by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

August 27, 2024

Background:

Adenocarcinoma of the stomach, also known as gastric cancer, is a type of cancer that starts from the cells that cover the inside surface of the stomach. It is the most common form of stomach cancer, accounting for about 90% to 95% of all stomach cancers. The prognosis for adenocarcinoma of the stomach varies widely based on the histologic grade, stage at the time of diagnosis, and the spread of cancer cells to lymph nodes.

The stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many animals. It plays a crucial role in the digestive system by processing ingested food, breaking it down into a semi-liquid form called chyme, and gradually releasing it into the small intestine.

The stomach is divided into four main sections, each with specific functions:

- Cardia: This is the first section where food enters the stomach from the esophagus. It contains glands that secrete mucus, protecting the stomach lining from acidic gastric juice.

- Fundus: Located above the cardia, the fundus stores undigested food and the gases released from the chemical digestion of food. It plays a minor role in the digestion process.

- Body (corpus): The largest section and the main digestive part of the stomach, the corpus secretes acid and digestive enzymes to chemically break down food into a semi-liquid form.

- Pylorus: The final section of the stomach that acts as a valve to control emptying the stomach contents into the small intestine. It contains the pyloric sphincter, which opens to allow chyme to pass into the small intestine and closes to prevent backflow.

The antrum is the most common location for invasive adenocarcinoma of the stomach. This area is particularly susceptible to adenocarcinoma due to its exposure to various factors that can contribute to cancer development, such as Helicobacter pylori infection, chronic inflammation, dietary factors, and the presence of bile acids.

What causes adenocarcinoma in the stomach?

Environmental factors associated with adenocarcinoma in the stomach include Helicobacter pylori infection, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, tobacco smoking, and dietary factors. Genetic mutations involving the genes CDH1 or APC are also associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach.

What are the symptoms of adenocarcinoma of the stomach?

Symptoms of adenocarcinoma of the stomach may include difficulty swallowing, weight loss, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, and feeling full after eating small amounts of food. However, early stages of the disease often produce few or no symptoms, making early detection challenging.

How is the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the stomach made?

The diagnosis is typically made through a combination of imaging studies (like CT or MRI scans), endoscopic procedures, and a biopsy, where a pathologist examines a small tissue sample under a microscope.

Histologic types of adenocarcinoma of the stomach

Adenocarcinoma of the stomach is divided into histologic types based on the way the tumour cells look under the microscope. The most common histologic types are described below.

Tubular adenocarcinoma

Tubular adenocarcinoma is the most common type of adenocarcinoma in the stomach. This type of tumour is made up of abnormal glands that are larger and more irregular than normal stomach glands. Under the microscope, these glands may have a complex or branched appearance. The cancer cells lining the glands look abnormal and often show signs of rapid growth. Tubular adenocarcinomas frequently form in the inner layer of the stomach and can spread into the deeper layers. Pathologists look at the size, shape, and pattern of these glands to determine the diagnosis and assess the tumour grade.

Intestinal type adenocarcinoma

Intestinal-type adenocarcinoma is a type of stomach cancer that resembles the cells found in the intestine. The tumour is made up of well-formed glands that are similar to the glands found in normal intestinal tissue. Intestinal-type adenocarcinoma is often associated with chronic inflammation of the stomach lining, which may be caused by infection with Helicobacter pylori or other risk factors such as smoking or dietary habits. A precancerous change called interstinal metaplasia is often seen in the tissue surrounding the tumour. The behaviour of an intestinal-type adenocarcinoma depends on the histologic grade, which ranges from well differentiated to poorly differentiated. Pathologists look for these well-formed glands and the cells’ intestinal appearance to diagnose intestinal-type adenocarcinoma.

Papillary adenocarcinoma

Papillary adenocarcinoma is a type of adenocarcinoma where the tumour cells form long, finger-like projections called papillae. These papillae are made up of a central core of tissue covered by abnormal cells. This type of adenocarcinoma tends to grow slowly but may invade surrounding tissues if left untreated. Papillary adenocarcinomas are usually more differentiated, meaning the cells resemble normal stomach cells more closely, though they still show abnormal features. The papillary pattern is key to diagnosing this type of adenocarcinoma.

Mucinous adenocarcinoma

Mucinous adenocarcinoma is a type of stomach cancer characterized by the production of large amounts of mucus. The mucus forms pools within the tumour and separates the cancer cells. These tumours often have a gelatinous appearance under the microscope because of the large amounts of mucus. Mucinous adenocarcinomas can be more aggressive than other types of adenocarcinoma, as the mucus can allow the cancer cells to spread more easily through the tissues. Pathologists diagnose mucinous adenocarcinoma by measuring the amount of mucus present in the tumour—if mucus makes up more than 50% of the tumour, it is classified as mucinous.

