by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

August 21, 2023

Myoepithelial carcinoma is a type of salivary gland cancer made up almost entirely of myoepithelial cells. The salivary glands are a group of small organs found predominantly in the head and neck. Most tumours are found in the parotid gland, the largest salivary gland located in the neck just under the ear.

About this article

This article was written by doctors to help you read and understand your pathology report for myoepithelial carcinoma. The sections below describe the results found in most pathology reports, however, all reports are different and results may vary. Contact us if you have any questions about this article or your pathology report. Read this article for a more general introduction to the parts of a typical pathology report.

What causes myoepithelial carcinoma?

At the present time, doctors do not know what causes myoepithelial carcinoma.

What are the symptoms of myoepithelial carcinoma?

Most myoepithelial carcinomas present as a slow-growing, painless mass. More rapid growth may be associated with a tumour arising from a previously benign pleomorphic adenoma.

What does myoepithelial carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma mean?

Myoepithelial carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma means that the malignant (cancerous) myoepithelial carcinoma developed from within a previously benign (noncancerous) tumour called pleomorphic adenoma.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of myoepithelial carcinoma is typically only made after the entire tumour has been removed and sent to a pathologist for examination under the microscope. It is very difficult to distinguish between myoepithelial carcinoma and the similar appearing pleomorphic adenoma in a small tissue sample such as a biopsy or fine needle aspiration (FNA).

What does myoepithelial carcinoma look like under the microscope?

When examined under the microscope, myoepithelial carcinoma is made up of myoepithelial cells that may be described as spindled, epithelioid, plasmacytoid, or clear. The tumour cells are often arranged in groups called nests or nodules which invade (grow into) the surrounding normal salivary gland tissue. A type of connective tissue described as chondromyxoid or myxoid is often seen throughout the tumour. This connective tissue is made by the tumour cells and it gives the tumour a distinctive blue/grey appearance under the microscope. Areas of tumour necrosis (cell death) and mitotic figures (cells dividing to create new cells) may also be seen.

What other tests may be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

Other tests including immunohistochemistry (IHC) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) may be performed to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out other conditions that can look very similar to myoepithelial carcinoma under the microscope. When immunohistochemistry is performed the tumour cells are typically positive for cytokeratin 7 (CK7), S100, SOX10, p63, p40, smooth muscle actin (SMA), and muscle-specific actin. However, not all of these markers will be ordered for every case.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) may be ordered to look for one of the genetic changes or fusions commonly seen in myoepithelial carcinoma of the salivary glands. When NGS is ordered, the results will describe any fusions or other genetic changes identified.

What is lymphovascular invasion and why is it important?

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means that cancerous cells were seen inside a blood or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. The lymphatic vessels connect with small immune organs called lymph nodes that are found throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because cancerous cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other parts of the body such as lymph nodes or the lungs. If lymphovascular invasion is seen, it will be included in your report.

