by Trevor A. Flood, MD FRCPC

February 6, 2025

Prostatic adenocarcinoma is the most common type of prostate cancer. This type of cancer may also be described as acinar adenocarcinoma because it is made up of groups of tumour cells forming small glands called acini. It develops from epithelial cells normally found in the prostate gland. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate is a relatively common cancer among older men, and the risk of developing this type of cancer increases after a man turns 50 years old.

Is prostatic adenocarcinoma an aggressive disease?

Prostatic adenocarcinoma can appear and progress very differently in each person. Many tumours grow slowly. Some men can live many years before the cancer is detected. Some tumours are aggressive. Aggressive cancer should be treated right away.

What are the symptoms of prostate cancer?

Many cases of prostate cancer do not cause symptoms and are only detected because of an elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level in the blood. PSA is a protein produced by prostate cells, and an elevated level can indicate the presence of prostate cancer, although it is not specific to cancer.

Some men may experience urinary symptoms such as difficulty urinating, weak urine flow, or frequent urination, especially at night. However, these symptoms are also common in non-cancerous conditions like benign prostatic hyperplasia. Less commonly, prostate cancer can cause blood in the urine or semen, erectile dysfunction, or discomfort in the pelvic area.

If prostate cancer spreads beyond the prostate, it often affects the bones, leading to bone pain, fractures, or weakness. Other sites of metastasis include the lungs, liver, and adrenal glands. Advanced prostate cancer can cause significant symptoms, impacting a patient’s quality of life.

What are the risk factors for developing prostatic adenocarcinoma?

The risk factors for developing prostatic adenocarcinoma include older age, a family history of prostate cancer, African or Caribbean ethnicity, and obesity.

How is the diagnosis of prostatic adenocarcinoma made?

Most tumours in the prostate are found after a doctor manually examines your prostate gland. This procedure is called a digital rectal examination. If an unusual lump is found, the next step is to take several small tissue samples from the prostate in a procedure called a core needle biopsy. Most biopsies usually involve 10 to 15 samples of tissue taken from different parts of the prostate. A biopsy can also be done after a blood test shows high levels of the prostate-specific antigen (PSA).

Your pathologist will then examine the tissue samples under a microscope. What they see (the microscopic features) will help them predict how the disease will behave. These same features will help you and your doctors decide which treatment options are best for you. These options may include active surveillance, radiation, or surgery to remove the tumour.

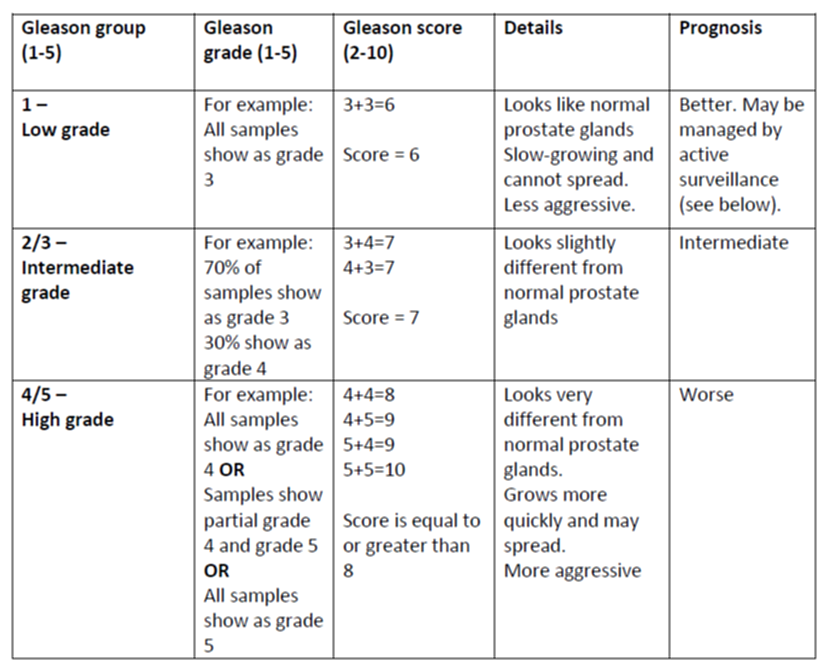

Gleason grade, Gleason score, and Gleason group

Your prostatic adenocarcinoma pathology report will likely contain much information about the Gleason grade and score. Both are numeric scales. The Gleason grade ranges from 1 to 5, and the Gleason score ranges from 2 to 10. Both are important because they help predict the tumour’s behaviour over time.

