By Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

August 31, 2025

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNEC) is a rare and aggressive type of cervical cancer. It develops from small sized cancer cells that exhibit features of neuroendocrine differentiation, meaning they behave like hormone-producing cells typically found in the body. Because it is a high-grade cancer, SCNEC tends to grow quickly and spread early.

This tumor can arise anywhere in the female reproductive tract but is most commonly found in the cervix. When it occurs in the cervix, it is strongly associated with infection by high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV), especially HPV 16 and HPV 18.

What are the symptoms of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma?

The symptoms of SCNEC of the cervix are similar to those of other cervical cancers. They depend on the size of the tumor and whether it has spread beyond the cervix.

Common symptoms include:

-

Abnormal vaginal bleeding, which may occur after sex, between periods, or after menopause.

-

Watery or bloody vaginal discharge.

-

Pelvic pain or discomfort.

-

Pain during or after sexual intercourse.

Because this tumor is aggressive, some people may already have signs of spread, such as pain from involvement of nearby organs or symptoms related to distant metastasis.

Who gets this cancer?

SCNEC of the cervix is very rare. It accounts for less than 1% of all cervical cancers. The average age at diagnosis is about 48 years, but it can occur in both younger and older patients. SCNEC at other sites in the gynecological tract, such as the endometrium or ovary, is even less common and usually presents later in life.

What causes small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix?

Most cases are caused by infection with high-risk HPV, especially types 16 and 18. HPV infects the cells of the cervix and, over time, can change the genetic material of those cells. These changes disrupt normal cell growth and can lead to cancer.

Molecular studies of SCNEC of the cervix have shown alterations in several cancer-related pathways, including MAPK, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and p53. Some tumors show loss of genetic material from the short arm of chromosome 3. These changes may contribute to the aggressive nature of this tumor.

How is the diagnosis made?

The diagnosis is made by removing a tissue sample from the cervix and a pathologist examining it under the microscope. A biopsy, cone biopsy, or tissue removed during surgery can all be used.

What does small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, SCNEC is composed of small sized cells with very little cytoplasm (the body of the cell). The nuclei of the cells are dark (hyperchromatic) and may press against each other, a feature called nuclear molding. Pathologists often see frequent mitotic figures (dividing tumor cells), many dying cells, and large areas of necrosis (dead tumor tissue). The tumor cells may be arranged in sheets, nests, trabeculae (cords), or rosette-like patterns.

Because SCNEC can look similar to other tumors, pathologists often use special tests to confirm the diagnosis.

What other tests are used to confirm the diagnosis?

Pathologists commonly use a technique called immunohistochemistry (IHC). This test uses antibodies to highlight proteins inside tumor cells.

-

Synaptophysin and chromogranin are the most specific markers for neuroendocrine differentiation.

-

CD56 may also be positive but is less specific.

-

Cytokeratins are usually positive, which shows the tumor is epithelial in origin (arising from lining cells).

-

p16 is often strongly positive in cervical SCNEC because of its association with high-risk HPV.

-

Detection of high-risk HPV using molecular tests may also be performed to confirm the cervical origin of the tumor.

These results help distinguish SCNEC from other cancers, including squamous carcinoma and metastatic small cell carcinoma from the lung.

How is the tumor measured and why is depth of invasion important?

Like other cervical cancers, small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is measured in three dimensions: length, width, and depth of invasion. These measurements help determine the pathologic stage and guide treatment.

-

Length is how far the tumor extends from top to bottom on the cervix.

-

Width is how far it spreads across the surface from side to side.

-

Depth of invasion is how deeply the cancer has grown from the surface layer into the supporting connective tissue (the stroma) of the cervix.

Depth of invasion is especially important because SCNEC is known for early spread through blood vessels and lymphatic channels. Even small tumors that have invaded only a few millimeters can already have spread to lymph nodes or distant organs. For this reason, the depth of invasion is carefully measured, but the risk of spread is higher for SCNEC than for other cervical cancers of the same size.

Has the tumor spread outside of the cervix?

