By Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

December 5, 2024

Invasive melanoma is a type of skin cancer that begins in the melanocytes, the cells responsible for producing pigment in the skin. Unlike some other forms of skin cancer, invasive melanoma can grow deeper into the skin and spread to other parts of the body if not treated early. It is the most serious form of skin cancer, but when detected and treated early, outcomes can be very good.

Melanomas often appear as unusual spots on the skin that may change in size, shape, or colour over time. They can arise in any body part but are most commonly found in areas exposed to the sun, such as the back, legs, arms, and face. Early recognition and treatment are crucial for preventing the cancer from spreading.

What causes invasive melanoma?

Most invasive melanomas in the skin are caused by long-term exposure to UV radiation, typically from the sun. However, other sources of UV light, such as tanning beds, can have a similar effect. UV radiation causes genetic changes in the melanocytes, leading to cancer development. Melanomas not caused by long-term sun exposure, such as those arising from a mole, are much less common.

How is the diagnosis of invasive melanoma made?

The diagnosis of invasive melanoma begins with a careful skin examination by a healthcare professional. The next step is usually a biopsy if a suspicious lesion is identified. During a biopsy, a small piece of tissue is removed from the lesion so a pathologist can examine it under a microscope.

The pathologist looks for specific features in the tissue that indicate melanoma, such as irregular cell shapes, unusual patterns of growth, and invasion into deeper layers of the skin. If melanoma is confirmed, the pathologist also provides additional information in the pathology report, including the tumour’s thickness, ulceration, and whether the melanoma has invaded nearby structures like lymphatic vessels or nerves. These features are explained in greater detail in the sections below.

Special tests such as immunohistochemistry may sometimes be performed on the tissue sample. These tests use antibodies to detect proteins commonly found in melanoma cells, which can help confirm the diagnosis and differentiate melanoma from other types of skin growths.

If there is concern that the melanoma has spread beyond the skin, imaging tests such as CT or PET scans may be performed to check for the involvement of lymph nodes or other organs. Additionally, a sentinel lymph node biopsy may be done to determine whether cancer cells have spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Histologic types of invasive melanoma

Invasive melanoma of the skin is divided into histologic types based on the way the tumour cells grow and spread through the skin. The most common types of invasive melanoma are superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanoma, and lentigo maligna melanoma.