Gleason grade

Your pathologist will decide the Gleason grade after examining the tissue under the microscope. The grade is based on how different the tumour cells look compared to normal glands in the prostate. Your pathologist will then give the tumour a number between 1 and 5. Tumours that look similar to normal glands are given a lower number. These tumours tend to be slow-growing and less aggressive. Tumours that do not look like normal glands are given a higher number and tend to be more aggressive. These tumours can grow quickly and spread.

Gleason grade 1 and 2 tumours are not typically diagnosed. These grades are noted as part of your health history only. As a result, Gleason grades range from 3-5 (instead of 1-5), and Gleason scores range from 6-10 (instead of 2-10).

Gleason score

The Gleason score is calculated by adding up the two most common Gleason grade numbers in your tumour. For example, if your tumour is made up of 70% Gleason grade 3 and 30% Gleason grade 4, then your Gleason score would be 3+4=7. If only one Gleason grade is seen then the primary and secondary patterns are given the same grade. For example, if your tumour is made up 100% of Gleason grade 3, then your Gleason score is 3+3=6. The Gleason score is important because it can be used to predict the behaviour of the tumour.

Gleason group

The prostate cancer Gleason Grade group is a new grading system based on information from the Gleason score. The Grade groups range from 1 to 5. See the table below for more information. All tumours within a Gleason Grade group are likely to behave similarly, and patients within the same group have a similar prognosis.

Understanding biopsy cores and tumour volume

Prostate biopsies typically involve taking multiple tissue samples from different parts of the prostate gland. Each sample is called a core. If cancer is found in any of the cores, the pathology report will include specific details about how much cancer is present.

The report should list:

- The total number of cores taken.

- The number of cores that contain cancer.

- The percentage of each core that is involved with cancer.

- An estimate of the total amount of prostate tissue examined that contains cancer.

This type of tumour quantification is performed only on biopsy samples. It helps doctors understand the extent of cancer involvement before surgery or other treatments. The volume of cancer in biopsy cores can provide helpful information about the tumour’s aggressiveness and help guide treatment decisions.

How is tumour involvement measured?

In most cases, the pathology report will specify the number of cores with cancer (positive cores) out of the total taken, except in cases where fragmentation prevents an accurate count.

Additionally, the estimated percentage of tumour involvement and/or the measurement of tumour length in millimeters is often reported. Some treatment plans, such as active surveillance, may exclude patients if a core shows more than 50% cancer involvement. For this reason, how tumour volume is reported can impact eligibility for specific management options.

Cancerous areas in a biopsy core are sometimes not continuous but appear in separate spots. In such cases, the total involvement may be reported in two ways:

- Adding up the separate areas (e.g., if a 20-mm core has 5% cancer at both ends, it may be recorded as 10% involvement).

- Reporting the longest span of cancer (e.g., if cancer is scattered throughout a 20-mm core, the total involvement may be described as 100%).

Research suggests that recording the cancer length from one end to the other correlates better with the amount of tumour found in the prostate after surgery. For example, some studies estimate that in 75-80% of cases with discontinuous foci in biopsy cores, the foci likely represent the same tumour. For this reason, different reporting methods may be used to provide the most accurate assessment.

Tumour quantification after surgery to remove the prostate gland

Tumour quantification is the percentage of the prostate replaced by cancer cells, which estimates the tumour’s size. This information will be reported after the entire prostate gland is removed in a procedure called a prostatectomy. Tumour quantification is important because studies have shown that larger-volume tumours are more likely to recur or metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes or other body parts.

