by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

November 20, 2024

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a rare type of skin cancer. It starts in the connective tissue, which is the tissue that provides support and structure to the skin. DFSP usually appears as a slow-growing bump on the skin that can feel firm. It most often develops on the trunk, arms, or legs but can occur anywhere on the body. Although DFSP grows slowly and rarely spreads to other body parts, it can grow deeply into the surrounding tissues if left untreated.

What are the symptoms of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans?

The main symptom of DFSP is a lump on the skin. At first, the lump may look like a bruise or scar and feel smooth or rubbery. Over time, it may grow larger and become raised above the skin’s surface. In some cases, the tumour may develop into multiple nodules or a protuberant (bumpy) mass. DFSP is usually not painful, but some people may notice tenderness or itching in the affected area.

What causes dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans?

The exact cause of DFSP is not fully understood. However, it is linked to changes in specific genes that occur in the cells of the tumour. These genetic changes are not inherited and develop during a person’s lifetime. Certain factors, such as previous injury to the skin, may increase the risk of developing DFSP, but in most cases, no clear cause can be identified.

Is dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans benign or malignant?

DFSP is a malignant tumour, which means it is a type of cancer. Unlike benign tumours, malignant tumours have the potential to invade and damage surrounding tissues. However, DFSP rarely metastasises (spreads) to distant parts of the body. This makes it less aggressive than many other cancers. Early detection and complete removal of the tumour are key to preventing further complications.

What genetic changes are found in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans?

Most cases of DFSP are caused by a specific genetic change known as a translocation. This translocation occurs when two different chromosomes, chromosome 17 and chromosome 22, break and exchange pieces. This exchange creates a fusion of two genes called COL1A1 and PDGFB. The fusion gene leads to the overproduction of a protein that stimulates tumour growth. This genetic change is found in more than 90% of DFSP cases and helps confirm the diagnosis.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of DFSP begins with a physical examination and a biopsy. A biopsy is a procedure in which a small piece of the lump is removed and examined under a microscope. Pathologists, who are doctors trained to study tissue samples, look for specific features of DFSP in the biopsy. Special genetic tests, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or next-generation sequencing (NGS), can be performed to detect the COL1A1-PDGFB fusion gene, helping confirm the diagnosis.

Microscopic features of this tumour

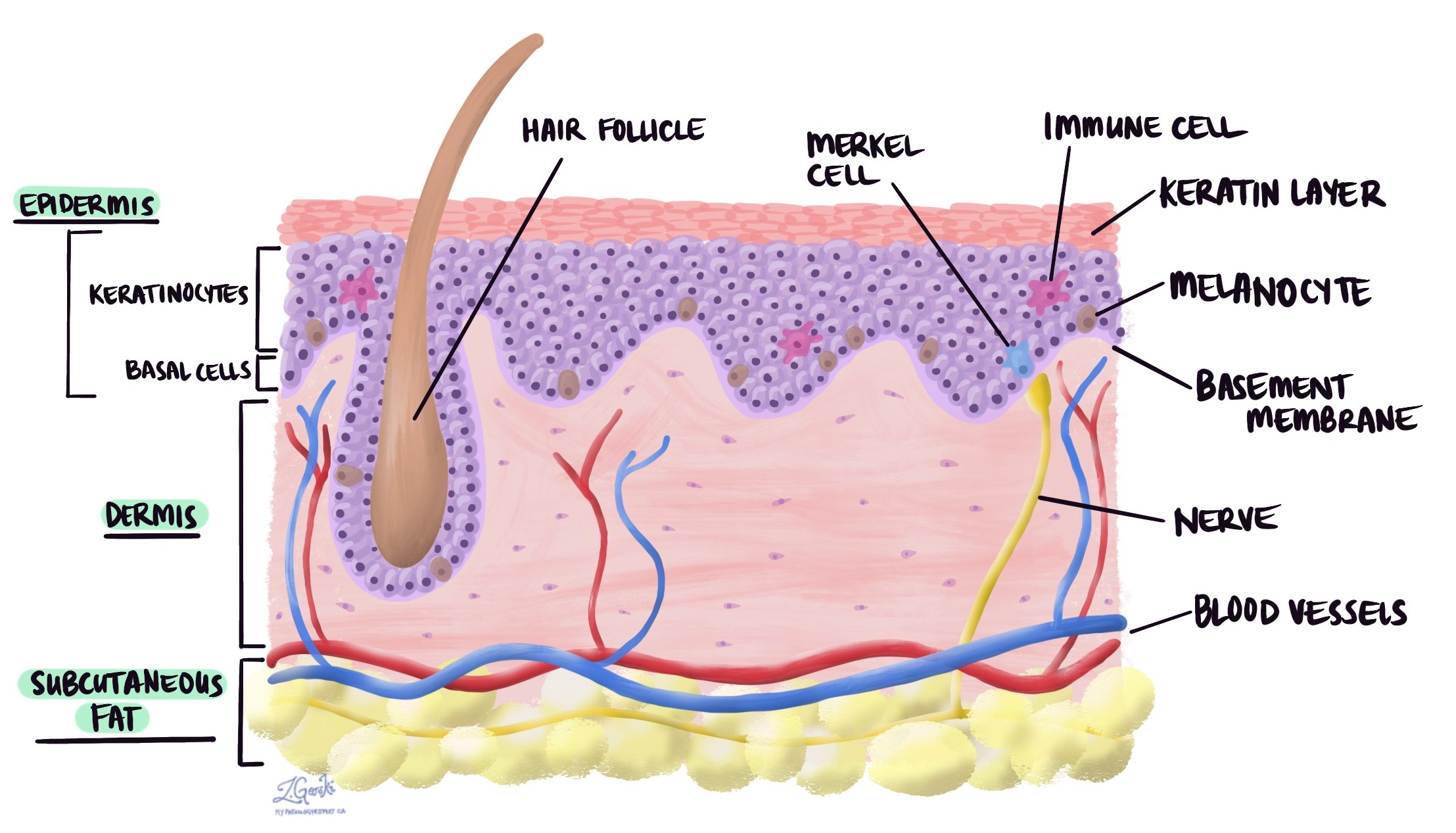

Under the microscope, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is made up of spindle-shaped cells that are long and narrow. These cells are uniform in size and arranged in a storiform or cartwheel-like pattern. The tumour is located primarily in the dermis, the second layer of the skin. Unlike some other skin tumours, DFSP is separated from the top layer of the skin, called the epidermis, by a clear zone called a grenz zone.

