by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD FRCPC

February 4, 2025

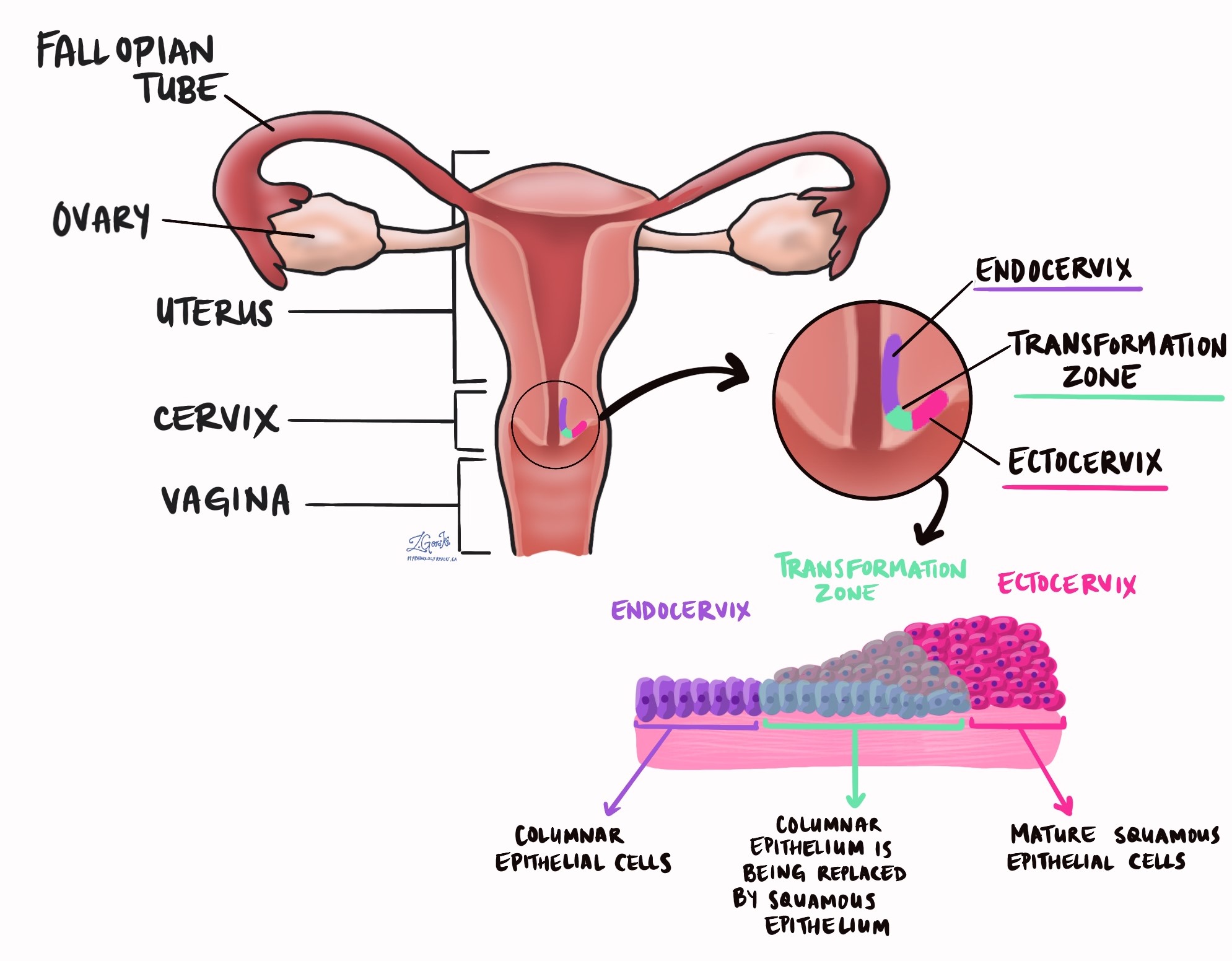

High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) is a precancerous condition of the cervix caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). It is made up of abnormal squamous cells that have been infected and changed by the virus. These cells are found in the transformation zone, a part of the cervix where normal glandular cells are gradually replaced by squamous cells.

Is high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cancer?

HSIL itself is not cancer, but it increases the risk of developing a type of cervical cancer called HPV associated squamous cell carcinoma. Because of this, treatment is usually recommended to remove the affected area of the cervix. Another name for HSIL is cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), specifically CIN2 or CIN3.

What is the difference between high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion and low grade intraepithelial lesion?

HSIL and low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) are both precancerous conditions caused by HPV. However, LSIL has a much lower risk of turning into cancer and often goes away on its own without treatment.

What are the symptoms of high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion?