Diffuse type adenocarcinoma

Diffuse-type gastric cancer is characterized by the scattered distribution of cancer cells across the stomach wall, often including signet ring cells. These cells are known for their distinctive appearance due to a large vacuole displacing the cell’s nucleus. This subtype is less associated with environmental factors and more with genetic predispositions, potentially affecting younger patients and displaying a familial pattern. An alternative name for this type of cancer is poorly cohesive adenocarcinoma.

Diffuse-type adenocarcinoma of the stomach poses significant challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Due to its widespread nature and lack of a well-defined tumour mass, it can be difficult to detect early. It is generally considered more aggressive than the tubular or intestinal types, with a propensity for early metastasis and a poorer response to traditional chemotherapy. Consequently, the prognosis for diffuse-type gastric cancer is often worse, underscoring the importance of identifying this subtype early to tailor the most effective treatment strategies.

Poorly cohesive type adenocarcinoma

Poorly cohesive adenocarcinoma of the stomach is a specific histologic subtype characterized by cancer cells that do not stick together or form solid tumours, instead spreading diffusely throughout the stomach’s lining and wall. This characteristic makes the cancer difficult to detect and diagnose early since the lack of a defined mass means it may not be easily identified through imaging or endoscopy. An alternative name for poorly cohesive type adenocarcinoma is diffuse-type adenocarcinoma.

The poorly cohesive type of adenocarcinoma is characterized by the scattered distribution of cancer cells across the stomach wall, often including signet ring cells. These cells are known for their distinctive appearance due to a large vacuole displacing the cell’s nucleus.

Identifying a poorly discohesive subtype is important for treatment planning and prognosis. Because these cancer cells spread widely and lack intercellular connections, they can penetrate deeper into the stomach wall and metastasize to other organs earlier than more cohesive forms of cancer. This behaviour contributes to a more challenging treatment scenario and generally indicates a poorer prognosis. Recognizing this subtype allows clinicians to consider more aggressive and tailored therapeutic approaches, acknowledging the unique challenges in managing this form of stomach cancer.

Signet ring cells

Signet ring cells are typically found in diffuse or poorly cohesive adenocarcinoma of the stomach. These cells contain large vacuoles of mucin that push the nucleus to the periphery, giving the cell a ring-like appearance. This feature is significant because signet ring cell carcinoma is known for its aggressive behaviour and tendency to spread more diffusely throughout the stomach wall and beyond, compared to other forms of stomach cancer. Signet ring cells are typically seen in poorly cohesive type adenocarcinoma and diffuse-type adenocarcinoma of the stomach.

The identification of signet ring cells is important for several reasons. Firstly, it often suggests a worse prognosis due to the aggressive nature of the cancer and its ability to spread rapidly. Secondly, this finding can influence treatment decisions, as cancers with signet ring cells may respond differently to chemotherapy and other treatments than other types of stomach cancer.

Histologic grade

Invasive adenocarcinoma of the stomach is divided into three grades – well differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated. The grade is based on the percentage of the tumour cells forming round structures called glands. A tumour that does not create any glands is called undifferentiated. The grade is important because poorly differentiated and undifferentiated tumours tend to behave more aggressively. For example, these tumours are more likely to spread to lymph nodes and other body parts.

- Well differentiated: More than 95% of the tumour comprises glands. Pathologists also describe these tumours as grade 1.

- Moderately differentiated: 50 to 95% of the tumour comprises glands. Pathologists also describe these tumours as grade 2.

- Poorly differentiated: Less than 50% of the tumour comprises glands. Pathologists also describe these tumours as grade 3.

- Undifferentiated: Very few glands are seen anywhere in the tumour.

Depth of invasion and pathologic stage (pT)

In pathology, “invasion” refers to the process where cancer cells spread from the tumour’s original site into surrounding tissues or organs. Specifically, in the case of adenocarcinoma, which originates in the stomach’s mucosa (the innermost lining), invasion means the cancer cells have moved into other stomach layers or even to organs outside the stomach. A pathologist can only observe invasion by examining the tumour under a microscope.