Extraprostatic extension

Extraprostatic extension describes cancer cells that have moved outside the prostate and into the surrounding tissue. If cancer cells are seen in the tissue outside the prostate, they will be described in your report. Extraprostatic extension is associated with a worse prognosis and is used to determine the tumour stage.

Seminal vesicle invasion

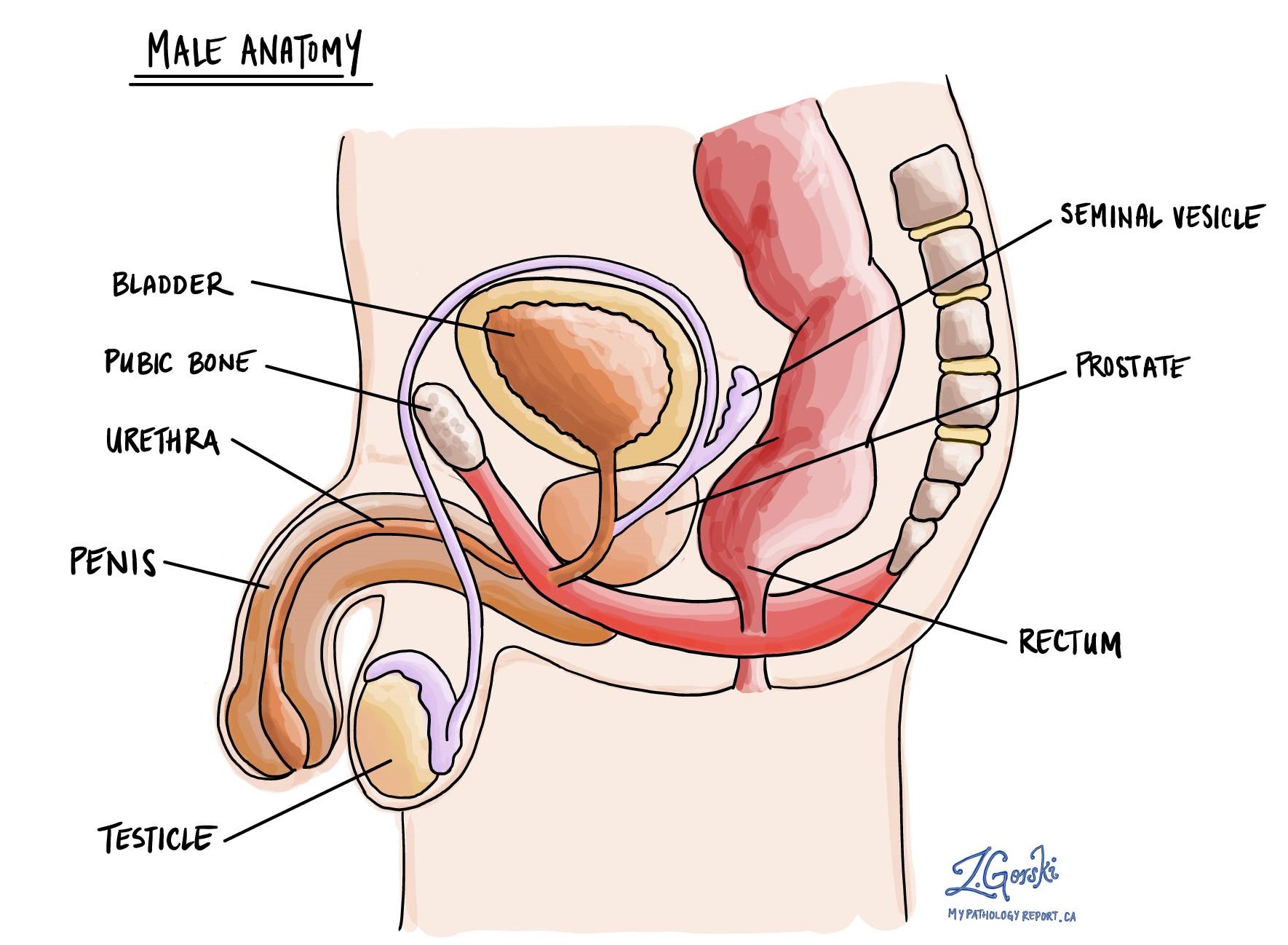

The seminal vesicles are organs located behind the bladder and above the prostate. Each person has two seminal vesicles, one on each side of the prostate. These organs produce and store the fluid sent to the prostate to feed and move sperm. Seminal vesicle invasion means that cancer cells have spread directly from the prostate into the seminal vesicles. Seminal vesicle invasion is associated with a worse prognosis and is used to determine the tumour stage.

Bladder neck invasion

The bladder rests above the prostate gland. Bladder neck invasion means that cancer cells have spread directly from the prostate into the lower part of the bladder, known as the bladder neck. Invasion of the bladder neck is associated with a worse prognosis and is used to determine the tumour stage.