SCNEC often spreads beyond the cervix early in its course. The tumor may extend directly into nearby structures such as the endometrium, vagina, parametrium (tissue around the cervix), bladder, or rectum. This type of direct growth is called tumor extension.

The presence of extension outside the cervix increases the stage of the cancer and is associated with a higher risk of recurrence and worse prognosis. Because distant spread is also common, imaging tests are often recommended in addition to the pathology report to check for spread to organs such as the lungs or liver.

What does lymphovascular invasion mean?

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means that cancer cells have entered small blood vessels or lymphatic channels within the cervix. This is a very common finding in SCNEC.

Because lymphovascular invasion provides a pathway for the cancer to spread, its presence greatly increases the risk that tumor cells will be found in lymph nodes or at distant sites. If lymphovascular invasion is described in the report, doctors almost always recommend more aggressive treatment, which may include lymph node removal, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

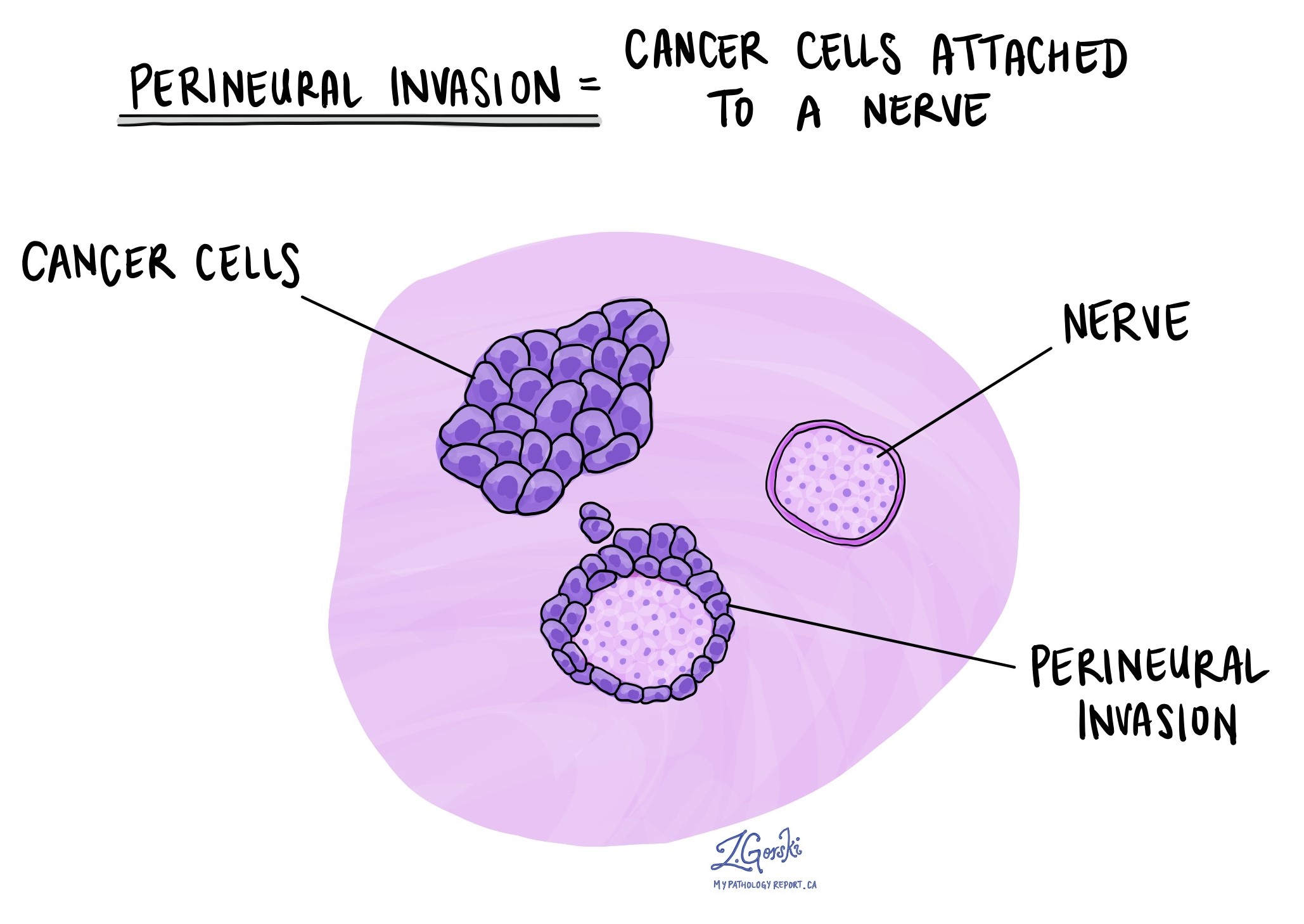

What does perineural invasion mean?

Perineural invasion (PNI) means that cancer cells are growing around or into small nerves in the cervix. Although it is less common than lymphovascular invasion, when present, perineural invasion is considered a sign of more aggressive behavior. It indicates a higher risk of local recurrence and may influence treatment planning.

What are margins and why are they important?

Margins are the cut edges of the tissue removed during surgery. A pathologist carefully examines the margins under the microscope to see whether cancer cells are present at the edge.

-

A negative margin means no cancer cells are found at the edge, suggesting that the tumor was completely removed.

-

A positive margin means cancer cells reach the edge, raising concern that some cancer remains in the body.

Clear margins are important in SCNEC because of its high risk of recurrence. When margins are positive, doctors usually recommend additional treatment such as repeat surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune system organs that filter harmful substances and help the body fight infection. They are also one of the first places cervical cancer can spread. Because SCNEC is aggressive, lymph node involvement is common even when the tumor is small.

During surgery, lymph nodes from the pelvis and sometimes from the para-aortic region (higher up in the abdomen) may be removed and examined under the microscope. The pathology report will describe:

