by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

February 24, 2025

HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma is a rare type of cancer that develops in the nasal cavity or the sinuses. It is linked to infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), a virus that can cause changes in cells and lead to tumour growth. This type of cancer is called “multiphenotypic” because it contains different types of cells, some resembling those found in salivary gland tumours.

What are the symptoms of HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma?

The symptoms of HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma depend on its size and location.

Common symptoms include:

- Nasal congestion or obstruction.

- Nosebleeds.

- Facial pain or pressure.

- Decreased sense of smell.

- Swelling in the face or around the nose.

- Frequent sinus infections that do not improve with treatment.

What causes HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma?

HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma is caused by infection with high-risk HPV. The virus can enter cells and change their growth, leading to uncontrolled cell division and tumour formation. Other risk factors may include exposure to environmental irritants, but HPV is the primary known cause.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis is made by examining a sample of tissue under the microscope. This sample is usually obtained through a biopsy, where a small piece of the tumour is removed for testing. Pathologists look for specific features that indicate this type of cancer and may use additional tests to confirm the diagnosis.

What does HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, this type of cancer often appears as groups of small, round, or oval-shaped cells. These cells may be arranged in various patterns, including solid sheets or circular clusters. Some tumour cells look like those found in the salivary glands, with a mix of two main cell types: ductal cells that form ducts or tubules and myoepithelial cells that provide structural support. The tumour can also show areas where the cells change in shape, becoming more elongated or clear. In some cases, the tumour cells may look like those found in squamous cell carcinoma, a different type of cancer that produces keratin, a tough protein found in skin and nails. The tumour often has many mitotic figures (actively dividing cells), and areas of necrosis (dead cells) may be present. It is common for the tumour to grow into nearby bone, but it usually does not invade nerves or blood vessels.

What other tests may be ordered to confirm the diagnosis?

To confirm the diagnosis of HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma, pathologists may perform additional tests such as immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): This test uses special stains to detect proteins made by the tumour cells. In HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma, IHC can show both ductal and myoepithelial differentiation. Myoepithelial markers include p40, p63, SMA, and calponin, while ductal markers include KIT (CD117). S100 and SOX10 are markers that can be seen in both types of cells. The tumour cells uniformly and strongly express p16, a surrogate marker for HPV.

- In situ hybridization (ISH): Another important test is HPV RNA in situ hybridization, which detects high-risk HPV. While HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma is positive for p16 and high-risk HPV, p16 immunohistochemistry alone is not a reliable indicator of HPV infection in this type of tumour.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, unlike lymphatic vessels, which carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic vessels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it spreads cancer cells to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the liver, via the blood or lymphatic vessels.