Superficial spreading melanoma

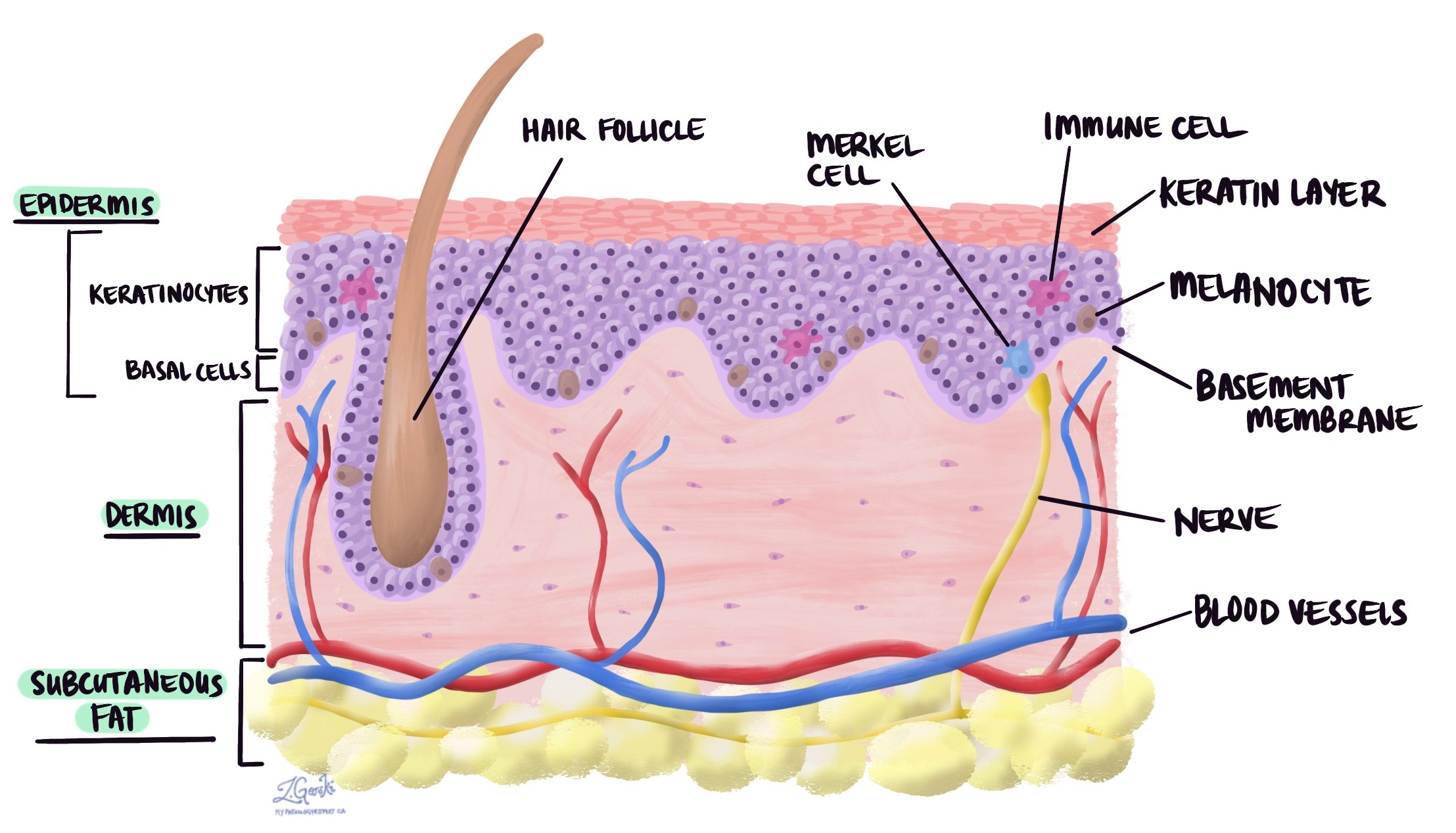

In superficial spreading melanoma, the tumour cells spread along the epidermis and in the most superficial parts of the dermis (the layer of skin just below the epidermis). The surrounding skin often shows changes associated with moderate sun damage, including solar elastosis. This type of invasive melanoma usually starts from a non-invasive kind of skin cancer called melanoma in situ.

Nodular melanoma

In nodular melanoma, most tumour cells are found in the dermis (the layer of skin just below the epidermis). They are often found in large groups that may be described as sheets or nests. Tumour cells may also be found in the epidermis, overlying the large groups of tumour cells. Unlike other types of melanoma, nodular melanoma grows more quickly and is more likely to spread to other body parts.

Lentigo maligna melanoma

In lentigo maligna melanoma, the tumour cells are found primarily along the border between the epidermis and the dermis in an area called the dermal-epidermal junction. Tumour cells will also be found in the superficial dermis (just below the epidermis). In contrast to the superficial spreading type of melanoma, the skin surrounding lentigo maligna melanoma will show changes associated with severe sun exposure, including extensive solar elastosis. Lentigo maligna melanoma often starts from a non-invasive type of skin cancer called lentigo maligna (also known as melanoma in situ).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry is a special test that helps pathologists identify specific proteins in tumour cells. This test is particularly useful for confirming the diagnosis of invasive melanoma and distinguishing it from similar-looking tumours that can arise in the skin. In invasive melanoma, tumour cells usually test positive for markers commonly found in melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells in the skin.

Markers such as SOX10 and MITF are typically positive in invasive melanoma and help confirm that the tumour arises from melanocytes. Other markers, including HMB-45, MelanA, and MART1, also highlight the tumour cells, but they may occasionally stain normal skin structures as well.

Some of these markers may not be expressed in more aggressive parts of the tumour, making it harder to identify the tumour cells. In such cases, a dual stain using Ki67 (a marker of cell growth) and MelanA can help pinpoint areas where the tumour is actively growing, even in tumours with significant inflammation.

