by Catherine Forse MD FRCPC

March 28, 2022

What is microscopic colitis?

Microscopic colitis is a non-cancerous condition caused by an increased number of immune cells within the mucosa that covers the inside of the colon. This leads to inflammation and damage which prevents the colon from functioning normally. There are two types of microscopic colitis: lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis.

What are the symptoms of microscopic colitis?

People with microscopic colitis can develop watery diarrhea that can last from weeks to years. Other possible symptoms can include abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue.

What causes microscopic colitis?

Doctors still do not know what causes a person to develop microscopic colitis in the first place. However, one theory suggests that it may be an autoimmune condition where immune cells start to attack the cells in the colon. Another theory suggests that the condition may be a reaction to material in fecal matter.

How do pathologists make the diagnosis of microscopic colitis?

If your doctor suspects microscopic colitis based on your symptoms, they will perform a colonoscopy. A colonoscopy is a procedure where a small camera is used to see the inside of your colon. During this procedure, your doctor will take tissue samples called biopsies. Because microscopic colitis can happen in one part of the colon but not another, they will likely take multiple biopsies from the entire length of the colon. Your pathologist will then examine these biopsies under a microscope to determine whether microscopic colitis is present.

For most people with microscopic colitis, their colon will look entirely normal during the colonoscopy. That is because microscopic colitis is a ‘microscopic’ disease, and its features can only be seen when the tissue is examined under a microscope.

What are the types of microscopic colitis?

Pathologists divide microscopic colitis into two types – lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis – based on the features seen after the tissue sample is examined under the microscope.

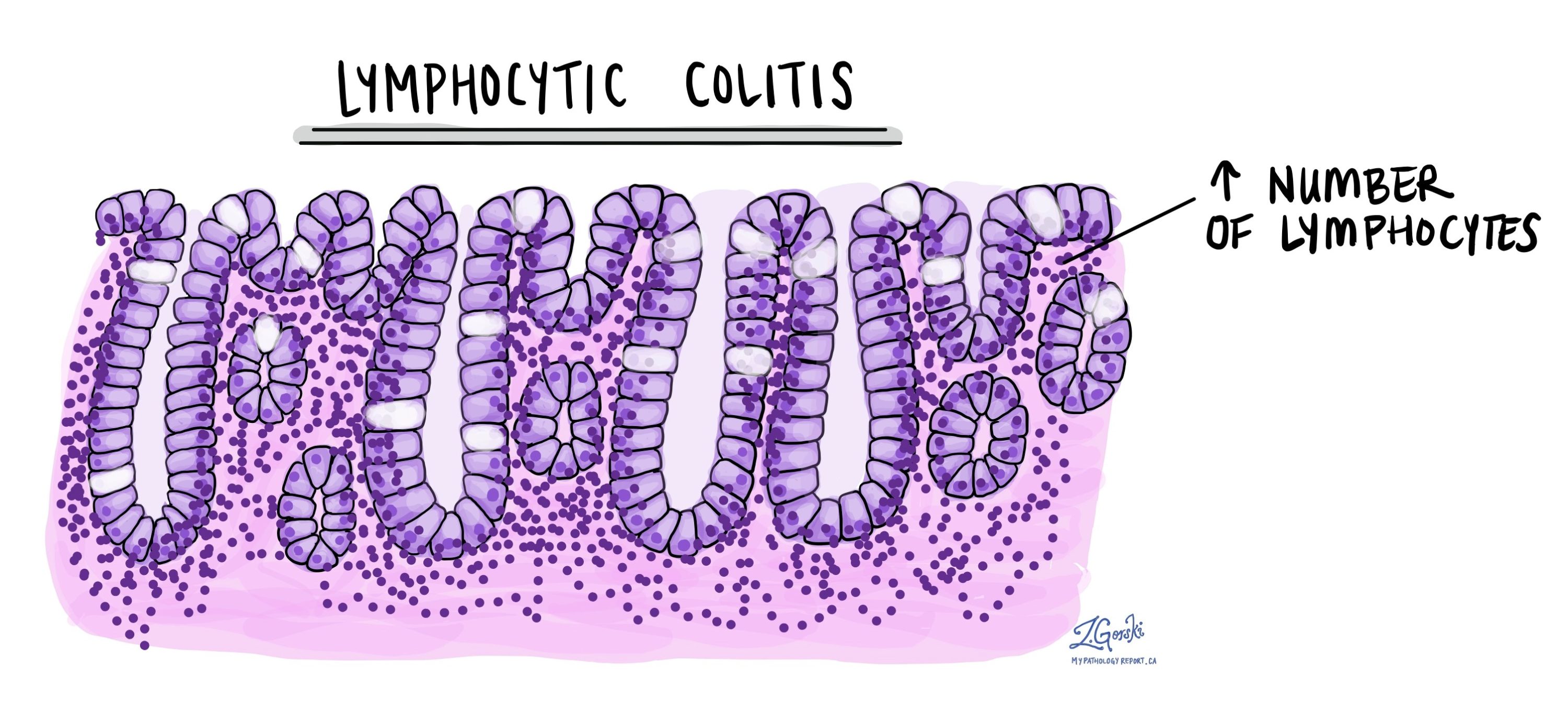

Lymphocytic colitis

In lymphocytic colitis, an increased number of specialized immune cells called lymphocytes are seen within the mucosa on the inside of the colon (which is why the condition is called lymphocytic colitis). These lymphocytes are seen both within the glands and the lamina propria. Pathologists describe this change as intraepithelial lymphocytosis.

