by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD FRCPC

September 3, 2025

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is a precancerous condition of the cervix caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). It is composed of squamous cells that have been infected and altered by the virus. These abnormal cells are found in the transformation zone, which is the part of the cervix where glandular cells are gradually replaced by squamous cells.

CIN is called a precancerous disease because over time, and if left untreated, it can progress to cervical cancer, most often HPV associated squamous cell carcinoma. CIN is divided into three levels: CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3. The risk of developing cancer is lowest with CIN1 and highest with CIN3.

Do all HPV infections turn into CIN?

No. Most HPV infections do not turn into CIN. HPV is a very common virus and in most people, the immune system clears the infection within one to two years. Only a small percentage of infections persist in the cervix, and it is these long-lasting infections with high-risk HPV types that can lead to the development of CIN.

How long does it take for an HPV infection to turn into CIN?

If an HPV infection does not clear and persists, it may take several years for CIN to develop. In general, CIN2 and CIN3, the higher-grade lesions, usually appear after a persistent infection that has lasted two years or more. This slow progression is one of the reasons why regular Pap tests and HPV screening are effective at preventing cervical cancer. Screening allows precancerous changes to be found and treated before they turn into cancer.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of CIN is made by examining cells or tissue from the cervix under the microscope. The sample may be collected through:

-

A Pap test, which looks at cells scraped from the cervix.

-

A cervical biopsy, which removes a small piece of tissue.

-

An excision procedure, such as a LEEP or cone biopsy, which removes a larger portion of the cervix.

How do pathologists grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia?