Some invasive melanomas may also test positive for a marker called PRAME, which can support the diagnosis. In some instances, immunohistochemistry can detect mutations in the BRAF gene (p.V600E), which is important because these mutations can guide targeted therapy. Additionally, loss of a protein called p16 is often seen in invasive melanoma, especially in areas where the tumour is growing deeper into the skin.

Tumour thickness

All invasive melanomas start in the epidermis, a thin layer of tissue on the skin’s surface. As the tumour grows, the cells spread into the layers of tissue below the epidermis, including the dermis and subcutaneous adipose tissue. The spread of tumour cells in this way is called invasion. Tumour thickness (also known as Breslow’s thickness) is the distance from the epidermis to the deepest point of invasion. The tumour thickness is important because it determines the pathologic tumour stage (pT) and because thicker tumours are more likely to spread to other body parts, such as lymph nodes and the lungs.

Ulceration

Ulceration is a type of tissue damage that results in the loss of cells on the surface of a tissue. For skin tumours such as invasive melanoma, ulceration refers to the loss of cells in the epidermis over the tumour. Invasive melanomas that cause ulceration are associated with a worse prognosis. Ulceration is also used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

Mitotic rate

A mitotic figure (or mitosis) is a cell that is dividing to create two new cells. For tumours such as invasive melanoma, pathologists count the number of mitotic figures in a specified area of tissue (for example, 1 mm2), and the count is called the mitotic rate. The mitotic rate is important because tumours with a higher rate grow more quickly and are more likely to spread to other parts of the body.

Microsatellites

For invasive melanoma, a microsatellite is a group of tumour cells that have spread from the primary tumour (where the tumour started) to a nearby area of skin. Another name for a microsatellite is cutaneous metastasis. Microsatellites are important because they increase the pathologic nodal stage (pT).

Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)

The term tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) describes specialized immune cells called lymphocytes surrounding or spreading into the tumour. Current evidence shows that TILs can kill and remove tumour cells. For this reason, the more TILs seen, the better.

Most pathologists will categorize the number of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes as follows:

- No tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes were identified.

- Non-brisk (very few tumour infiltrating lymphocytes)

- Brisk (lots of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes)

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion means cancer cells are seen inside a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long, thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. The lymphatic vessels connect with small immune organs called lymph nodes throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because cancer cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other body parts, such as lymph nodes or the lungs.

Neurotropism

Neurotropism (also known as perineural invasion) is a term pathologists use to describe cancer cells attached to or inside a nerve. Nerves are like long wires made up of groups of cells called neurons. They are found all over the body and are responsible for sending information (such as temperature, pressure, and pain) between the body and brain. Neurotropism is important because cancer cells can use the nerve to spread into surrounding organs and tissues. This increases the risk that the tumour will regrow after surgery.

Tumour regression

Tumour regression is the gradual disappearance of tumour cells from an area where tumour cells were previously found. The tumour cells are often replaced by immune cells or scar tissue called fibrosis. Tumour regression is believed to be caused by immune cells that attack and kill the tumour cells. Invasive melanoma can show partial or complete tumour regression.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs located throughout the body that help fight infections and filter harmful substances. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour to nearby lymph nodes through tiny lymphatic vessels. When this happens, it is called a metastasis.

Lymph node removal and examination: Lymph nodes near the tumour are often removed and examined under a microscope to check for cancer cells. These are typically the first lymph nodes affected, but if there is concern about cancer spreading further, lymph nodes farther away may also be removed, especially if they are enlarged.

If lymph nodes are removed, the pathologist will examine them and include the following details in the pathology report:

- The total number of lymph nodes examined.

- Where the lymph nodes were located.

- The number of lymph nodes containing cancer cells (if any).

- The size of the largest focus or deposit of cancer cells

This information is important for determining the pathologic nodal stage (pN) and assessing the risk of cancer spreading to other body parts. Finding cancer in a lymph node may influence decisions about additional treatment, such as immunotherapy, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy.

Sentinel lymph node: The sentinel lymph node is the first lymph node that receives fluid drainage from the tumour. It is usually the first place where cancer cells spread.