Perineural invasion

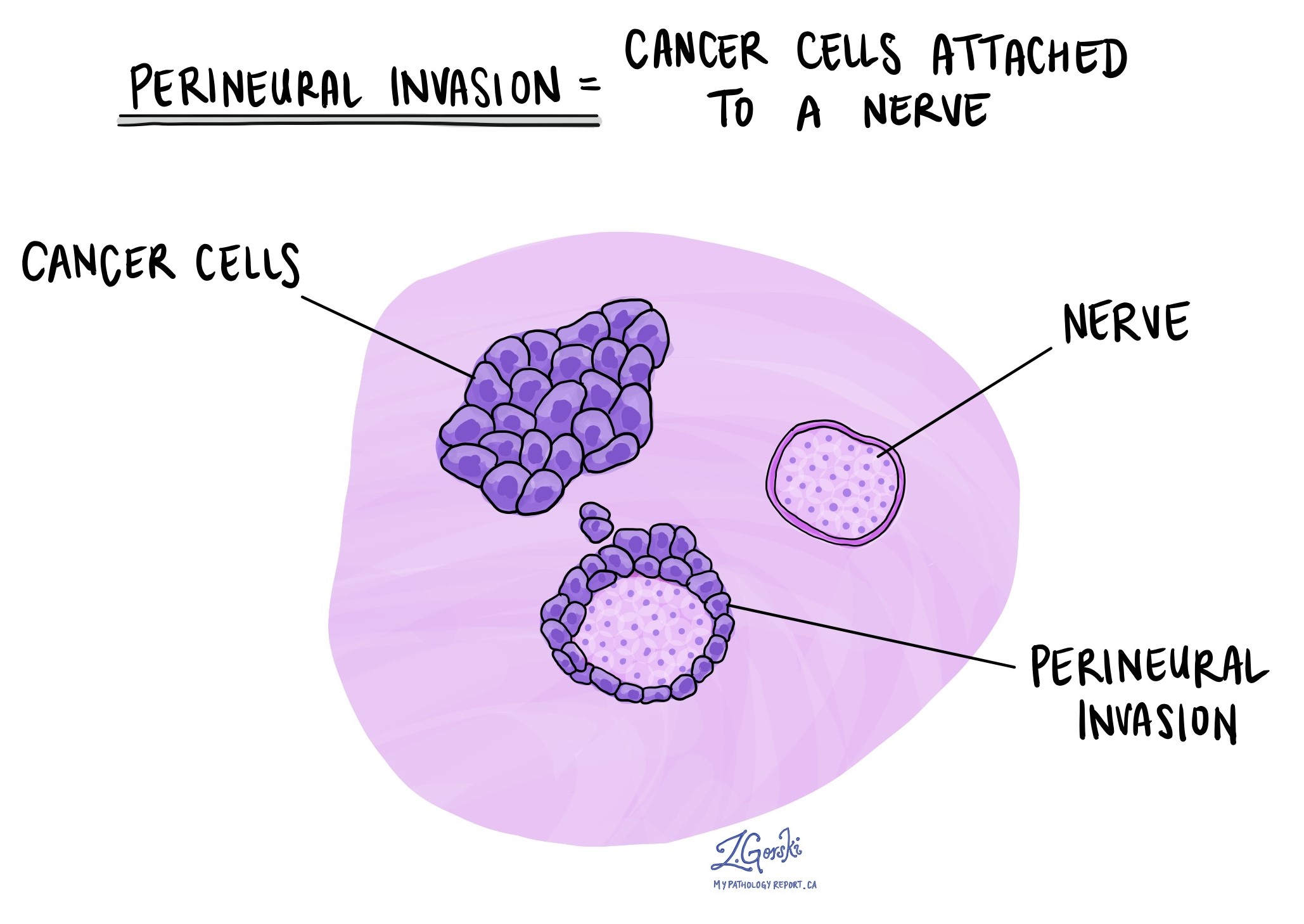

Pathologists use the term “perineural invasion” to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that specifically refers to cancer cells inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. Perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic channel. Blood vessels, thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, contrast with lymphatic channels, which carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic channels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it spreads cancer cells to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the lungs, via the blood or lymphatic vessels.

Margins

Margins refer to the edges of the tissue removed during surgery. In prostate cancer, margins are assessed only after a radical prostatectomy, where the entire prostate gland is removed. Pathologists examine the margins to determine if cancer cells are present at the edge of the removed tissue.

There are different types of margins in a radical prostatectomy:

- Apical margin: Located at the tip of the prostate.

- Bladder neck margin: Where the prostate meets the bladder.

- Posterior margin: Near the rectum.

A positive margin means cancer cells are found at the edge of the removed tissue, suggesting that some cancer may remain in the body. A negative margin means no cancer cells are present at the edge, indicating the tumour was fully removed. Some pathology reports may also specify the distance between the tumour and the margin, even when margins are negative.

The margin status is important because a positive margin increases the risk of cancer recurrence. Your doctor will use this information to determine if additional treatment, such as radiation therapy, is needed.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer can spread to lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels, so pathologists examine them under a microscope to check for cancer cells. This spread is called metastasis.