Many people with HSIL do not have any symptoms, which is why regular Pap tests and HPV screening are important for early detection. However, in some cases, HSIL can cause symptoms such as:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, especially after sex or between periods.

- Unusual vaginal discharge, which may be watery or blood-tinged.

- Pelvic pain or discomfort (less common).

Because HSIL does not usually cause noticeable symptoms, most cases are detected through routine cervical cancer screening.

What causes high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion?

HSIL is caused by a persistent infection with high-risk HPV. HPV is a very common virus that spreads through skin-to-skin contact, including sexual contact. While most HPV infections clear on their own, in some cases, the virus stays in the body and leads to abnormal cell changes in the cervix.

There are many different types of HPV, but most cases of HSIL are caused by high-risk HPV types, particularly HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 51, and others. These high-risk HPV types increase the chance of developing cervical cancer over time.

Not everyone who gets HPV will develop HSIL. The immune system usually fights off the infection within a couple of years. However, in some people, HPV remains in the cervix and leads to precancerous changes.

The risk factors for developing HSIL include:

- Having an HPV infection, especially high-risk types like HPV 16 and 18.

- A weakened immune system, which makes it harder to clear the virus.

- Smoking, which increases the risk of cervical cell changes.

- Long-term use of birth control pills (more than five years).

- Having multiple sexual partners, which increases the chance of exposure to HPV.

- Lack of regular cervical screening, which allows HSIL to go undetected.

How is the diagnosis of high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion made?

HSIL is usually first detected through a Pap test (Pap smear), a screening test that checks for abnormal squamous cells in the cervix. If HSIL is suspected, further tests may be needed to confirm the diagnosis:

- HPV testing: A test that checks for the presence of high-risk HPV types in cervical cells.

- Colposcopy: A procedure where a doctor examines the cervix using a special magnifying device.

- Cervical biopsy: A small sample of tissue is taken from the cervix during a colposcopy to confirm the diagnosis and rule out cervical cancer.

- Endocervical curettage: A sample of cells is taken from the endocervical canal (the inner part of the cervix) to check for abnormal cells that may not be visible.

If a biopsy confirms HSIL, treatment is usually recommended to remove the abnormal cells before they can turn into cancer.

What other tests may be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

Other tests, in addition to Pap testing, colposcopy, and biopsy, may be performed to confirm HSIL and rule out similar conditions.

One of these tests is in situ hybridization for high-risk HPV. This test detects HPV DNA or RNA directly in the tissue sample. It helps confirm that the abnormal cells are caused by high-risk HPV and can distinguish between different HPV types. There are two types of in situ hybridization tests:

- Chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH): A special stain highlights HPV DNA in the cells. The results appear as a color change under the microscope.

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH): Fluorescence dyes detect HPV genetic material, which can be seen under a special microscope.

The possible results of in situ hybridization include:

- Positive for high-risk HPV: Confirms the presence of high-risk HPV types, supporting the diagnosis of HSIL.

- Negative for high-risk HPV: Suggests that another condition may be causing the abnormal cell changes.

What does high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion look like under the microscope?