Non-sentinel lymph nodes: Non-sentinel lymph nodes are the lymph nodes located after the sentinel lymph node. Cancer cells typically spread to these lymph nodes only after passing through the sentinel lymph node.

Extranodal extension: Lymph nodes are surrounded by a thin capsule of tissue. Extranodal extension occurs when cancer cells break through the capsule and spread into the surrounding tissue. This is significant because it increases the risk of the cancer regrowing in the same area after surgery and may lead to recommendations for additional treatments.

The examination of lymph nodes provides essential information about the extent of melanoma and helps guide treatment decisions. If you have questions about your pathology report or what the lymph node findings mean, your doctor can explain how this information applies to your care.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of a tissue cut when removing a tumour from the body. The margins described in a pathology report are very important because they tell you if the entire tumour was removed or if some of the tumour was left behind. The margin status will determine what (if any) additional treatment you may require.

Pathologists carefully examine the margins to look for tumour cells at the cut edge of the tissue. If tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, the margin will be described as positive. If no tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, a margin will be described as negative. Even if all of the margins are negative, some pathology reports will also measure the closest tumour cells to the cut edge of the tissue.

A positive (or very close) margin is important because it means that tumour cells may have been left behind in your body when the tumour was surgically removed. For this reason, patients with a positive margin may be offered another surgery to remove the rest of the tumour or radiation therapy to the area of the body with the positive margin.

Pathologic stage for invasive melanoma

The pathologic stage of invasive melanoma is determined using the TNM system, a standard classification system that describes the extent of cancer in the body. TNM stands for:

- T (tumour): Describes the size and depth of the primary tumour.

- N (nodes): Indicates whether cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- M (metastasis): Refers to the presence of cancer in distant parts of the body.

Staging is critical for skin cancer because it helps doctors understand the extent of the disease, plan treatment, and estimate prognosis. Below is a summary of the T and N stages used to describe invasive melanoma.

T stages (tumour stages)

- Tis: The melanoma is “in situ,” meaning it is confined to the top layer of skin and has not invaded deeper layers.

- T1: The tumour is no more than 1 millimetre (mm) thick.

- T1a: The tumour is no more than 1 mm thick and does not show ulceration.

- T1b: The tumour is no more than 1 mm thick and shows ulceration or has a higher mitotic rate (a measure of cell division).

- T2: The tumour is between 1 and 2 mm thick.

- T2a: No ulceration is present.

- T2b: Ulceration is present.

- T3: The tumour is between 2 and 4 mm thick.

- T3a: No ulceration is present.

- T3b: Ulceration is present.

- T4: The tumour is thicker than 4 mm.

- T4a: No ulceration is present.

- T4b: Ulceration is present.

N stages (lymph node stages)

- N0: No cancer is found in nearby lymph nodes, and there are no signs of cancer in nearby skin (called in-transit, satellite, or microsatellite metastases).

- N1: Cancer has spread to one nearby lymph node or nearby skin.

- N1a: Cancer is found in one lymph node during a sentinel lymph node biopsy (a test to check for microscopic disease).

- N1b: Cancer is found in one lymph node during a physical exam or imaging study (clinically detected).

- N1c: No cancer is found in lymph nodes, but cancer is present in nearby skin or soft tissue.

- N2: Cancer has spread to two or three nearby lymph nodes or nearby skin.

- N2a: Two or three lymph nodes are positive for cancer on sentinel lymph node biopsy.

- N2b: Cancer is found in two or three lymph nodes on physical exam or imaging.

- N2c: Cancer is found in one lymph node along with cancer in nearby skin or soft tissue.

- N3: Cancer has spread to four or more lymph nodes or matted (connected) lymph nodes, or there is cancer in nearby skin with two or more lymph nodes involved.

- N3a: Four or more lymph nodes are positive for cancer on sentinel lymph node biopsy.

- N3b: Four or more lymph nodes are clinically detected, or any matted lymph nodes are present.

- N3c: Cancer is found in two or more lymph nodes along with cancer in nearby skin or soft tissue.