-

How many lymph nodes were removed.

-

The location of the lymph nodes.

-

Whether any contained cancer.

If cancer is present in a lymph node, the size of the cancer deposit is measured:

-

Isolated tumor cells are smaller than 0.2 millimeters.

-

Micrometastasis measures between 0.2 and 2 millimeters.

-

Macrometastasis is larger than 2 millimeters.

A lymph node that contains cancer is described as positive. A node without cancer is described as negative. The number and size of positive nodes are important for staging, treatment planning, and predicting outcome.

How is small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix staged?

Staging describes how far the cancer has spread within the cervix and beyond. For small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, staging is especially important because this tumor is known for early spread to lymph nodes and distant organs. Even small tumors can behave aggressively, so both the tumor stage and the presence of spread are used to guide treatment.

Two systems are commonly used:

-

The TNM system records the tumor size and growth within the cervix (T), whether cancer has spread to lymph nodes (N), and whether there are distant metastases (M).

-

The FIGO system focuses on how far the tumor has extended beyond the cervix into nearby structures, lymph nodes, or distant sites. This system is widely used by gynecologic oncologists to guide treatment planning.

TNM pathologic stage

-

T category (tumor):

-

T1a: The tumor is only visible under the microscope and measures no more than 5 millimeters in depth and no more than 7 millimeters in width.

-

T1b: The tumor is visible or measures deeper than 5 millimeters or wider than 7 millimeters.

-

T2a: The tumor has spread beyond the cervix and uterus but has not invaded the parametrium.

-

T2b: The tumor has spread into the parametrium.

-

T3a: The tumor involves the lower third of the vagina.

-

T3b: The tumor extends to the pelvic wall or blocks a ureter, leading to kidney damage.

-

T4: The tumor has invaded the bladder, rectum, or extended beyond the pelvis.

-

-

N category (lymph nodes):

-

NX: No lymph nodes were removed for examination.

-

N0: No cancer was found in the nodes.

-

N0(i+): Only isolated tumor cells smaller than 0.2 millimeters were present.

-

N1: A larger deposit of cancer was found in at least one node.

-

-

M category (distant spread):

-

M0: No distant spread was found.

-

M1: Cancer has spread to distant organs such as the lungs, liver, or bones.

-

FIGO stage

-

Stage I: The cancer is confined to the cervix.