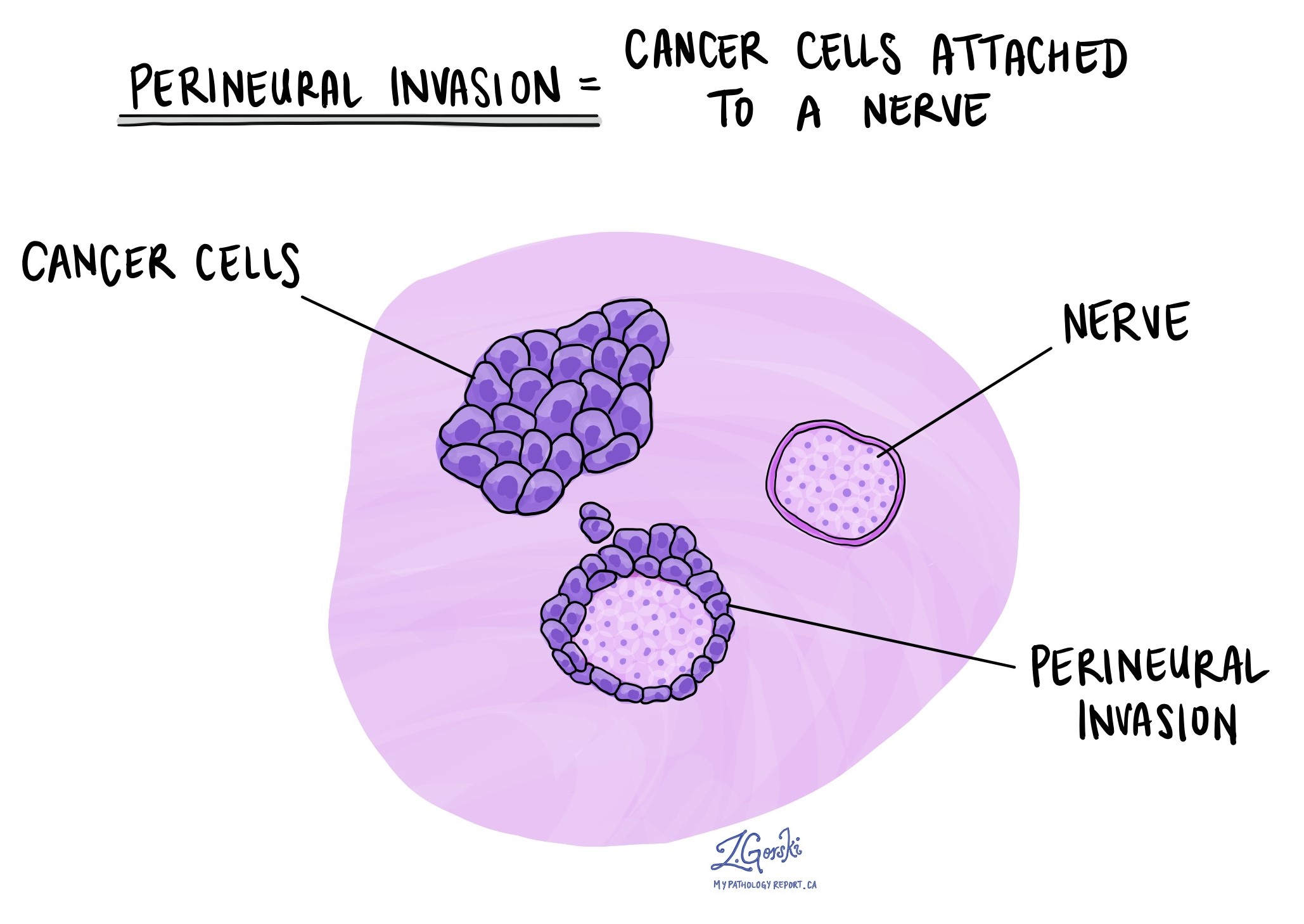

What is perineural invasion and why is it important?

Perineural invasion (PNI) is a term pathologists use to describe cancerous cells attached to or inside a nerve. A similar term, intraneural invasion, is used to describe cancer cells inside a nerve. Nerves are like long wires made up of groups of cells called neurons. Nerves are found all over the body and they are responsible for sending information (such as temperature, pressure, and pain) between your body and your brain. Perineural invasion is important because the cancerous cells can use the nerve to spread into surrounding organs and tissues. This increases the risk that the tumour will regrow after surgery. If perineural invasion is seen, it will be included in your report.

What are lymph nodes and why are they important?

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancerous cells can spread from a tumour to lymph nodes through small vessels called lymphatics. Lymph nodes are not always removed at the same time as the tumour. However, when lymph nodes are removed, they will be examined under a microscope and the results will be described in your report.

Cancerous cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour although lymph nodes far away from the tumour can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are only typically removed if they are enlarged and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancerous cells in the lymph node. Most reports will include the total number of lymph nodes examined, where in the body the lymph nodes were found, and the number (if any) that contain cancerous cells. If cancerous cells were seen in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) will also be included.

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancerous cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancerous cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy is required.

What does it mean if a lymph node is described as positive?

Pathologists often use the term “positive” to describe a lymph node that contains cancerous cells. For example, a lymph node that contains cancerous cells may be called “positive for malignancy” or “positive for metastatic carcinoma”.

What does it mean if a lymph node is described as negative?

Pathologists often use the term “negative” to describe a lymph node that does not contain any cancerous cells. For example, a lymph node that does not contain cancerous cells may be called “negative for malignancy” or “negative for metastatic carcinoma”.

What does extranodal extension mean?

All lymph nodes are surrounded by a thin layer of tissue called a capsule. Extranodal extension means that cancerous cells within the lymph node have broken through the capsule and have spread into the tissue outside of the lymph node. Extranodal extension is important because it increases the risk that the tumour will regrow in the same location after surgery. For some types of cancer, extranodal extension is also a reason to consider additional treatment such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