Over time, the increased lymphocytes damage the glands. This damage causes the cells to become smaller. Pathologists call this change atrophy. The smaller cells produce less mucin which prevents the colon from functioning normally.

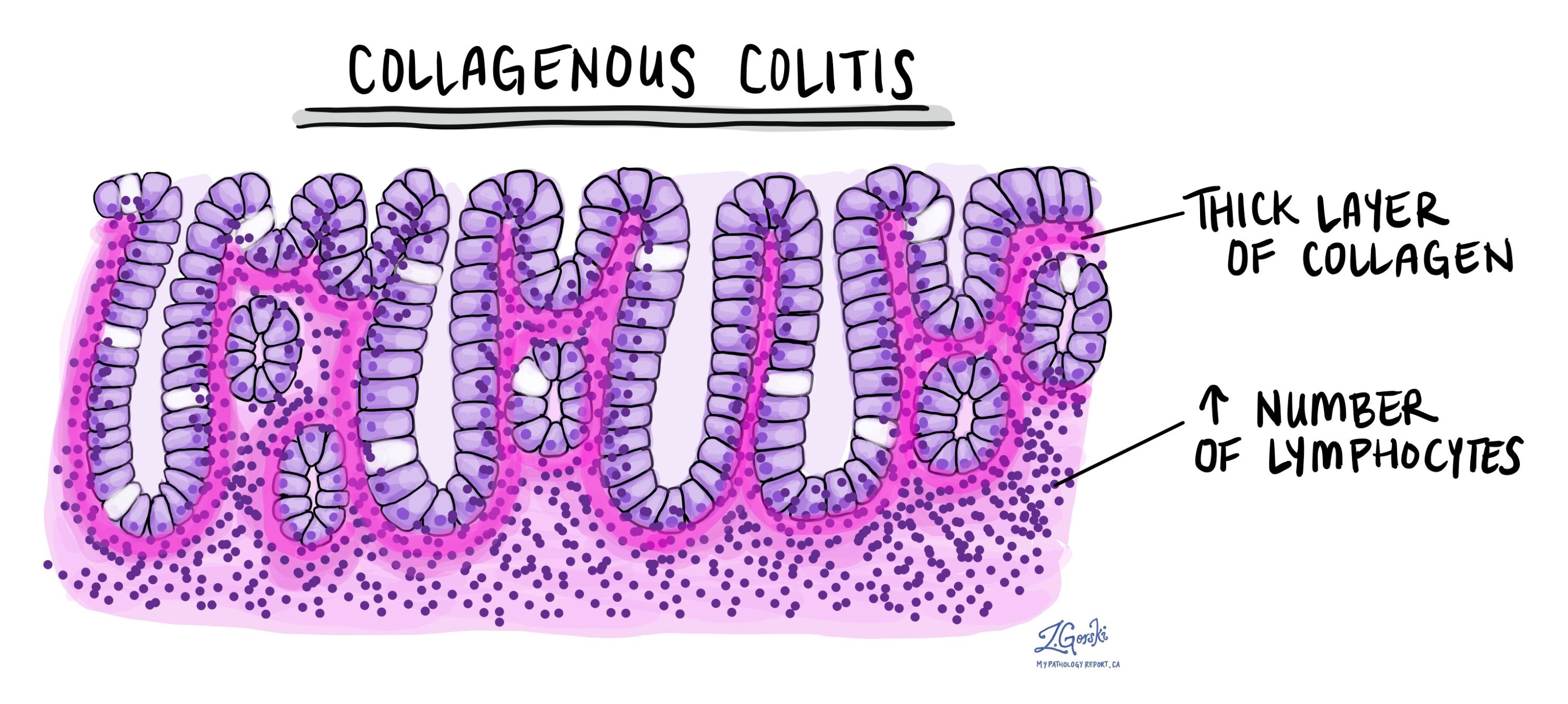

Collagenous colitis

Collagenous colitis shares many features with lymphocytic colitis including an increased number of lymphocytes in the mucosa on the inside of the colon and damaged epithelial cells. In addition, collagenous colitis has an abnormal layer of tissue where the epithelial cells connect with the lamina propria. This thick layer of tissue is made up of a specialized protein called collagen (which is why the condition is called collagenous colitis) and it looks pink when examined under the microscope.

The thick collagen layer traps blood vessels and immune cells near the surface of the epithelium. The extra collagen is believed to be caused by abnormal activity of support cells called myofibroblasts. Some pathologists will perform a special stain called Masson’s trichrome to highlight the collagen band.

While microscopic colitis can cause chronic inflammation in the colon, it is not the same as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). IBD has many features which are not seen in microscopic colitis. For example, the size and shape of the crypts are abnormal. Pathologists call this change crypt distortion. To learn more about the features seen in IBD, read our article on chronic colitis.