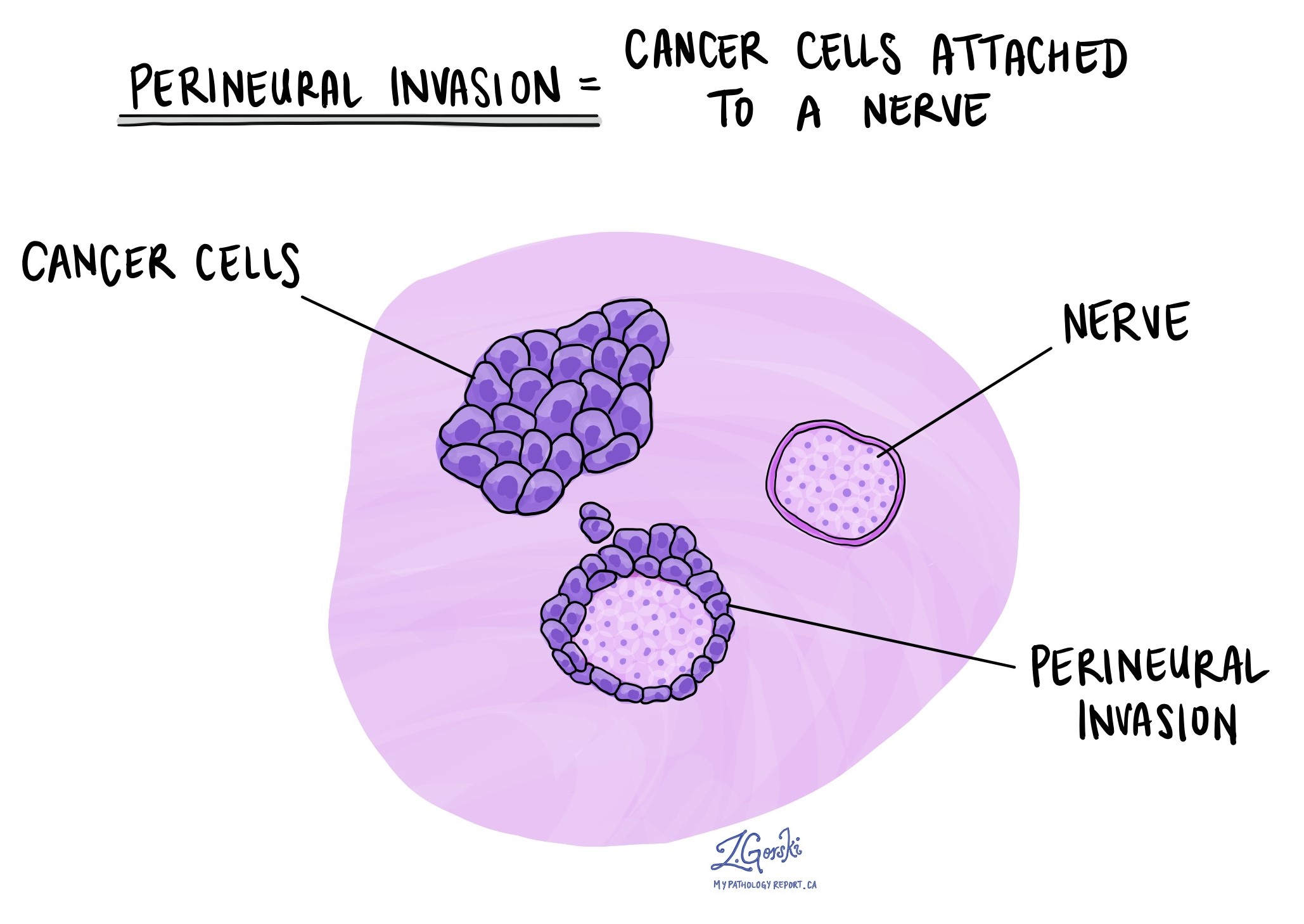

Perineural invasion

Pathologists use the term “perineural invasion” to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that specifically refers to cancer cells inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. Perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure, like an excision or resection, that removes the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was entirely removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs located throughout the body. Cancer cells can travel from a tumour to these lymph nodes via tiny lymphatic vessels. For this reason, doctors often remove and microscopically examine lymph nodes to look for cancer cells. This process, where cancer cells move from the original tumour to another body part, like a lymph node, is termed metastasis.

Cancer cells usually first migrate to lymph nodes near the tumour, although distant lymph nodes may also be affected. Consequently, surgeons typically remove lymph nodes closest to the tumour first. They might remove lymph nodes farther from the tumour if they are enlarged and there’s a strong suspicion they contain cancer cells.

Pathologists will examine any lymph nodes removed under a microscope, and the findings will be detailed in your report. A “positive” result indicates the presence of cancer cells in the lymph node, while a “negative” result means no cancer cells were found. If the report finds cancer cells in a lymph node, it might also specify the size of the largest cluster of these cells, often referred to as a “focus” or “deposit.” Extranodal extension occurs when tumour cells penetrate the lymph node’s outer capsule and spread into the adjacent tissue.

Examining lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, it helps determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, discovering cancer cells in a lymph node suggests an increased risk of later finding cancer cells in other body parts. This information guides your doctor in deciding whether you need additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy.

Pathologic stage

Staging describes the amount and location of cancer in the body. For HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma, the staging system helps determine the size and extent of the tumour (T stage) and whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes (N stage). This information guides treatment and helps predict outcomes.