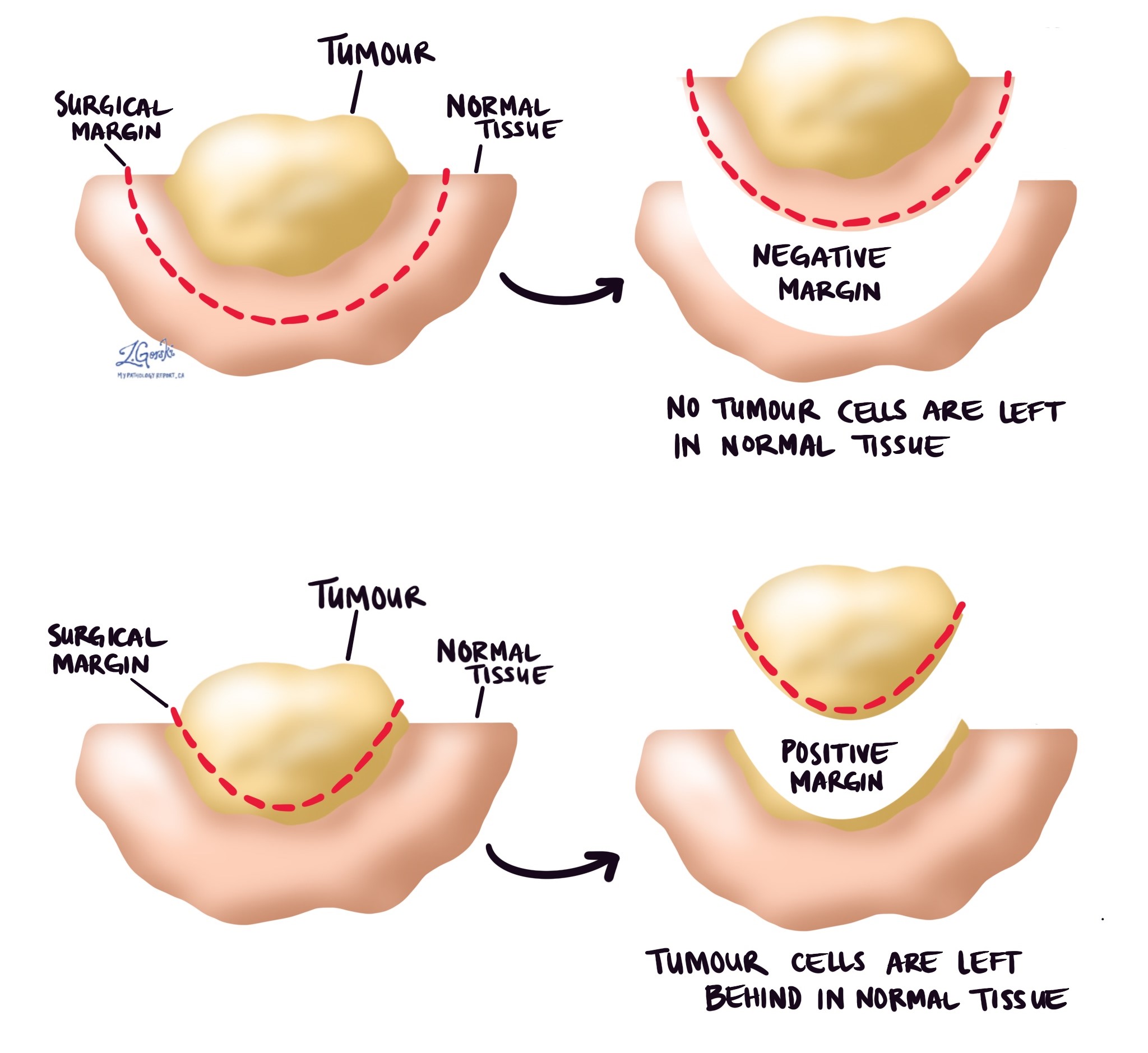

What is a margin and why are margins important?

In pathology, a margin is the edge of a tissue that is cut when removing a tumour from the body. The margins described in a pathology report are very important because they tell you if the entire tumour was removed or if some of the tumour was left behind. The margin status will determine what (if any) additional treatment you may require.

Most pathology reports only describe margins after a surgical procedure called an excision or resection has been performed for the purpose of removing the entire tumour. For this reason, margins are not usually described after a procedure called a biopsy is performed for the purpose of removing only part of the tumour. The number of margins described in a pathology report depends on the types of tissues removed and the location of the tumour. The size of the margin (the amount of normal tissue between the tumour and the cut edge) also depends on the type of tumour being removed and the location of the tumour.

Pathologists carefully examine the margins to look for tumour cells at the cut edge of the tissue. If tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, the margin will be described as positive. If no tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, a margin will be described as negative. Even if all of the margins are negative, some pathology reports will also provide a measurement of the closest tumour cells to the cut edge of the tissue.

A positive (or very close) margin is important because it means that tumour cells may have been left behind in your body when the tumour was surgically removed. For this reason, patients who have a positive margin may be offered another surgery to remove the rest of the tumour or radiation therapy to the area of the body with the positive margin.