Cancer cells usually spread first to nearby lymph nodes, but distant nodes can also be involved. Doctors typically remove lymph nodes near the tumour, and those farther away are only taken if they are enlarged or suspected to contain cancer.

If lymph nodes are removed, your pathology report will describe whether they contain cancer. “Positive” means cancer cells were found, while “negative” means no cancer was detected. If cancer is present, the report may also include the size of the largest area of cancer, called a focus or deposit. If the cancer has spread beyond the lymph node into surrounding tissue, it is called extranodal extension.

Lymph node involvement is important for staging (pN stage) and helps predict the risk of cancer spreading to other parts of the body. This information helps doctors decide if additional treatment, such as chemotherapy, radiation, or immunotherapy, is needed.

Molecular markers for prostatic adenocarcinoma

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a laboratory test that allows doctors to examine the genetic material inside cells. This test looks for changes such as mutations or fusions in genes that may be linked to cancer.

NGS is sometimes performed in cases of prostatic adenocarcinoma, especially when the cancer is advanced or has stopped responding to standard treatments. However, the specific genes tested can vary by institution. Understanding the genetic changes in a tumour can provide important information about prognosis and potential treatment options.

Androgen receptor (AR)

The androgen receptor is a protein found inside prostate cells that allows them to respond to male hormones (androgens), such as testosterone. Prostatic adenocarcinoma depends on androgens for growth, and most treatments work by blocking their effects. In some cases, changes in the androgen receptor gene can make the cancer resistant to treatment. One such change is AR-V7, a variant that makes the cancer less likely to respond to hormone-blocking drugs. Testing for androgen receptor variants may help guide treatment decisions.