During this microscopic examination, the pathologist determines how far the cancer cells have moved beyond the mucosa into nearby tissue, known as the depth or level of invasion. The significance of identifying the depth of invasion lies in its ability to predict the cancer’s aggressiveness: tumours that penetrate deeper into the stomach’s wall are more prone to metastasize to other body parts, including lymph nodes, liver, or lungs. Moreover, the depth of invasion aids in establishing the tumour’s pathologic stage (pT), which is crucial for deciding on the most appropriate treatment strategy.

Most pathology reports for invasive adenocarcinoma of the stomach will describe the depth or level of invasion as follows:

- Intramuscosal: A tumour is called intramucosal if the cancer cells have not spread outside the mucosa, including the lamina propria or muscularis mucosa.

- Submucosal: Submucosal means that the cancer cells have passed the muscularis mucosa and are into the submucosa.

- Muscularis propria: The muscularis propria is the thick bundle of muscle in the middle of the stomach. This level of invasion can usually only be seen after the entire tumour has been removed.

- Subserosal soft tissue: Cancer cells in the subserosal soft tissue are near the outer surface of the stomach.

- Serosa: Cancer cells that pass the serosa on the outside surface of the stomach. From here, cancer cells can spread to nearby organs such as the spleen, pancreas, small intestine, colon, adrenal gland, or kidney.

Your pathologist will use the depth of invasion to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT) as follows:

- T1a: Cancer cells were only found in the mucosa. This is also called intramucosal adenocarcinoma.

- T1b: The cancer cells have spread into the submucosa.

- T2: The cancer cells have spread into the muscularis propria.

- T3: The cancer cells are in the subserosal soft tissue just below the outer surface of the stomach.

- T4a: The cancer cells have gone through the serosa and are on the outer surface of the stomach.

- T4b: The cancer cells have spread into organs near the stomach.

HER2

Cells throughout the body produce the HER2 protein, which acts like a switch to promote cell growth and division. However, when cancer cells overproduce HER2, they grow and divide much faster than normal cells. Approximately one in five stomach tumours overproduce HER2. Therefore, your pathologist will test your cancer cells for HER2 presence.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is the most commonly used test to detect HER2 in cancer cells. Another method is called fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Some labs will perform a FISH test only after the IHC test produces an equivocal result.

If your tumour was tested using immunohistochemistry, your report will categorize the results as:

- Negative (0 or 1) – Indicates the cancer cells are not overproducing HER2.

- Equivocal (2) – Suggests the cancer cells might be overproducing HER2.

- Positive (3) – Confirms the cancer cells are overproducing HER2.

Patients with HER2-positive tumours may qualify for specific treatments. Discuss with your doctor the treatment options that are available to you.

Mismatch repair proteins (MMR)

Mismatch repair (MMR) is a critical system within all normal, healthy cells that corrects DNA errors. This system relies on different proteins, mainly MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2.

These four proteins, MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2, pair up (MSH2 with MSH6 and MLH1 with PMS2) to repair damaged DNA. If a protein is missing, its pair cannot repair DNA effectively, increasing the cancer risk.

Pathologists perform mismatch repair tests on tumour samples to check for the absence of any of these proteins, a process detailed in pathology reports. The primary method for this testing is immunohistochemistry, which identifies whether tumour cells produce all four mismatch repair proteins.

If a protein is absent, the pathology report will note it as “lost” or “deficient.” Often, when one protein is missing, its pair is also lost. If the protein is expressed normally, the pathology report will note it as “intact”.

For stomach adenocarcinoma, the absence of one or more mismatch repair proteins usually signals a better prognosis and indicates potential higher responsiveness to immune checkpoint inhibitors, a cancer treatment.