As the tumour grows, it often extends into the fat beneath the skin in a distinctive lace-like or honeycomb pattern. The edges of the tumour are poorly defined and may spread in a tentacle-like fashion along tissue planes and around fat lobules. While it is most commonly centred in the dermis, in some cases, it may primarily involve the fat beneath the skin with little or no involvement of the dermis.

The tumour typically shows very few mitotic figures, which are markers of cell division, and there is minimal atypia, meaning the cells look relatively normal. A key feature of DFSP is that it strongly stains for a protein called CD34, identified through special immunohistochemistry tests. This staining helps pathologists distinguish DFSP from other types of tumours.

Histologic subtypes of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) exhibits various histologic subtypes, each characterized by distinct features that differentiate them from the classic form of DFSP. The most common subtypes are described below.

Giant cell fibroblastoma

This subtype is most often seen in children and is considered a pediatric form of DFSP. It shares the same basic features as the classic subtype but also contains large multinucleated cells, called giant cells, with nuclei arranged in a circular or “wreath-like” pattern. These cells often surround spaces that resemble small blood vessels. The tumour also has areas with a jelly-like appearance, known as myxoid change.

Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Myxoid DFSP is a rare subtype where more than half of the tumour consists of a pale, jelly-like material called myxoid stroma. The tumour has a nodular growth pattern and contains many thin, branching blood vessels and scattered immune cells called mast cells. The typical swirling (storiform) pattern of classic DFSP may be less obvious, making diagnosis more challenging.

Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

This subtype contains cells with melanin, the pigment that gives skin its colour. These pigmented cells are often dendritic, meaning they have branching projections. Special tests show that these cells may stain positive for a protein called S100, which helps identify them.

Myoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Myoid DFSP consists of pale nodules made up of spindle-shaped cells with pink cytoplasm, the substance surrounding the cell’s nucleus. These nodules are usually centred around blood vessels and are surrounded by hardened tissue, a feature called stromal hyalinization. Unlike classic DFSP, this subtype does not stain for CD34 but shows positive staining for SMA, a marker found in muscle-like cells.

Plaque-like dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

This subtype appears as a poorly defined tumour in the dermis, with spindle-shaped cells arranged in a wavy or bundled (fascicular) pattern. The tumour often has a myxoid background. It can resemble other skin tumours and requires careful examination to confirm the diagnosis.

Fibrosarcomatous transformation in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

In about 10% of cases, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) undergoes a change called fibrosarcomatous transformation. This means the tumour develops areas that look and behave more aggressively than the classic form. Under the microscope, these transformed areas often show a herringbone or fascicular (bundle-like) growth pattern, with increased cellularity (more cells), more atypia (abnormal-looking cells), and more frequent mitotic activity (cell division).

Fibrosarcomatous areas may appear as distinct nodules within the classic DFSP or develop in a tumour that has recurred after treatment. In these areas, the tumour may lose its typical staining for CD34, a protein commonly seen in DFSP cells. This loss of CD34 staining helps pathologists identify the transformation. In rare cases, the tumour cells in fibrosarcomatous areas may show even more unusual shapes, such as round or pleomorphic (varying in size and shape) cells.

Fibrosarcomatous transformation is significant because it is associated with a worse prognosis. Tumours with this transformation are more likely to recur and may have a higher risk of metastasizing (spreading) compared to classic DFSP. Because of this, close monitoring and more aggressive treatment, such as wider surgical removal or additional therapies, may be recommended.

Margins

Margins refer to the edges of the tissue removed during surgery to treat a tumour, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). After the tumour is surgically removed, the tissue is sent to a pathologist, who examines the margins under a microscope to determine whether there are any tumour cells at the edge of the specimen. This is an important part of the pathology report because it provides information about whether the tumour was removed entirely.

If the margins are “clear” or “negative,” it means there are no tumour cells at the edges, suggesting the tumour has been entirely removed. If the margins are “positive,” it means tumour cells are present at the edges, indicating that some of the tumour may remain in the body. Positive margins may require additional treatment, such as further surgery or other therapies, to remove the tumour completely.

In DFSP, margins are especially important because this tumour tends to grow in a way that extends beyond its visible edges. DFSP can infiltrate surrounding tissues in a lace-like or tentacle-like pattern, making it challenging to ensure complete removal. Wide surgical margins or specialised surgical techniques, like Mohs micrographic surgery, are often recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence and remove all tumour cells. The pathologist’s careful examination of the margins is key to planning any additional treatment and improving the long-term outcome for the patient.

What is the prognosis for someone diagnosed with dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans?

The prognosis for DFSP is generally very good, especially when diagnosed and treated early. The primary treatment is surgery to remove the tumour completely. In most cases, a particular type of surgery called Mohs micrographic surgery is used to ensure all the cancer cells are removed while sparing as much healthy tissue as possible. Although DFSP rarely spreads to other body parts, it can come back (recur) if not entirely removed. Regular follow-up with your doctor is important to monitor for recurrence. With appropriate treatment, most people with DFSP have an excellent long-term outcome.