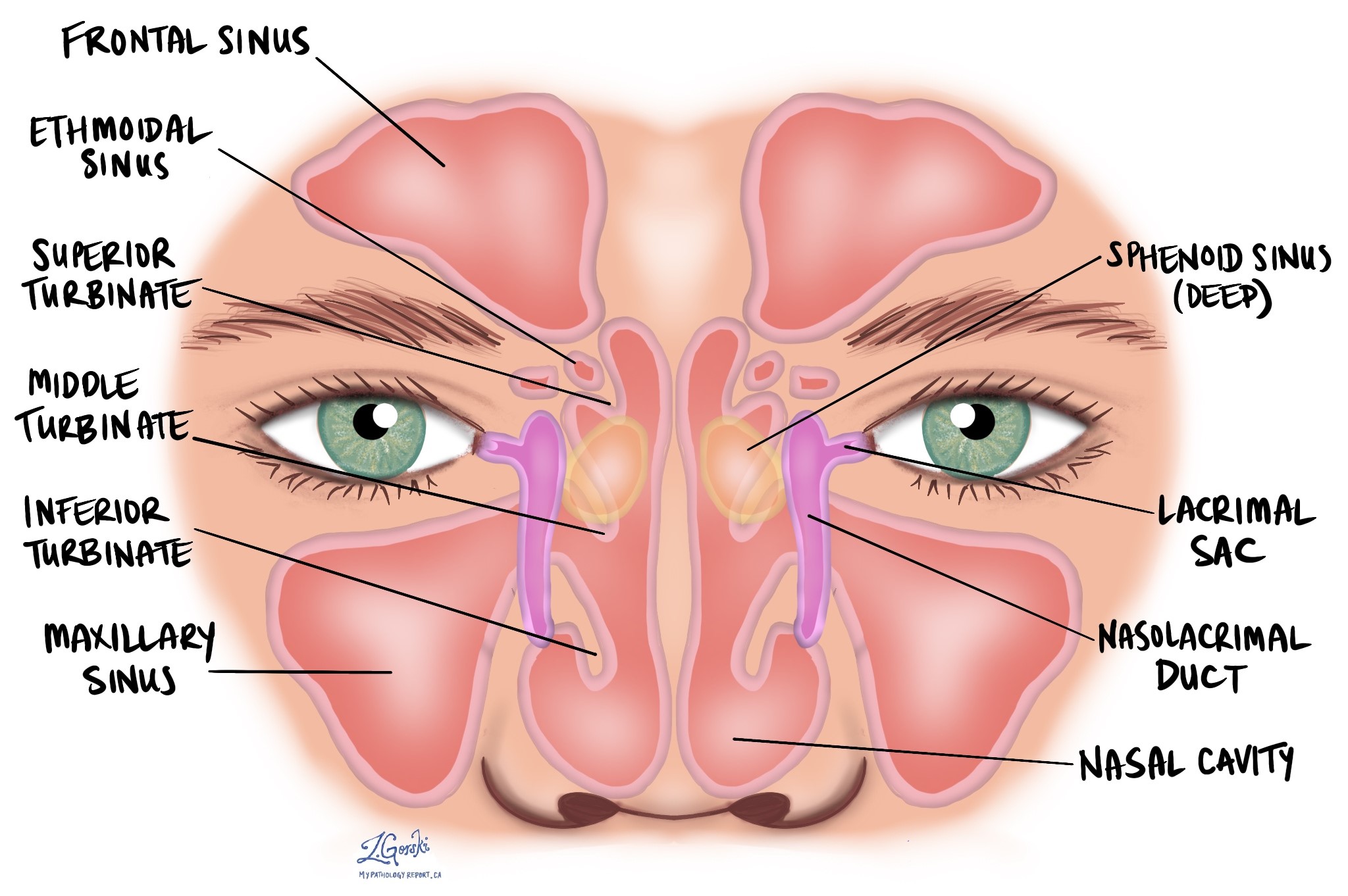

The tumour stage (T stage) depends on where the tumour started—whether in the maxillary sinus, nasal cavity, or ethmoid sinus—as different structures and patterns of spread are associated with each location. Each site has its own staging criteria, reflecting the unique anatomy of these regions.

T stages (tumour stages)

Maxillary sinus

- Tis: The cancer is “in situ,” meaning it is confined to the surface layer and has not invaded deeper tissues.

- T1: The tumour is limited to the lining (mucosa) of the maxillary sinus and has not caused bone damage.

- T2: The tumour has caused bone damage or extends to nearby areas, such as the hard palate or middle nasal passage, but not the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus or pterygoid plates.

- T3: The tumour invades deeper areas, such as the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, soft tissues, floor or medial wall of the eye socket (orbit), pterygoid fossa, or ethmoid sinuses.

- T4: Advanced disease, divided into:

- T4a: Moderately advanced, involving areas like the front part of the eye socket, cheek skin, or other nearby bones (cribriform plate, frontal or sphenoid sinuses).

- T4b: Very advanced, involving critical areas like the brain, cranial nerves, or skull base.

Nasal cavity and ethmoid sinus

- Tis: Cancer is “in situ,” confined to the surface layer.

- T1: The tumour is limited to one area of the nasal cavity or ethmoid sinus, with or without bone involvement.

- T2: The tumour affects two regions within the nasal cavity or ethmoid sinus or extends to adjacent areas, with or without bone involvement.

- T3: The tumour invades critical structures like the floor or medial wall of the orbit, maxillary sinus, palate, or cribriform plate.

- T4: Advanced disease, divided into:

- T4a: Moderately advanced, involving the front of the eye socket, cheek skin, minimal extension into the skull base, or nearby bones.

- T4b: Very advanced, involving the brain, cranial nerves, or deep areas of the skull.

N stages (lymph node stages)

- N0: No cancer is found in nearby lymph nodes.

- N1: Cancer is present in one lymph node on the same side of the neck, and the node is 3 cm or smaller in size without signs of spread outside the node (ENE-negative).

- N2: Cancer has spread to one or more lymph nodes, but none larger than 6 cm. It is divided into:

- N2a: A single lymph node, either 3 cm or smaller with signs of spread outside the node (ENE-positive), or larger than 3 cm but not larger than 6 cm without spread outside the node.

- N2b: Cancer in multiple lymph nodes on the same side of the neck, none larger than 6 cm, and ENE-negative.

- N2c: Cancer in lymph nodes on both sides of the neck or opposite the tumour, none larger than 6 cm, and ENE-negative.

- N3: More advanced lymph node involvement, including:

- N3a: A lymph node larger than 6 cm without spread outside the node.

- N3b: Any lymph node with spread outside the node (ENE-positive), or multiple affected lymph nodes with ENE.

What is the prognosis for a person diagnosed with HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma?

Even though this tumour looks aggressive under the microscope, it tends to behave less aggressively than other high grade carcinomas. Most patients experience local recurrences, meaning the tumour can grow back in the same area after treatment. This happens in about one-third of cases, and sometimes the recurrence occurs years later. However, it is very rare for the tumour to spread to other parts of the body (distant metastases occur in only about 5% of cases). It is also uncommon for this cancer to spread to lymph nodes or cause death related to the tumour. With proper treatment and monitoring, most patients do well.