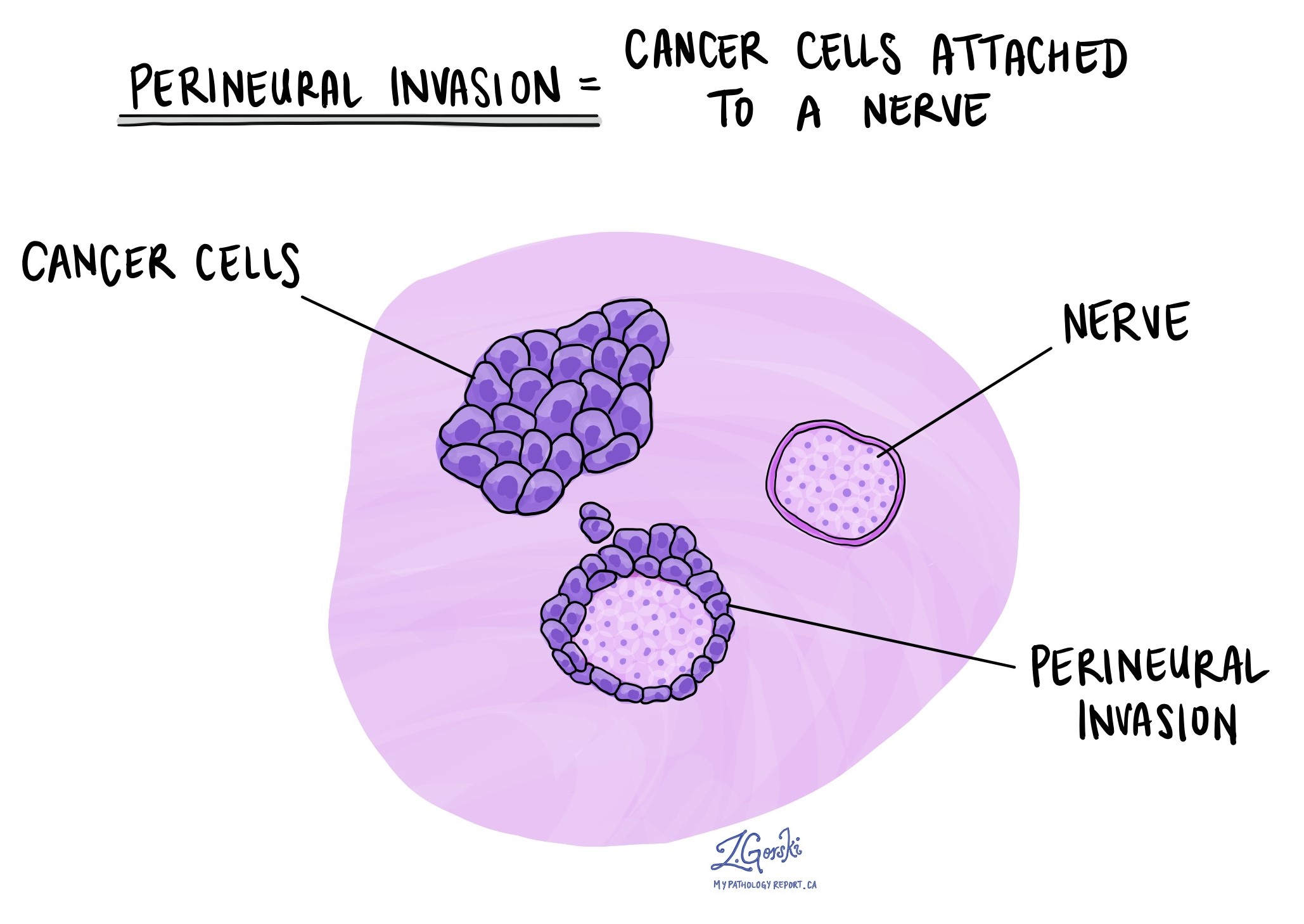

Perineural invasion

Pathologists use the term “perineural invasion” to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that refers explicitly to cancer cells found inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. Perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, unlike lymphatic vessels, which have a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic vessels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it spreads cancer cells to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the liver, via the blood or lymphatic vessels.

Lymph nodes

Small immune organs, known as lymph nodes, are located throughout the body. Cancer cells can travel from a tumour to these lymph nodes via tiny lymphatic vessels. For this reason, doctors often remove and microscopically examine lymph nodes to look for cancer cells. This process, where cancer cells move from the original tumour to another body part, like a lymph node, is termed metastasis.

Cancer cells usually first migrate to lymph nodes near the tumour, although distant lymph nodes may also be affected. Consequently, surgeons typically remove lymph nodes closest to the tumour first. They might remove lymph nodes farther from the tumour if they are enlarged and there’s a strong suspicion they contain cancer cells.

Pathologists will examine any lymph nodes removed under a microscope, and the findings will be detailed in your report. A “positive” result indicates the presence of cancer cells in the lymph node, while a “negative” result means no cancer cells were found. If the report finds cancer cells in a lymph node, it might also specify the size of the largest cluster of these cells, often referred to as a “focus” or “deposit.” Extranodal extension occurs when tumour cells penetrate the lymph node’s outer capsule and spread into the adjacent tissue.

Examining lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, it helps determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, discovering cancer cells in a lymph node suggests an increased risk of later finding cancer cells in other body parts. This information guides your doctor in deciding whether you need additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure like an excision or resection, which removes the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was entirely removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

About this article

Doctors wrote this article to help you read and understand your pathology report. Contact us if you have questions about this article or your pathology report. For a complete introduction to your pathology report, read this article.