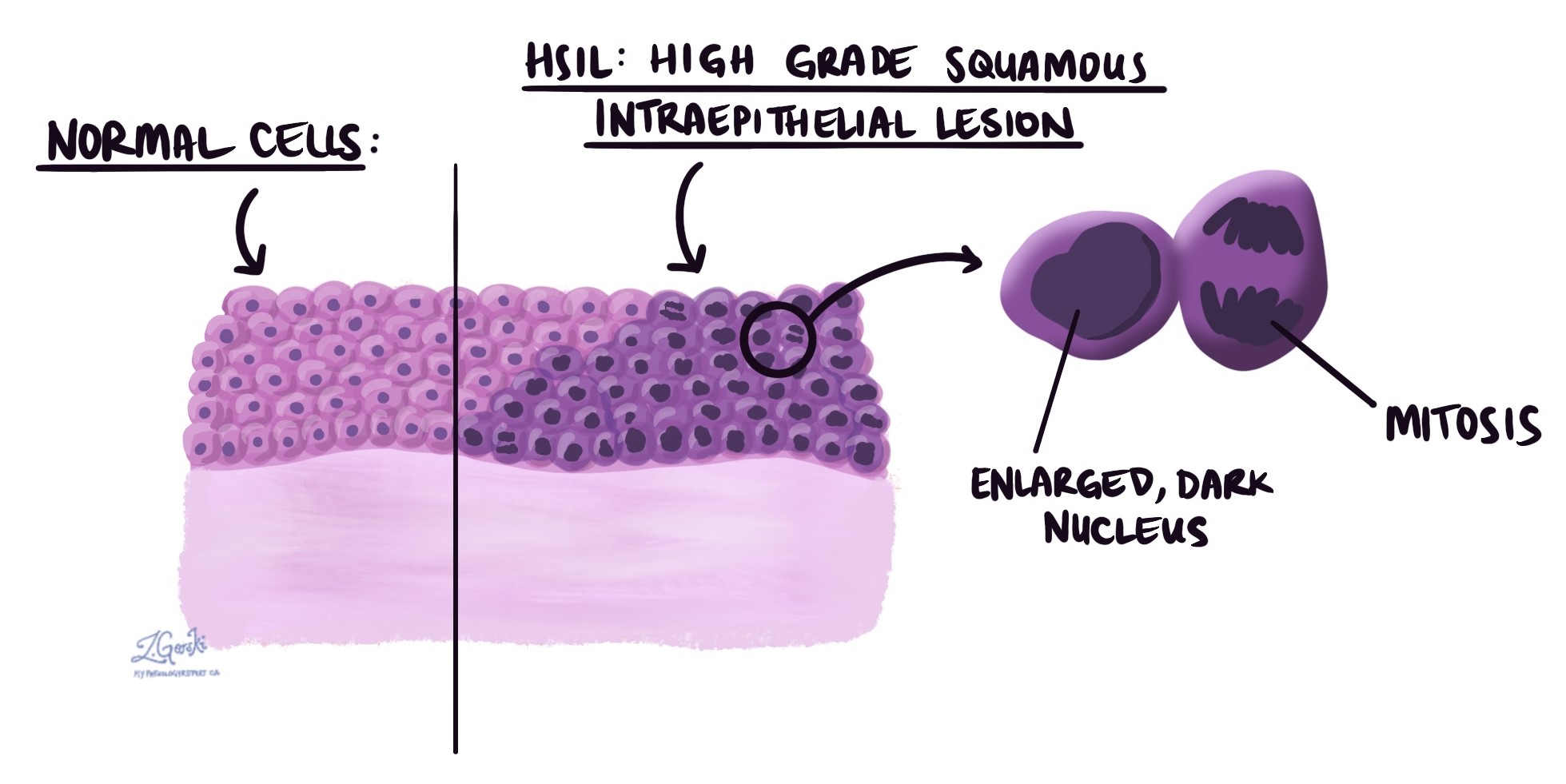

When examined under the microscope, HSIL consists of abnormal squamous cells that are hyperchromatic (darker) and larger than normal squamous cells. The abnormal cells are limited to the epithelium, the thin layer of tissue covering the cervix.

Pathologists often see cells undergoing mitosis, which means they are actively dividing. These rapidly growing cells are a sign of precancerous changes.

Pathologists may perform a special test called immunohistochemistry for p16 to confirm the diagnosis. This test helps distinguish HSIL from other conditions that can look similar under the microscope. When p16 is positive, it strongly supports the diagnosis of HSIL.

What is the treatment for high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion?

Because HSIL increases the risk of cervical cancer, treatment is usually recommended. The goal of treatment is to remove the abnormal cells before they turn into cancer.

Common treatment options include:

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) – A thin wire loop carrying an electrical current is used to remove the abnormal area of the cervix.

- Cold knife cone biopsy (conization) – A larger cone-shaped section of the cervix is surgically removed, often under general anesthesia.

- Cryotherapy – The abnormal cells are frozen and destroyed.

- Laser therapy – A high-energy laser is used to remove or destroy abnormal tissue.

The choice of treatment depends on factors such as age, the extent of HSIL, and whether the patient wishes to have children in the future. After treatment, follow-up Pap tests and HPV testing are needed to ensure that HSIL does not return.

What happens after high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion is diagnosed on a Pap test?

If HSIL is found on a Pap test, your doctor will refer you to a specialist for a colposcopy. This procedure allows the doctor to see the cervix more clearly and, if necessary, take a biopsy.

If the biopsy confirms HSIL, treatment options will be discussed. Sometimes, if the affected area is small, your doctor may recommend careful monitoring instead of immediate treatment.

It is important to attend all follow-up visits because untreated HSIL can progress to cervical cancer over time.

What is a margin, and why are margins important?

A margin is the edge of the tissue that is removed during surgery. Pathologists examine the margins closely to ensure no abnormal cells are left behind.

- A negative margin means that the edges of the removed tissue do not contain HSIL, which is a good result.

- A positive margin means that HSIL is still present at the edge of the tissue, increasing the risk that HSIL could return.

Margins are only described in procedures like LEEP and cone biopsy. Pap smears and small biopsies do not have margins.

The type of margin described depends on which part of the cervix was removed:

- Endocervical margin – The inner part of the cervix near the uterus.

- Ectocervical margin – The outer part of the cervix near the vagina.

- Stromal margin – The deeper tissue inside the cervix.

If HSIL is found at the margin, your doctor may recommend further treatment or close monitoring to remove all abnormal tissues.