-

Stage IA1: The depth of invasion is 3 millimeters or less.

-

Stage IA2: The depth of invasion is between 3 and 5 millimeters.

-

Stage IB1: The tumor is 2 centimeters or smaller.

-

Stage IB2: The tumor is more than 2 centimeters but 4 centimeters or smaller.

-

Stage IB3: The tumor is larger than 4 centimeters.

-

-

Stage II: The cancer has spread beyond the cervix but not to the pelvic wall or the lower third of the vagina.

-

Stage IIA1: The tumor involves the upper vagina and is 4 centimeters or smaller.

-

Stage IIA2: The tumor in the upper vagina is larger than 4 centimeters.

-

Stage IIB: The tumor extends into the parametrium.

-

-

Stage III: The cancer has spread more extensively within the pelvis.

-

Stage IIIA: The cancer involves the lower third of the vagina.

-

Stage IIIB: The cancer reaches the pelvic wall or blocks a ureter.

-

Stage IIIC1: Cancer is present in pelvic lymph nodes.

-

Stage IIIC2: Cancer is present in para-aortic lymph nodes.

-

-

Stage IV: The cancer has spread outside the pelvis or to distant sites.

-

Stage IVA: The tumor has grown into the bladder or rectum.

-

Stage IVB: The cancer has spread to distant organs such as the lungs, liver, or bones.

-

Why is staging important for SCNEC?

For SCNEC, staging helps doctors decide on treatment, but stage does not always fully predict behavior because this tumor can spread even when small. Many patients present with advanced disease, and even early-stage tumors have a higher risk of recurrence compared with other types of cervical cancer.

Because of this, treatment for SCNEC often involves a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, even for some patients with apparently early-stage disease.

What is the prognosis for small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix?

The prognosis for SCNEC of the cervix is generally poor compared with other types of cervical cancer. This cancer is considered highly aggressive because it grows quickly, spreads early, and is often diagnosed at an advanced stage. Even small tumors that appear confined to the cervix can spread to lymph nodes or distant organs.

Factors that influence prognosis

-

Stage at diagnosis: The stage of the cancer remains the most important factor. Patients diagnosed at stage I have better outcomes than those diagnosed at later stages, but even stage I tumors carry a higher risk of recurrence than squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Once the cancer has spread to lymph nodes (stage IIIC) or distant organs (stage IVB), long-term survival rates are much lower.

-

Tumor size and depth of invasion: Larger tumors and tumors that invade more deeply into the cervix are more likely to spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body.

-

Lymphovascular invasion: SCNEC frequently shows cancer cells in blood vessels or lymphatic channels. This feature is strongly associated with recurrence and metastasis.

-

Lymph node involvement: The presence of cancer in pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes greatly increases the risk of recurrence and reduces survival.

-

Response to treatment: SCNEC often responds initially to chemotherapy and radiation, but relapses are common. Many recurrences happen within the first two years after diagnosis.

Overall outlook

Published studies show that survival rates for SCNEC are lower than for other cervical cancers at the same stage. While early-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix may have a 5-year survival rate greater than 90%, early-stage SCNEC has much lower survival, and patients frequently relapse even after apparently complete treatment. For advanced stages, survival is often measured in months rather than years.

Treatment considerations

Because of its aggressive nature, SCNEC is usually treated with a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. Fertility-preserving surgery, which may be an option for other cervical cancers, is rarely recommended. Clinical trials and novel treatment approaches may be considered, especially for advanced or recurrent disease.

Importance of follow-up

Close follow-up is essential. Regular visits, imaging, and sometimes blood work are used to monitor for recurrence. Since most relapses happen early, follow-up is usually most frequent in the first two to three years after treatment.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What stage is my tumor and has it spread to lymph nodes or distant organs?

-

Were immunohistochemistry and HPV testing performed to confirm the diagnosis?

-

Did the pathologist see lymphovascular invasion in my tumor?

-

What treatment options are recommended for me?

-

Will my treatment include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination?

-

What is the chance of recurrence and how will follow-up be managed?

-

Are there clinical trials available for this type of cervical cancer?