest risk of spreading and a worse prognosis.

-

What are the symptoms of follicular thyroid carcinoma?

Most people with follicular thyroid carcinoma first notice a painless lump in the neck, usually in the region of the thyroid gland. Many cases are found incidentally during a routine physical exam or imaging study, such as an ultrasound.

In some cases, especially when the tumour is large, it may cause symptoms such as:

-

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia).

-

Hoarseness.

-

Pressure or tightness in the neck.

Rarely, follicular thyroid carcinoma may produce too much thyroid hormone, leading to hyperthyroidism, with symptoms such as nervousness, weight loss, or increased heart rate. In about 5–10% of cases, the cancer has already spread to other parts of the body by the time it is diagnosed. In these cases, symptoms may come from the site of spread, such as bone pain or shortness of breath.

What causes follicular thyroid carcinoma?

The exact cause is unknown, but several risk factors have been linked to follicular thyroid carcinoma:

-

Iodine deficiency: Areas with low iodine in the diet have higher rates of this cancer.

-

Radiation exposure: Especially during childhood.

-

Genetic syndromes: Some inherited conditions, such as PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome (Cowden syndrome), DICER1 syndrome, Werner syndrome, and Carney complex.

These syndromes may cause multiple types of tumours, including follicular thyroid carcinoma. Most cases, however, are sporadic, meaning they occur by chance.

How is follicular thyroid carcinoma diagnosed?

Diagnosis usually begins with thyroid imaging (such as ultrasound) and fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB). However, the definitive diagnosis can only be made after the tumour is surgically removed and examined under the microscope. This is because follicular thyroid carcinoma is diagnosed based on the presence of invasion—either into the capsule or into nearby blood vessels—which cannot be seen in a biopsy sample.

What does follicular thyroid carcinoma look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, follicular thyroid carcinoma is made up of follicular cells arranged in round structures called follicles, or in solid or trabecular patterns. The cells resemble those in follicular adenoma, a benign tumour, but the key difference is that in carcinoma, the cells break through the capsule or enter nearby blood vessels.

Other features include:

-

No nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma (such as nuclear grooves or pseudoinclusions).

-

Low numbers of dividing cells (low mitotic activity).

-

No tumour necrosis (dead tumour tissue), although infarction from biopsy may be seen.

A diagnosis of follicular thyroid carcinoma requires the identification of at least one focus of capsular or vascular invasion. The amount and extent of invasion influence the prognosis.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry is a special test that pathologists use to help diagnose and classify tumours. It works by using antibodies to detect specific proteins made by the tumour cells. These proteins can help confirm that the tumour started in the thyroid and may also provide clues about how the tumour is likely to behave.

For follicular thyroid carcinoma, immunohistochemistry typically shows the following:

-

Thyroglobulin: This protein is made by normal thyroid cells and is usually found in the cytoplasm (the inside of the cell). Most follicular thyroid carcinomas are positive for thyroglobulin, which confirms that the tumour came from thyroid follicular cells.

-

Thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and PAX8: These are nuclear proteins that are also commonly found in thyroid cells. Most follicular thyroid carcinomas show strong nuclear staining for both.

-

Cytokeratins (CAM5.2, CK7): These proteins help support the structure of cells and are usually present in follicular thyroid carcinoma. They help distinguish thyroid tumours from other types of cancer.

-

Calcitonin and CK20: These markers are negative in follicular thyroid carcinoma, which helps rule out other types of thyroid cancer (such as medullary thyroid carcinoma or metastatic cancers).

-

Ki-67: This protein helps measure how quickly the tumour cells are dividing. Most follicular thyroid carcinomas have a low Ki-67 index (less than 5%), indicating that the tumour cells are not dividing rapidly. A higher Ki-67 index may suggest a more aggressive tumour or raise concern for a different type of cancer, such as poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma.

These tests help pathologists confirm that the tumour started in the thyroid and rule out other possibilities. However, they do not reliably distinguish between follicular adenoma (a benign tumour) and follicular thyroid carcinoma because both may show similar staining. The final diagnosis still depends on whether the tumour has invaded surrounding tissue or blood vessels, which must be seen under the microscope.

Molecular testing

Molecular testing looks for changes (mutations or rearrangements) in the DNA of the tumour cells. These tests are often conducted using a method called next-generation sequencing (NGS), which enables the simultaneous testing of multiple genes. Molecular testing is sometimes used to help understand how a thyroid tumour developed and how it might behave.

In follicular thyroid carcinoma, the most common molecular findings include:

-

RAS mutations: Found in up to 30% of follicular thyroid carcinomas. These mutations affect genes that control cell growth (such as NRAS, HRAS, or KRAS). RAS mutations are common in both benign and malignant follicular-patterned thyroid tumours and are not specific for cancer.

-

PAX8::PPARG gene rearrangement: This abnormal fusion between two genes is found in 10–40% of follicular thyroid carcinomas. Tumours with this change may occur in younger patients and may be more likely to show aggressive behaviour.

-

TERT promoter mutations: Found in about 15% of follicular thyroid carcinomas, especially those with distant metastases (spread to other organs). These mutations are linked to more advanced disease and worse prognosis.

-

PIK3CA and PTEN mutations: These are part of a signalling pathway that helps control cell growth. These mutations are more common in follicular thyroid carcinoma than in benign thyroid tumours.

-

EIF1AX mutations: Found in a small number of cases, often in combination with RAS mutations.

-

DICER1 and NF1 mutations: Rare but may be seen in tumours related to inherited syndromes.

-

TSHR (thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor) mutations: Rarely seen, especially in tumours that produce excess thyroid hormone (causing hyperthyroidism).

It’s important to know that no single genetic mutation confirms the diagnosis of follicular thyroid carcinoma. The diagnosis is still made by carefully examining the tumour under the microscope. Molecular testing provides additional information that may help predict the behaviour of the tumour and guide future treatment.

How is follicular thyroid carcinoma treated?

The main treatment is surgery to remove part or all of the thyroid gland. This may be followed by radioactive iodine therapy to destroy any remaining thyroid tissue or cancer cells.

Other treatments may include:

-

Thyroid hormone replacement to maintain normal hormone levels and suppress tumour growth.

-

Radiation therapy or chemotherapy for advanced or metastatic disease.

-

Targeted therapies for tumours with specific genetic mutations.

Your treatment plan will depend on the tumour subtype, size, spread, and other risk factors.

What is the prognosis for follicular thyroid carcinoma?

The prognosis depends on the extent of invasion, tumour size, and whether the cancer has spread:

-

Minimally invasive tumours have an excellent prognosis, with survival rates over 95%.

-

Encapsulated angioinvasive tumours have a higher risk of spread. If only a few blood vessels are involved (< 4), the prognosis is still good.

-

Widely invasive tumours carry the highest risk of spread and recurrence and have a less favorable prognosis.

-

The presence of distant metastases (to the lungs or bones) is the most important factor in long-term survival.

Genetic changes, such as TERT promoter mutations, are also associated with worse outcomes.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What type of follicular thyroid carcinoma do I have?

-

Was there evidence of capsular or vascular invasion?

-

Has the cancer spread beyond the thyroid?

-

Will I need radioactive iodine therapy?

-

What is my long-term prognosis?

-

Should I have genetic testing for hereditary syndromes?

-

How often will I need follow-up tests or scans?

-

Will I need thyroid hormone replacement for life?