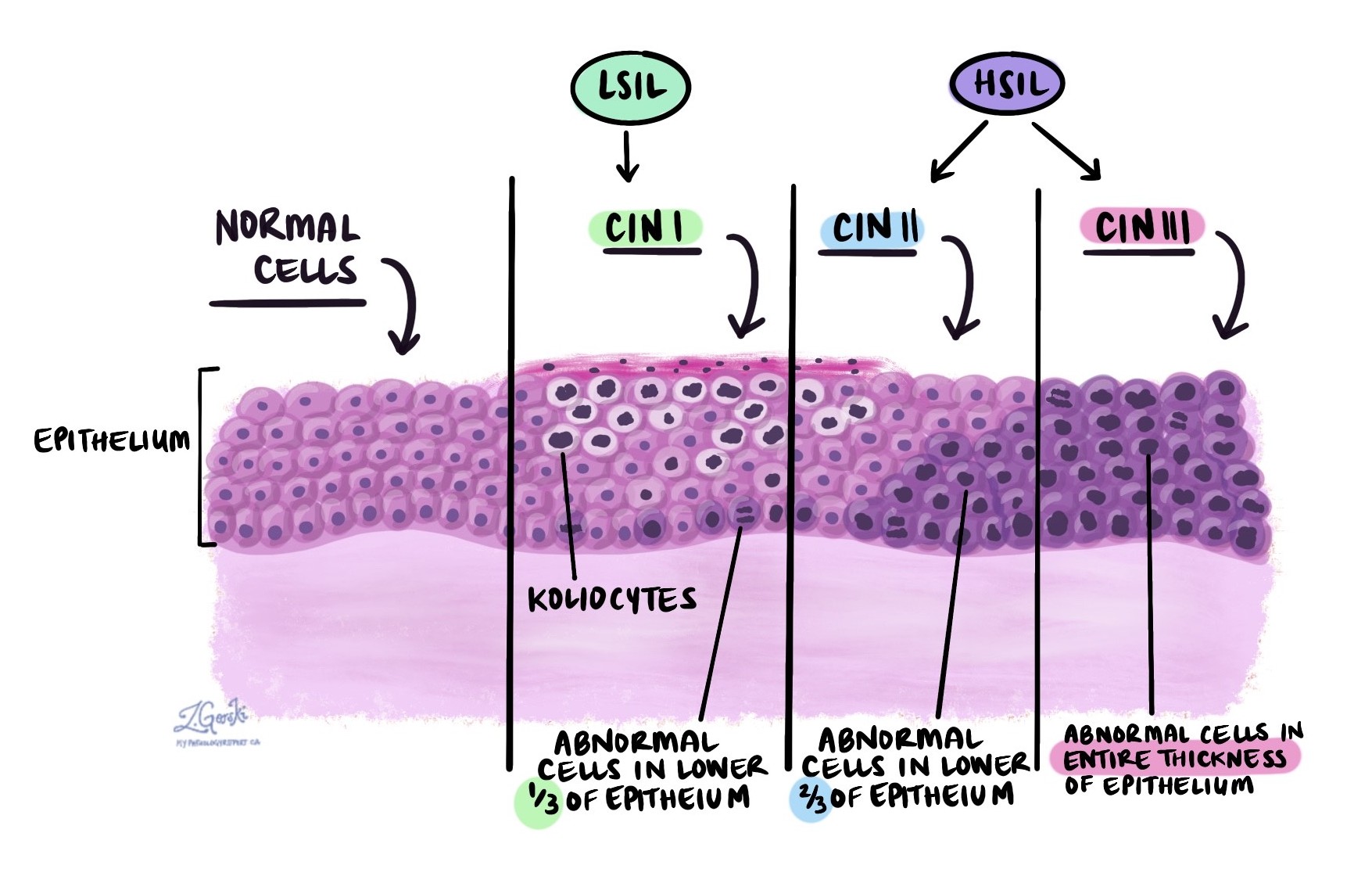

Pathologists divide CIN into three levels based on how much of the epithelium (the surface layer of the cervix) is replaced by abnormal squamous cells. Your pathology report should specify which grade of CIN is present and, for larger tissue samples, whether abnormal cells are present at the margins (see below for more information about margins).

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 (CIN1)

In CIN1, abnormal squamous cells are mostly seen in the lower one-third of the epithelium. A hallmark feature of CIN1 is the presence of koilocytes, which are squamous cells that have been infected by HPV. Koilocytes are larger than normal squamous cells, have irregular dark nuclei, and often show a clear space or “halo” around the nucleus. Some koilocytes have more than one nucleus.

Pathologists may also see an increased number of dividing cells, called mitotic figures.

Another name for CIN1 is low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL). The risk of CIN1 progressing to cancer is low, and in most people, CIN1 resolves over time without treatment.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 (CIN2)

In CIN2, abnormal cells are found in the lower two-thirds of the epithelium. These cells are darker (hyperchromatic), immature, and lack the normal maturation that squamous cells usually show as they move toward the surface.

The abnormal cells have small amounts of cytoplasm compared to their nuclei, making them look darker and less pink than normal cells. Dividing cells are more numerous, and some show abnormal division patterns, called atypical mitotic figures.

Another name for CIN2 is high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). CIN2 carries a higher risk of developing into cancer than CIN1, but the risk is still lower than CIN3.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 (CIN3)

In CIN3, abnormal squamous cells are seen throughout the entire thickness of the epithelium, from the surface to the base. The cells are dark and lack normal maturation. They have less cytoplasm compared to the size of their nuclei.

Many dividing cells are seen, including atypical mitotic figures.

Another name for CIN3 is also high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). CIN3 carries the highest risk of progressing to cancer, and treatment is almost always recommended to remove the abnormal tissue.

What is p16?

Pathologists often perform a special test called immunohistochemistry for p16 when diagnosing CIN. Cells infected with high-risk HPV produce large amounts of the p16 protein. Increased p16 is commonly seen in CIN2 and CIN3.

If p16 is positive (strong and continuous staining), it supports the diagnosis of CIN2 or CIN3 and helps distinguish these lesions from other conditions that can look similar under the microscope. CIN1 is usually negative or only weakly positive for p16.

What is a margin and why are margins important?

A margin is the cut edge of tissue removed during a surgical procedure such as a LEEP or cone biopsy. Pathologists carefully examine the margins under the microscope to determine whether abnormal cells extend to the edge of the specimen.

-

A negative margin means that no CIN is present at the cut edge, suggesting that the lesion has been completely removed.

-

A positive margin means that CIN is present at the cut edge, increasing the risk that abnormal cells remain and the lesion could recur.

Margins are only reported in surgical specimens, not in Pap tests or small biopsies.

Typical cervical margins include:

-

Endocervical margin – This is the inner part of the cervix near the uterus.

-

Ectocervical margin – this is the outer part of the cervix near the vagina.

-

Stromal margin – This is the deeper tissue within the cervix.

What is the risk of CIN turning into cancer?

CIN is considered a precancerous condition because if untreated, it can eventually develop into cervical cancer. However, the risk of progression depends on the grade of CIN.

-

CIN1 has a low risk of turning into cancer and often resolves naturally.

-

CIN2 has a moderate risk of progressing and may be treated, especially if it does not go away with monitoring.

-

CIN3 has a high risk of developing into cervical cancer and is usually treated to remove the abnormal tissue.

With regular Pap tests and HPV screening, CIN is usually detected and treated before it progresses to cancer.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What grade of CIN was found in my biopsy (CIN1, CIN2, or CIN3)?

-

Did my sample test positive for high-risk HPV?

-

Do I need treatment now, or is monitoring an option?

-

Were the margins clear after my procedure?

-

How often will I need follow-up Pap tests or HPV testing?

-

What is my risk of CIN returning or progressing to cancer?