BRCA1 and BRCA2

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are genes that help repair damaged DNA. When these genes are mutated, cells accumulate DNA damage, which can lead to cancer. While BRCA mutations are best known for increasing the risk of breast and ovarian cancer, they can also increase the risk of developing aggressive prostate cancer. A positive test result for BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations may indicate a higher likelihood of cancer progression and can help determine if targeted therapies, such as PARP inhibitors, may be beneficial.

PTEN

PTEN is a tumour suppressor gene that helps regulate cell growth. Loss of PTEN function can lead to uncontrolled cell division and cancer progression. PTEN mutations or deletions are found in many cases of advanced prostatic adenocarcinoma. Testing for PTEN loss can provide information about the tumour’s aggressiveness and potential response to specific treatments.

ATM

ATM is a gene that plays a key role in repairing DNA damage. Mutations in ATM can increase the risk of developing prostate cancer and may also make tumours more sensitive to specific treatments, such as radiation therapy and DNA-damaging drugs. A positive test result for an ATM mutation may help doctors decide whether a patient is a candidate for specific therapies.

PALB2

PALB2 works together with BRCA2 to help repair damaged DNA. While PALB2 mutations are well known for increasing the risk of breast cancer, some studies suggest they may also contribute to prostate cancer risk. Tumours with PALB2 mutations may respond better to PARP inhibitors, which target cancer cells with defective DNA repair mechanisms.

TMPRSS2-ERG fusion

TMPRSS2-ERG is a genetic rearrangement found in about 30-50% of prostate cancers. It occurs when the androgen-controlled TMPRSS2 gene fuses with the ERG oncogene, which promotes cancer growth. The presence of this gene fusion can help confirm a diagnosis of prostatic adenocarcinoma and may provide additional information about the tumour’s behaviour.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

The pathologic stage for prostatic adenocarcinoma is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT)

Your pathologist will assign a tumour stage of T2 to T4 based on their observations from examining your prostate specimen under the microscope. The tumour stage reflects the extent to which the cancer cells have spread beyond the prostate.

- T2 – The tumour is found inside the prostate only.

- T3 – The cancer cells have spread outside of the prostate and into the fat, seminal vesicles, and/or into the bladder neck.

- T4 – The cancer cells have spread into other nearby organs or tissues such as the rectum or pelvic wall.

Nodal stage (pN)

Prostatic adenocarcinoma is given a nodal stage of N0 or N1 based on the presence of cancer cells in a lymph node. If no lymph nodes contain cancer cells, the nodal stage is N0. If no lymph nodes are sent for pathological examination, the nodal stage cannot be determined, and it is listed as NX.

What does active surveillance mean?

Active surveillance is a treatment option for men who have low-grade (Gleason score 3+3=6 or Grade group 1) prostate cancer detected by a biopsy. Since the tumour is growing slowly, there is no need to remove it right away because it likely poses no risk to the patient. Active surveillance avoids invasive treatments for low-risk cancer that is growing slowly.

Active surveillance involves monitoring the patient with:

- Regular prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood tests.

- Regular manual examinations of the prostate (digital rectal examination).

- Occasional core needle biopsies.

Patients will be offered treatment (surgery or radiation) at the first sign that the prostate cancer has progressed or if it has changed into a more aggressive type of tumour (pathologists call this ‘transformation’).

What is the prognosis for patients diagnosed with prostatic adenocarcinoma?

The prognosis for patients with prostatic adenocarcinoma depends on several factors, including the stage of the cancer, the Gleason score, and whether the cancer has spread beyond the prostate. The most important predictors of cancer recurrence are the tumour grade and whether the cancer has spread outside the prostate gland.

Risk factors identified on biopsy, such as high tumour volume, perineural invasion, and extensive core involvement, are associated with a higher likelihood of advanced disease. After prostatectomy, additional factors, including extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, lymph node metastasis, and positive surgical margins, play a key role in prognosis.

Genetic changes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, PTEN loss, and high Ki-67 expression are also associated with more aggressive tumours. Ongoing research continues to refine how genetic and molecular markers contribute to risk stratification and treatment decisions.